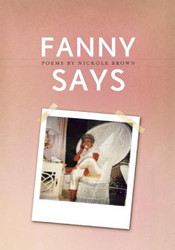

The title character of Fanny Says, Nickole Brown’s second collection, is her late grandmother, Frances Lee Cox of Bowling Green, Kentucky. “What people don’t know about my name / is that my grandmother gave me that ‘k’ – my very own unexpected consonant,” she writes in “Fanny Linguistics: Nickole.” Although the poems illuminate Fanny’s life and behavior, Fanny Says is an acknowledgement and appreciation of an inheritance, the poet’s striving “to keep alive a fierce and singular part of myself that lives only through her,” as Brown remarked in an interview.

Fanny Says is animated by the elemental principles of presence — the unique habits of an individual and the flaring of its influence through language. Confucius taught that our essences are the same — we differ only in our habits. And this leads to Brown’s impetus: if our lives matter it’s because our differences matter. But Brown isn’t a sentimentalist nor does she dismiss ambiguity for some muzzy unifying principle. What Fanny says and how she says it are paramount here.

Fanny Says is animated by the elemental principles of presence — the unique habits of an individual and the flaring of its influence through language. Confucius taught that our essences are the same — we differ only in our habits. And this leads to Brown’s impetus: if our lives matter it’s because our differences matter. But Brown isn’t a sentimentalist nor does she dismiss ambiguity for some muzzy unifying principle. What Fanny says and how she says it are paramount here.

In “Fuck,” the opening poem, Brown swiftly introduces us to her. “Fuck” is the word that triggers a world – just as a word creates the world on the first page of the Bible. Here are the poem’s first two stanzas:

is what she said, but what mattered was the tone –

not a drive-by spondee and never the fricative

connotation as verb, but from her mouth

voweled, often preceded by well, with the “u” low

as if dipping up homemade ice cream, waiting to be served

last so she’d scoop the fruit from the bottom, where

all the good stuff had settled down.

Imagine: not a word cold-cocked or screwed to the wall

but something almost resigned – a sigh, an oh, well

the f-word made so fat and slow it was basset hound,

chunky with an extra syllable, just enough weight

to make a jab to the ribs more of a shoulder shrug.

Think of what’s done to “shit” in the South; this is

shee-aaatt but flicked with a whip, made a little more

tart. Well, fuck, Betty Sue, I never did see that coming.

Can you believe?

The granddaughter honors the matriarch not through emulation but observation immune to the typical acids of generational judgment. The child learned early to exert her own self by being one’s own difference among differences. As one of the poems’ governing co-presences, she underscores her own interests – sound, tone, story, and the habits of honest work with words.

The granddaughter respects her own memories by recognizing them as preserved fragments. Converted into language for the telling, each piece assumes its own shape. Richly conceived, Fanny Says is dense with material yet welcoming in its spirited shape-shifting. It is cross-genre with a purpose. There are lyric narratives, sequences, prose poems, and monologues in Fanny’s voice that are sometimes presented as instructions (“Fanny Says How to Tend Babies”: “1. When expecting, you can smoke and tan and dye your hair, but don’t you go reaching up on the clothesline: believe you me, Barbara lost Charlie the minute she reached up on the clothesline …”).

The granddaughter respects her own memories by recognizing them as preserved fragments. Converted into language for the telling, each piece assumes its own shape. Richly conceived, Fanny Says is dense with material yet welcoming in its spirited shape-shifting. It is cross-genre with a purpose. There are lyric narratives, sequences, prose poems, and monologues in Fanny’s voice that are sometimes presented as instructions (“Fanny Says How to Tend Babies”: “1. When expecting, you can smoke and tan and dye your hair, but don’t you go reaching up on the clothesline: believe you me, Barbara lost Charlie the minute she reached up on the clothesline …”).

At mid-book comes “A Genealogy of the Word,” Brown’s unflinching and challenging sequence on Fanny’s and the culture’s attitude toward race. It begins with a jab: “Saying ‘the n-word’ is a cop-out, robbing / history of its essential / grit, faked out …” A black woman named Bernie May “came to the house regular / as the mail” to clean house and cook:

Sometimes, Bernie’d stop long enough to set up

the joke, asking, Mrs. Cox, now say again

what would you do if your blonde grandchild here

fell in love with a black man

like my cousin Tyrone?

Fanny’d reach into her roller bowl, pull out her gun.

She’d point it at my face.

If she was with a nigger man, I’d have to kill her.

A purdy girl like her can’t get a white man?

Then Fanny’d put the gun

down, and they’d both laugh

and laugh.

Half the fun for them was to see me

jump off the couch and stomp down

the hall, but what they didn’t know

was I knew Fanny’d never hurt me,

no. It was never the gun that made me

flinch.

The reader flinches here, too, of course – but Brown won’t relent. Affection and care swirl among vulgarities and crassness. But Fanny “was loyal – downright militant – to things she loved, Pepsi was all // she would drink. Rarely water, not juice, not milk, and damn straight, no trailer-trash beer.” Fanny with her gallstones, Fanny betrayed by her husband.

Nickole Brown (nicknamed “Koey” by Fanny) began in 1992 to keep notebooks about Fanny, filling the pages with her grandmother’s stories. Although Fanny Says has the authority of documentary, its presence comprises something both more grand and strange – a mind simultaneously borrowing and separating from its sources. It was Fanny who told the story about her first period, her “monthly,” so that even now the granddaughter asks for “A word, please, somebody give me, for that season with her uterus // small and tight as an inedible green pear, her body keening and cramped in its stall.”

Nickole Brown (nicknamed “Koey” by Fanny) began in 1992 to keep notebooks about Fanny, filling the pages with her grandmother’s stories. Although Fanny Says has the authority of documentary, its presence comprises something both more grand and strange – a mind simultaneously borrowing and separating from its sources. It was Fanny who told the story about her first period, her “monthly,” so that even now the granddaughter asks for “A word, please, somebody give me, for that season with her uterus // small and tight as an inedible green pear, her body keening and cramped in its stall.”

There are experiences that the granddaughter in turn would have liked Fanny to appreciate and connect with. Now, it’s up to the reader to provide that recognition. The lines below conclude “An Invitation for My Grandmother,” now deceased:

And three years ago: Can I take you there?

My sister, sitting up during a contraction, how she reached inside

herself to touch the crown of her son

not yet born. I want to show you the look

on her face and that cord

cut, a rich earth of blood, a thick black

joy. And please, take off your shoes now,

stand with me last October when

I took a wife, barefoot in the grass.

We made our vows, and after, when she held

my jaw with both hands, I could feel

the bones of my skull

rising up to make a face finally

seen.

[Published by BOA Editions on April 10, 2015. 148 pages, $16.00 paperback]