Two days after his mother died in October, 1977, Roland Barthes wrote on a slip of paper, “Everyone guesses – I feel this – the degree of a bereavement’s intensity. But it’s impossible (meaningless, contradictory signs) to measure how much someone is afflicted.” The unstated question provoking his fragmentary responses is: What form does my grieving take? A year later, he was still struggling: “– liquidate without interruption what prevents me, separates me from writing the text about maman: the active departure of Suffering: accession of Suffering to the Active position.” Ultimately, the text arose in the form of Camera Lucida – but not before Barthes picked apart his unrelenting grief and conflicting emotions. The recently published Mourning Diary entries are exclamations, admissions and moans.

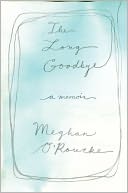

Meghan O’Rourke’s mother, Barbara Jean Kelly O’Rourke, died at age 55 on Christmas day, 2008, of colorectal cancer. Her daughter’s new memoir, The Long Goodbye, expresses an inveterate anxiety similar to Barthes’, the frantic held in check. Like Barthes’ notes, The Long Goodbye is hardly a memoir at all, since O’Rourke has not had time to remember her grief, only to grope for a form in which to conceive of it.

Meghan O’Rourke’s mother, Barbara Jean Kelly O’Rourke, died at age 55 on Christmas day, 2008, of colorectal cancer. Her daughter’s new memoir, The Long Goodbye, expresses an inveterate anxiety similar to Barthes’, the frantic held in check. Like Barthes’ notes, The Long Goodbye is hardly a memoir at all, since O’Rourke has not had time to remember her grief, only to grope for a form in which to conceive of it.

Memoirs-of-adversity are almost always about coming to terms, of having emerged whole, appreciative, addressing the reader from a still point of rumination and recall. But The Long Goodbye has been written on choppy waters. There is little consolation in it. She has learned from the literature of mourning that “its solace lies in the ritual of remembering the dead and then saying, There is no solace and also, This has been going on a long time.”

In the narrative’s details, she is generally more invested in embodiment than argument. But in its emotional foundation, the book is contentious and even petulant. At the outset, she critiques the culture: “What does it mean to grieve when we have so few rituals for observing and externalizing loss?” She envies “my Jewish friends the practice of saying Kaddish.” She punctures the relevance of the “five stages of grief” popularized by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. In short, she takes us down to the baseline of grief. Throughout The Long Goodbye, O’Rourke introduces us to people who fail to gauge or participate in her suffering – her husband (they divorce), healthcare staff, passing acquaintances. The ones who would prefer that the griever “get over it.” An overriding purpose of The Long Goodbye is to convert us into an attuned, responsive, respectful audience.

O’Rourke’s portrayal of her family is the gateway to the unsettled and conflicting moments that so affectingly portray the tense, desperate and unresolved nature of her grief. The pending death of a parent revives one’s specific identity as that person’s child. Of her mother O’Rourke writes, “She had always been my protector: whenever something went wrong, she was the one I looked to for help. But we’d never had the kind of relationship that involved talking every day or sharing every detail of our lives … we had lost some of the ease and physical closeness.” The lore of her mother’s life forms a kind of mythic image of a dynamic female: “I was, as a child, already nostalgic for her youth … I’d sometimes pretend that I had her life.” The mother “is a pragmatist to the core.” The child “was nervous and my mother wasn’t … my mother and I were profoundly different from each other.”

O’Rourke’s portrayal of her family is the gateway to the unsettled and conflicting moments that so affectingly portray the tense, desperate and unresolved nature of her grief. The pending death of a parent revives one’s specific identity as that person’s child. Of her mother O’Rourke writes, “She had always been my protector: whenever something went wrong, she was the one I looked to for help. But we’d never had the kind of relationship that involved talking every day or sharing every detail of our lives … we had lost some of the ease and physical closeness.” The lore of her mother’s life forms a kind of mythic image of a dynamic female: “I was, as a child, already nostalgic for her youth … I’d sometimes pretend that I had her life.” The mother “is a pragmatist to the core.” The child “was nervous and my mother wasn’t … my mother and I were profoundly different from each other.”

