The essential facts of Edward Limonov’s life are spelled out on the cover of Emmanuel Carrère’s book: He is born Edward Savenko in Dzerzhinsk, Ukraine in 1943 just as twenty million Russians die at the hands of the Germans. Stalin is the savior of those who survive. His father is a low-level NKVD official. A teenage thug-wannabe with a bohemian attitude, he goes to Moscow where he lives an indigent and semi-notorious life as a Soviet poet.

In 1975, he emigrates to New York City with his attractive wife, expecting never to return. She fails to find work as a model and leaves him; he writes his first novel, the scandalous It’s Me, Eddie, considered by Lawrence Ferlinghetti for City Lights but ultimately published in Paris in 1983 (he moves there in 1980). Now also with Grove Press, he publishes His Butler’s Story (1987) and Memoirs of a Russian Punk (1990). In Paris, he polishes his affect as a Russo-punk, decrying all forms of political correctness and mocking Gorbachev.

In 1975, he emigrates to New York City with his attractive wife, expecting never to return. She fails to find work as a model and leaves him; he writes his first novel, the scandalous It’s Me, Eddie, considered by Lawrence Ferlinghetti for City Lights but ultimately published in Paris in 1983 (he moves there in 1980). Now also with Grove Press, he publishes His Butler’s Story (1987) and Memoirs of a Russian Punk (1990). In Paris, he polishes his affect as a Russo-punk, decrying all forms of political correctness and mocking Gorbachev.

At this point, he has been away from Russia for fifteen years. He returns at the end of 1989 with a vision of himself as the country’s next leader. He goes to the Balkans where a BBC documentarian films him alongside Serbian fighters and discharging a rifle towards Sarajevo (later he claims he was aiming at a firing range, but one never knows with Limonov). In Russia, he establishes the National Bolshevik Party, a 10,000-member group comprising young malcontents and drop-outs, fringe artists and musicians, hoodlums and neo-Fascist skinheads, all willing to risk voicing their dissatisfactions. The Party’s platform is a mash-up of power worship, occult Nazism, homesickness for the U.S.S.R., and anarchy. In 2001 at age 58, he is arrested, tried, given a four-year sentence and sent to prison for attempting to foment an uprising of Russian nationals in Kazakhstan. In jail he writes four more books.

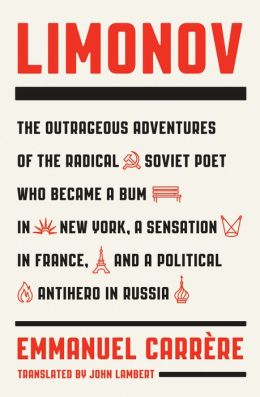

Knowing the biographical facts in no way diminishes one’s enjoyment of Carrère’s Limonov which was a best-seller in France in 2011. The copy on the cover flap of Limonov describes the contents as a “pseudobiography,” a signal that the author has intruded on his subject in some fashion. But this engaging narrative comprises something different and harder to define than the usual pivot between biography and memoir. Carrère seems to have ingested his subject. In his 2010 memoir, My Life as a Russian Novel, Carrère begins with a narrative about traveling to a rural Russian town to investigate the case of a Hungarian soldier who had been imprisoned since 1944 – but soon arrives at its true subject, namely himself and a family secret concerning Nazi collaboration. In Limonov, the urge to self-inscribe is more lurid, disquieting and suggestive.

Knowing the biographical facts in no way diminishes one’s enjoyment of Carrère’s Limonov which was a best-seller in France in 2011. The copy on the cover flap of Limonov describes the contents as a “pseudobiography,” a signal that the author has intruded on his subject in some fashion. But this engaging narrative comprises something different and harder to define than the usual pivot between biography and memoir. Carrère seems to have ingested his subject. In his 2010 memoir, My Life as a Russian Novel, Carrère begins with a narrative about traveling to a rural Russian town to investigate the case of a Hungarian soldier who had been imprisoned since 1944 – but soon arrives at its true subject, namely himself and a family secret concerning Nazi collaboration. In Limonov, the urge to self-inscribe is more lurid, disquieting and suggestive.

When Limonov served his time in a labor camp, he noticed that the sinks, “made of a polished steel plate above a cast iron pipe with sober, pure lines, are exactly the same as in a hotel conceived by the designer Philippe Starck, where Limonov’s American publisher put him up the last time he visited New York … He wondered if many people in the world apart from him had lived such different lives … No, he concluded, probably not. That was a source of pride for him, a pride that I can understand. The gap between those two lives he’s lived is what made me want to write this book.”

