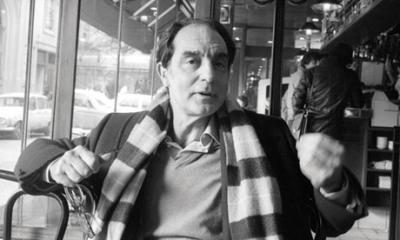

In the summer of 1985, Italo Calvino completed the work to be delivered that autumn for the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard. But on September 6 he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage at his house in Tuscany and died twelve days later at age 62. In the first of these lectures, published in English as Six Memos for the Next Millennium in 1993, he takes up the attribute of “lightness” in literature:

“My working method has more often than not involved the subtraction of weight. I have tried to remove weight, sometimes from people, sometimes from heavenly bodies, sometimes from cities. Above all I have tried to remove weight from the structure of stories and from language … Were I to choose an auspicious image for the new millennium, I would choose that one: the sudden agile leap of the poet-philosopher who raises himself above the weight of the world, showing that with all his gravity he has the secret of lightness, and that what many consider to be the vitality of the times – noisy, aggressive, revving and roaring – belongs to the realm of death, like a cemetery for rusty old cars.“

“My working method has more often than not involved the subtraction of weight. I have tried to remove weight, sometimes from people, sometimes from heavenly bodies, sometimes from cities. Above all I have tried to remove weight from the structure of stories and from language … Were I to choose an auspicious image for the new millennium, I would choose that one: the sudden agile leap of the poet-philosopher who raises himself above the weight of the world, showing that with all his gravity he has the secret of lightness, and that what many consider to be the vitality of the times – noisy, aggressive, revving and roaring – belongs to the realm of death, like a cemetery for rusty old cars.“

In October 1984, Calvino saw the publication of the last collection of essays selected and arranged by him. Collection of Sand (Collezione di sabbia) is finally available in English. But unlike his earlier essays, these pieces do not focus on politics, society and literature. Here, lightness is all. It is as if its manifestation in his nonfiction marked the end of a four decades long transition during which he relinquished all political party affiliation as well as the neorealism of his early novels. Most of these final essays were written in the early 1980’s by which time Calvino had absorbed and refashioned the influence of Roland Barthes, his admired friend and colleague at the Sorbonne. Calvino moved to Paris in 1967.

Collection of Sand comprises four sections. The first part, “Exhibitions – Explorations,” includes ten pieces that mainly deal with shows and exhibits he visited in Paris: an exhibition of “bizarre” collections (sands, cowbells, train-tickets, toilet-paper packaging, etc.), early maps of the New World, the recreation of an 1856 display of wax monstrosities in wax, cuneiform and hieroglyphics, on the making of Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People,” the significance of knots, and famous writers who also drew. Like most of the essays in the collection, these initially appeared in Italian newspapers.

Collection of Sand comprises four sections. The first part, “Exhibitions – Explorations,” includes ten pieces that mainly deal with shows and exhibits he visited in Paris: an exhibition of “bizarre” collections (sands, cowbells, train-tickets, toilet-paper packaging, etc.), early maps of the New World, the recreation of an 1856 display of wax monstrosities in wax, cuneiform and hieroglyphics, on the making of Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People,” the significance of knots, and famous writers who also drew. Like most of the essays in the collection, these initially appeared in Italian newspapers.

The second part, which deals with aspects of the visual, begins with a revealing tribute to Barthes, illuminating the mode of the preceding essays and those to follow. Barthes’ work, he says, “consists in forcing the impersonality of our linguistic and cognitive mechanisms to take account of the physicality of the living and mortal subject … the one who subordinated everything to a rigorous methodology and the one who had just one sure criterion, namely pleasure (the pleasure of intelligence and the intelligence of pleasure.)” Precision and pleasure, phrased through the lightness of speculation, are Calvino’s attributes as well.

One finds these qualities in his essay “The Written City” which looks at the “visible writing” of ancient Rome and medieval cities. After considering examples of protest graffiti in Barthes-mode, he critiques the intrusiveness of some types of graffiti and concludes with a perspective and tone truly his own:

“But have not the poor walls of Italy’s cities also now become a series of layers of arabesques and ideograms and hieroglyphics superimposed on each other, so much so that they no longer transmit any message except that of dissatisfaction with every word and our regret at this wasted energy? Perhaps writing finds a place that is uniquely its own on these walls too, when it refuses to be abused by arrogance and tyranny: a noise which you have to strain your ear carefully and patiently for until you can make out the rare, discreet sound of a word that is for a moment true.”

As its own virtual collection of sand, these essays represent a cerebral “collecting that restores unity and a sense of the whole that is homogenous with the dispersal of things … the recognizing of oneself in the object” – though here he is discussing the writings of art and literature critic Mario Praz.

As its own virtual collection of sand, these essays represent a cerebral “collecting that restores unity and a sense of the whole that is homogenous with the dispersal of things … the recognizing of oneself in the object” – though here he is discussing the writings of art and literature critic Mario Praz.

The third part, “Accounts of the Fantastic,” includes reviews that cover Scottish fairy mythology, eighteenth century automata created by clockmakers, and an encyclopedia of imaginary places. The artist Donald Evans, who designed postage stamps of dreamed-up countries, is portrayed as having “the nostalgic vision of the stamp album [which] allowed him to cultivate an interiority that had at the same time become objectivized and dominated by his consciousness,” a mode with much in common with Calvino and his Invisible Cities.

The final section includes travel essays on Japan, Mexico and Iran. In the Japanese garden, he finds a model for his art: “The construction of a nature that can be mastered by the mind so that the mind can in turn receive a sense of rhythm and proportion from nature: that is how one could define the intention that has led to the layout of these gardens. Everything here has to seem spontaneous and for that reason everything is calculated.” Of the Japanese house, he writes, “It is by limiting the number of things around us that one prepares oneself for accepting the idea of a world that is infinitely larger than ours.” The precision of his essays’ phrasing, so intent on reaching the seen object, selects its words with spareness to acknowledge everything beyond.

The final section includes travel essays on Japan, Mexico and Iran. In the Japanese garden, he finds a model for his art: “The construction of a nature that can be mastered by the mind so that the mind can in turn receive a sense of rhythm and proportion from nature: that is how one could define the intention that has led to the layout of these gardens. Everything here has to seem spontaneous and for that reason everything is calculated.” Of the Japanese house, he writes, “It is by limiting the number of things around us that one prepares oneself for accepting the idea of a world that is infinitely larger than ours.” The precision of his essays’ phrasing, so intent on reaching the seen object, selects its words with spareness to acknowledge everything beyond.

The essays have an enveloping lightness because, unlike most work in this genre, they do not reflect credit on their own perceptive powers. Calvino says, “The true artist does not love or respect his material: it is always ‘on trial’ and everything can go completely wrong.” Lightness is an attribute of writing that, as Giorgio Agamben commented, “maintains its contact with the mythical origin of the word.” Speaking of Lucretius in his Norton lectures, Calvino said, “Lightness of thoughtfulness … issues from a poet who had no doubt whatever about the physical reality of the world.” His final essays are exquisite blends of lightness and physicality, and also humility: the attempt to recover those mythical origins is an endless effort. Through an attention to what is singular and unique, he finds “revelatory clues” of those sources. The essays express Calvino’s loyalty to the necessity of searching for them.

[Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt/Mariner Books on September 16, 2014. 240 pages, $13.95 paperback. Mariner Books has also published Calvino’s Into The War, containing three of his early stories, and The Complete Cosmicomics.]