By page 40, the cancer has metastasized and death is certain; the mother calls O’Rourke who is waiting in the anteroom of a spa for a massage:

“ ‘I am so sorry,’ I said. I sank down on the porch steps, having gotten outside somehow, away from the flowers. But my ‘sorry’ felt a bit like a lie. Did I want my mother to die? No, I did not want my mother to die. But I couldn’t stand the pain and sickness. And I couldn’t stand trying to comfort her. Mainly, I was in disbelief. I couldn’t feel a thing yet – not even sorrow.”

Assuming the unaccustomed role of caregiver, she worries that her mother “resented my constant fussing … I wanted to have an unburdening conversation with her. Some part of me was still angry she hadn’t been unquestionably on my side during the divorce.” Frenetic, shaken, and scared, O’Rourke-as-character captures the gut-ache of living “with a daily foreboding.” But there is also anger, the making of demands, estrangement and self-protection.

In a scene at her parents’ house, Barbara shuffles to the garage to clean bird shit off her car after asking Meg to handle the task. “ ‘I am cleaning the bird shit off the car,’ she said acerbically. She meant clearly: You are favored no more, my daughter. … She came back into the house. ‘Are you upset with me?’ she said. ‘Are you upset about something?’ “

Then comes this passage:

“When I got angry as a kid I would hide in my bedroom and get under my quilt and cry until I was too hot and sweaty to stay under it anymore. The quilt was yellow, patterned with dark yellow butterflies. The light around me would be golden and gorgeous and redolent of my grief and wronged status. Finally, when I had wept myself out, I would emerge. Now I wanted to do the same. Instead I said, ‘Yes, I’m upset. I haven’t seen you. I had a horrible, hard week, it’s Thanksgiving, and the first thing you do is scold me about the bird shit. ‘ … Inside me, some last plank of steadiness broke. There was nothing motherly about her. The mother would have noticed my desperation …”

“When I got angry as a kid I would hide in my bedroom and get under my quilt and cry until I was too hot and sweaty to stay under it anymore. The quilt was yellow, patterned with dark yellow butterflies. The light around me would be golden and gorgeous and redolent of my grief and wronged status. Finally, when I had wept myself out, I would emerge. Now I wanted to do the same. Instead I said, ‘Yes, I’m upset. I haven’t seen you. I had a horrible, hard week, it’s Thanksgiving, and the first thing you do is scold me about the bird shit. ‘ … Inside me, some last plank of steadiness broke. There was nothing motherly about her. The mother would have noticed my desperation …”

These emotional tangles give The Long Goodbye its credible attitude and compelling authenticity – and lead to O’Rourke’s points about the protean shapes of grief as well as its “permanently transitional quality.”

Barthes wrote, “In taking these notes, I’m trusting myself to the banality that is in me.” O’Rourke has been just as unsuspicious. As a poet, O’Rourke produces verse with a lively, sometimes biting lyricism. There is little lyricism in The Long Goodbye but she does flash her incisors from time to time. She evokes her mother’s bluntness – yet also speaks to the bulging, conventional sweet spot of the memoir market.

But The Long Goodbye does not indulge in the typical, annoying memoirist’s habits of being too plausible or denying exceptional status while building a case for it. In a fine passage on Hamlet, she notes how much of the play “is about the precise kind of slippage the mourner experiences … the sense that one is expected to perform grief palatably.” The Long Goodbye is a fine slippage into distressed acknowledgement.

But The Long Goodbye does not indulge in the typical, annoying memoirist’s habits of being too plausible or denying exceptional status while building a case for it. In a fine passage on Hamlet, she notes how much of the play “is about the precise kind of slippage the mourner experiences … the sense that one is expected to perform grief palatably.” The Long Goodbye is a fine slippage into distressed acknowledgement.

[Published by Riverhead Books on April 14, 2011. 320 pages, $25.95 hardcover]

distressed acknowledgement

“a fine slippage into distressed acknowledgment.” The very phrase is like a bell

that summons me to read the bleedin’ book — well, one of these days. The primary role (the author’s) seems crisply visible, right here in the review.