Carrère-as-narrator mainly inhabits the gap, often slipping into a voice that could be Limonov’s, adopting his manner and prejudices, even at times his nihilism. He describes Limonov as a groovy amalgam of Lou Reed, Michel Houellebecq and Daniel Cohn-Bendit. Carrère never quite says that Limonov’s writing is any good, but he does admire its attitude. (Knowing that he is a more sophisticated writer than Limonov is his unstated source of pride and comfort, made obvious by an effort to understate his own popularity and achievements.) In New York, Limonov was embraced by the beau monde as a Ukrainian émigré, lived in a halfway house, had sex with a homeless man in a park, worked as a butler, and wrote more prose …

Carrère-as-narrator mainly inhabits the gap, often slipping into a voice that could be Limonov’s, adopting his manner and prejudices, even at times his nihilism. He describes Limonov as a groovy amalgam of Lou Reed, Michel Houellebecq and Daniel Cohn-Bendit. Carrère never quite says that Limonov’s writing is any good, but he does admire its attitude. (Knowing that he is a more sophisticated writer than Limonov is his unstated source of pride and comfort, made obvious by an effort to understate his own popularity and achievements.) In New York, Limonov was embraced by the beau monde as a Ukrainian émigré, lived in a halfway house, had sex with a homeless man in a park, worked as a butler, and wrote more prose …

“Not poems or a story this time, but short prose pieces, rarely longer than a page, in which he jots down everything he’s got in his head. What he’s got in his head is ghastly, but you’ve got to admire the honesty with which he unloads it: resentment, envy, class hatred, sadistic fantasies, but no hypocrisy, no embarrassment, no excuses. Later this will become a book, one of his best in my mind, Diary of a Loser.”

Carrère also reveals that Limonov had once sent a copy of his novel, The Russian Poet Prefers Big Blacks, to his famous mother, Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, author of the prescient Decline of an Empire. He recalls, “The more I read, the more I felt that I was made of dull and mediocre stuff, and that I was doomed in this world to play the role of walk-on, and a bitter, envious walk-on at that … because he lacks charisma, generosity, courage – that he lacks everything, in fact, but the horrible lucidity of the loser.”

Referring to Limonov as his book’s “hero,” Carrère entices the reader to lean in and regard his subject as worthy of our respect, even our empathy. In the process, he knowingly skirts the edges of fascism, regarding Limonov as an example of how one man in a cruel world deals directly with brutality: “I’m not talking about neo-Nazis or the extermination of presumed inferiors … but about the way each of us deals with the evident fact that life is unjust and people are unequal: more or less beautiful, more or less talented, more or less prepared for the fight. Nietzsche, Limonov, and this extreme moral stance within us that I’m calling fascist say with one voice: ‘That’s reality, that’s the world as it is.’ What else can you say? What stands against this basic fact?”

Watching Carrère debase himself — or pretend to — is the spectacle here and it is truly entertaining to observe. His story’s quick pace (which creates the illusion of the collapse of eras into a single zone of blunt human truth, from Stalin to the Cold War to Perestroika) and his familiar tone fraternize with those of us who may hesitate to consider unbounded self-pity, inflated self-regard, a harsh ignorance of women, odium for fellow writers (Limonov detested Joseph Brodsky for his fame), and a talent for exploitative writing as characteristics of a hero. Carrère insists that Limonov “is neither vile nor a liar”; he has spent time with his subject and wields the Buddhist sutra that “a man who judges himself superior, inferior, or even equal to another does not understand reality.” But Limonov certainly makes such judgments, and so does Carrère as his self-assessments (perhaps engineered for this book?) plainly state.

Watching Carrère debase himself — or pretend to — is the spectacle here and it is truly entertaining to observe. His story’s quick pace (which creates the illusion of the collapse of eras into a single zone of blunt human truth, from Stalin to the Cold War to Perestroika) and his familiar tone fraternize with those of us who may hesitate to consider unbounded self-pity, inflated self-regard, a harsh ignorance of women, odium for fellow writers (Limonov detested Joseph Brodsky for his fame), and a talent for exploitative writing as characteristics of a hero. Carrère insists that Limonov “is neither vile nor a liar”; he has spent time with his subject and wields the Buddhist sutra that “a man who judges himself superior, inferior, or even equal to another does not understand reality.” But Limonov certainly makes such judgments, and so does Carrère as his self-assessments (perhaps engineered for this book?) plainly state.

