Rawi Hage’s Beirut Hellfire Society opens with a prologue in which sixteen-year-old Pavlov is inducted by his father into the Hellfire Society, a clandestine group that arranges the disposition of dead people who have been denied conventional burial.

This premise grabbed me for reasons more heartfelt than literary. Several years ago, I went to an island off the coast of Africa to repatriate to the U.S. my father’s then-still-living but stroke-disabled body. My family knows too well the arduous griefs in resorting to unconventional means to take care of a beloved body that can’t take care of itself.

As the narrative opens, Pavlov is twenty. By day, his father plies the conventional side of his trade as undertaker, arranging funerals and burying the dead in the cemetery visible from the family home. He practices his true vocation as a member of “the mysterious Society that was somehow connected with fire.” The Society, which for all Pavlov knows comprises only his father and himself, cremates the dead in an obscure, small stone house in the mountains, sending them into the flames with a dance, a drink of whiskey, an arcane jumble of ancient myth and prayer sung and recited. Pavlov fully inherits the vocation after his father is killed by a bomb that tumbles pieces of his body into a grave he was digging, the undeniable irony of which sets certain neighbors gloating.

As the narrative opens, Pavlov is twenty. By day, his father plies the conventional side of his trade as undertaker, arranging funerals and burying the dead in the cemetery visible from the family home. He practices his true vocation as a member of “the mysterious Society that was somehow connected with fire.” The Society, which for all Pavlov knows comprises only his father and himself, cremates the dead in an obscure, small stone house in the mountains, sending them into the flames with a dance, a drink of whiskey, an arcane jumble of ancient myth and prayer sung and recited. Pavlov fully inherits the vocation after his father is killed by a bomb that tumbles pieces of his body into a grave he was digging, the undeniable irony of which sets certain neighbors gloating.

As I began to read the book, I thought, perhaps I won’t understand this after all. I’ve met death in my life —who hasn’t?—but not on a mass scale. Hage’s story takes place amid the sectarian civil war that shredded Lebanon from 1975 to 1991. The war can be benchmarked not so much by its procession of political, religious, and military rivalries, but by massacres, shootings, bombings, with faction after faction and country after country, including the United States, sucked in and spat out. Time Magazine reported the damage in numerical terms: “The casualty toll, largely civilian: 144,240 people slain, 197,506 wounded and 17,415 missing. Most of the missing persons were abducted by rival militias, and are now presumed dead.” More than 200,000 Lebanese expatriates were scattered worldwide, including Hage himself who left Lebanon in the early 1980s, living first in New York City, then moving to Montreal in 1992.

A book set during a war that ended over 25 years ago could be called an historical novel. But Beirut Hellfire Society expresses an immediacy that pushes it out of the genre; it feels like it’s happening now, and in a way it is, as violence shatters cultures and pushes people around the globe. Hage told The Globe and Mail (Toronto), “Ultimately, this book is a reflection on a society that is in perpetual struggle between theocracy and some kind of secular government, and where theocracy is winning.” I respectfully contest his summation. The political and religious struggle over the agency of people’s bodies is certainly an essential aspect of the book, but for me it’s not the central concern of Beirut Hellfire Society. At risk of utter corniness, I’ll go ahead and say: Beirut Hellfire Society is a book about life and death, and humanity, including dogs, whom Pavlov considers more ideally human than humans.

Pavlov’s sympathies lie especially with the dead orphaned culturally or religiously, “the trapped, lost, ignored, dejected.” Despite the meanness that Hage’s living characters suffer at the hands of each other, and although the tone of the prose bends toward the sardonic, his story never descends to mean-spiritedness, for Pavlov’s generosity to the dead touches the living. If somebody’s body needs rescuing, even prehumously, he rescues it. He arranges that an extravagant debauchee gets the bizarre sendoff of his dreams. He drags a dead militiaman who once persecuted him across a killing zone, to be claimed by his comrades and lover. The father who bitterly regrets rejecting his now dead son comes to Pavlov for comfort. A woman begs him to disinter her, after death, from her detested husband’s side, where her children will plant her. Whether Pavlov liked or disliked the once-living people whose cadavers require his services, he will care for them, rescuing their bodies from what a fellow undertaker calls “the filth of earth” and according them the spontaneous mode of ritual passed to him by his father:

Pavlov’s sympathies lie especially with the dead orphaned culturally or religiously, “the trapped, lost, ignored, dejected.” Despite the meanness that Hage’s living characters suffer at the hands of each other, and although the tone of the prose bends toward the sardonic, his story never descends to mean-spiritedness, for Pavlov’s generosity to the dead touches the living. If somebody’s body needs rescuing, even prehumously, he rescues it. He arranges that an extravagant debauchee gets the bizarre sendoff of his dreams. He drags a dead militiaman who once persecuted him across a killing zone, to be claimed by his comrades and lover. The father who bitterly regrets rejecting his now dead son comes to Pavlov for comfort. A woman begs him to disinter her, after death, from her detested husband’s side, where her children will plant her. Whether Pavlov liked or disliked the once-living people whose cadavers require his services, he will care for them, rescuing their bodies from what a fellow undertaker calls “the filth of earth” and according them the spontaneous mode of ritual passed to him by his father:

‘The father turned to the cadaver, and with a singing, wailing voice he uttered these words: they say ashes to ashes, but we say fire begets fire. May your fire join the grand luminosity of the ultimate fire, may your anonymity add to the greatness of the hidden, the truthful and the unknown. You, the father continued, were trapped, lost, ignored, dejected, but now you are found, and we release you back into your original abode. Happy are those rejected by the burial lots of the ignorant. The earth is winter and summer, spring and fall… We heard your call and we came.”

Hage doesn’t presume to express belief in whether our efforts have any actual effect on the spirits of the dead, or even if the dead possess any attributes beyond a body. Death and war produce orphans and isolation. “I am alone,” one of Pavlov’s clients tells him. “Everyone around me has fled or died.” The mere sight of Pavlov’s vehicle, the “deathmobile,” creates its own zone of superstitious fear, hostility, and silence. The legacy Pavlov’s father passes to his son, who keeps it faithfully, is intended to mediate that lonely zone, when a body is caught between the life it had and whatever lies after death. “My father was an undertaker and now I am an undertaker.” Beirut Hellfire Society is not only about how the living and the dead face each other, it’s a book about a father and his child and what remains when the nature of the living bond between them is changed.

Hage doesn’t presume to express belief in whether our efforts have any actual effect on the spirits of the dead, or even if the dead possess any attributes beyond a body. Death and war produce orphans and isolation. “I am alone,” one of Pavlov’s clients tells him. “Everyone around me has fled or died.” The mere sight of Pavlov’s vehicle, the “deathmobile,” creates its own zone of superstitious fear, hostility, and silence. The legacy Pavlov’s father passes to his son, who keeps it faithfully, is intended to mediate that lonely zone, when a body is caught between the life it had and whatever lies after death. “My father was an undertaker and now I am an undertaker.” Beirut Hellfire Society is not only about how the living and the dead face each other, it’s a book about a father and his child and what remains when the nature of the living bond between them is changed.

Hage conveys tenderly the loneliness of the human body when stripped of its doings: its physical occupations, its fleshly contacts. The body is lonely when it’s just a body, but it takes loving eyes to see it that way. Is Beirut Hellfire Society a grim book? It depends on how you feel about death. Besides, a book with that title can’t entirely lack humor, even if its comic effects shimmer from behind a pall of grief and fear. Pavlov’s internal commentary, as he watches funerals from the balcony of his home, is both compassionate and satirical. Bachelors’ funerals are seen as last-ditch celebrations of the sacrament denied them by death; accordingly, the pallbearers dance:

“The six men lifting the box created the shape of a wobbly, mythical creature with twelve arms, twelve legs swaying its way towards the edge of a manmade pit. The band played tunes for which Pavlov made up various names: The Dance of Drunken Coffins, A Weeping of Happy Feet, An Enchanting Choice of Radio Music. And he would wonder about the positions of the grooms inside the boxes on their bumpy ride toward the grand altar below.”

Pavlov continues his reverie by musing on death customs of various ancient cultures, all part of “the dialectic that includes hermaphrodites and semi-gods, the Manichean stripes of zebras, double agents in war movies, Siamese twins, divided cities, border rivers and Homeric sirens of the sea,” a list that could describe not only the deities of his own chaotic and loosely held beliefs, but also the people he encounters on the job, a cast of eccentrics that draw Pavlov, and the reader, through the four seasons of the book, dancing with death all the way.

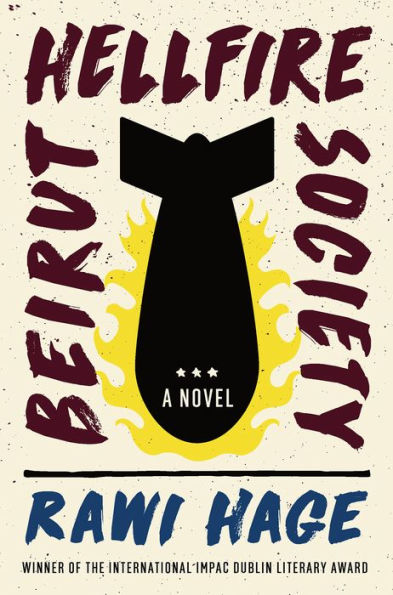

[Published July 16, 2019 by W.W. Norton, 288 pages, $26.95 hardcover]