Nevertheless, the story of how Limonov evolved from a Ukrainian ruffian to a thorn in Putin’s side is riveting as Carrère tells it. Moreover, the final chapters on the Yeltsin era and the entrenchment of Putin illuminate current events in the Ukraine and Crimea, the assassination of journalist Anna Politskaya, and the prosecution of Pussy Riot. Limonov’s National Bolshevik Party (whose flag incorporates the red background/white circle of Hitler’s flag with the hammer and sickle) now seeks “a pacifist, democratic revolution, which is what the Kremlin fears above all else and will stop at nothing to crush.” But Limonov is not a dissident like Solzhenitsyn or Sakharov, both of whom he sneers at. He is a delinquent; that is his brand. Perhaps he is mellowing: in 2006 he married the well-known Russian actress Ekaterina Volkova; they have two children. He claims to enjoy cooking and sewing (he once made and sold jeans in 1970’s Moscow).

Nevertheless, the story of how Limonov evolved from a Ukrainian ruffian to a thorn in Putin’s side is riveting as Carrère tells it. Moreover, the final chapters on the Yeltsin era and the entrenchment of Putin illuminate current events in the Ukraine and Crimea, the assassination of journalist Anna Politskaya, and the prosecution of Pussy Riot. Limonov’s National Bolshevik Party (whose flag incorporates the red background/white circle of Hitler’s flag with the hammer and sickle) now seeks “a pacifist, democratic revolution, which is what the Kremlin fears above all else and will stop at nothing to crush.” But Limonov is not a dissident like Solzhenitsyn or Sakharov, both of whom he sneers at. He is a delinquent; that is his brand. Perhaps he is mellowing: in 2006 he married the well-known Russian actress Ekaterina Volkova; they have two children. He claims to enjoy cooking and sewing (he once made and sold jeans in 1970’s Moscow).

The violence of his imagination, as opposed to his acts, suggests that he may have more in common with Celine than with Trotsky (whom he strives to resemble). In his 2003 book The Other Russia, he proposed to solve the decrease in population by forcing every woman between 25 and 35 to have four children who would be taught by the state “to shoot grenade launchers, jump from helicopters, besiege cities, skin sheep and pigs, cook good hot food, and write poetry … Many types of people will have to disappear.” Asked to explain this plan, he said, “Fuck! I forgot I wrote that. I feel free to use dreams in my work … It’s a different genre from my politics. It’s not dogma.” (This was reported in The Observer.)

Mikhail Shishkin, dubbed by some Western critics as Russia’s greatest novelist, refused to attend the 2013 U.S. Book Expo because he did not want to represent a country where “power has been seized by a corrupt, criminal regime” run by “a pyramid of thieves.” I quote from his dissenting letter, mailed in from Zurich where he has lived since 1995, to Russia’s Federal Agency for Press and Mass Communications. Limonov responded on his blog: “So he is barking from Switzerland. Yes, my dear, Russia is a shameful paternalistic medieval state. But you have no right to say anything from the safety of Switzerland” (translation via Masha Gessen of the New York Times). Limonov, who has recently been beaten with bats and narrowly escaped assassination, demands and gets points for shouting: stand up and fight!

[Published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux on October 21, 2014. 340 pages, $30.00 hardcover]

Limonov

The author states that Limonov indicates something important about Putin World. But the book has just as much to say (if not more) about French public intellectuals. In a vicarious manner, Emmanuel Carrère has committed an act of ersatz transgression: the violation of literary form. This is the best the French can do now, as even he seems to admit. But I agree that this is a very entertaining book. Anyone who feels cramped by the constant effort of political correctness will respond to the book’s attitude and rhythm. Anyone who is the least bit cynical about American or French politics will admire Limonov’s brashness. That is, if you can believe Carrère’s version of Limonov. Carrère says the book is part fiction. Which parts? This is his little sin. Maman made a famous book according to conventional standards of research. Le fils wants to be congratulated for making poo-poo in his pants.

The real Eduard Limonov

Hello Ron , excellent commentary on the book of Carrère . The real Eduard Limonov is even more extraordinary than tells Emmanuel Carrère , who made a lot of mistakes and misinterpretations .

Today , in Russia, Eduard Limonov is considered a model by the most famous Russian young writers (Prilepin , Shargunov , Sentchine , Sadoulaev , etc …).

Limonov , now in Russia is not considered a fascist (!), but as the leader of the radical left-wing opposition , the ultra left anti- system opposition.

At the time of the translation of the Book of Emmanuel Carrère in Russia, all these errors were noted by commentators objectives .

Limonov has written eight books, not four during his two and a half years in prison from 2001 to 2003.

“Le poète russe préfère les grands négres” (The Russian Poet Prefers Big Blacks)was published in France in 1980 (I have the original edition).The English translation , “It’s Me Eddie” , dates from 1983.

All this and much more is on my website TOUT SUR LIMONOV.

There are a lot of new information about the real Eduard Limonov , photos and videos hard to find.

The presentation page is in French, very easy to understand with Google Trad .

There are also twenty pages in English :

http://www.tout-sur-limonov.fr/