“I write. It’s not my trade. No trade resembles man. It’s what I can do,” writes Georges Perros in the third and final edition of Papiers collés (Paper Collage), the aphoristic literary and philosophical jottings for which he is best known. He continues: “I know that if I’m not writing, something is not quite right and announces a catastrophe. I have friends who are crazier than I am. As a young man, I was also crazy. When I hadn’t turned out my daily ten pages of nonsense, I’d get sick. Or fall in love. Which amounts to the same thing. Now, it’s different. I’ve consorted with others. Writing no longer seems tragic to me. On the contrary. There’s worse. I believe writing is a privilege. A privilege for a poor man.”

Perros’ attitude embodies a habit shared by many writers: an alternating swing between grandiose ambition and crushing deflation. The hope of creating something that will endure encountering the sobering contemplation of demise. But Perros’ transit between the poles is so swift that the resulting statement is ultimately encouraging: the writer’s life is made whole – or at least given its mission — by way of its necessary extremes. But also, writing is a response to extremities: “A quill is the sharpest thing I’ve found … for breaking the poisoned sequence of time.”

Perros’ attitude embodies a habit shared by many writers: an alternating swing between grandiose ambition and crushing deflation. The hope of creating something that will endure encountering the sobering contemplation of demise. But Perros’ transit between the poles is so swift that the resulting statement is ultimately encouraging: the writer’s life is made whole – or at least given its mission — by way of its necessary extremes. But also, writing is a response to extremities: “A quill is the sharpest thing I’ve found … for breaking the poisoned sequence of time.”

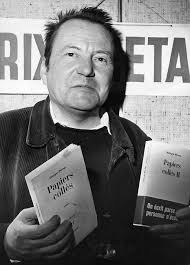

If you visit the town of Douarnenez in Brittany, you may discover that two famous personalities once lived there – René Laennec, the inventor of the stethoscope (1781-1826) — and Georges Perros (1923-1978) for whom the local médiatèque is named. Born in Paris as Georges Poulot, he renamed himself after a local Breton village, Perros-Guirec.

Having studied music and theater, Perros worked as an actor and play script editor in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, but he soon turned his energies to writing – poetry, reviews, and short essays. Gallimard published his only two collections of poems, the better known of which is Une vie ordinaire (An Ordinary Life), which he described as a “novel-poem” tracing his life story. On leaving Paris to live with his growing family in Douarnenez, Perros made his living from writing reviews, editing manuscripts, and doing a little teaching at the University of Brest. He cultivated a long correspondence with many Paris-based luminaries, some of which was published posthumously in France where Perros became a cult figure, especially among writers, after his death from cancer of the larynx.

The three volumes of Papiers collés (1960, 1973, 1978) are now available for Anglophone readers in John Taylor’s snappy translation. (In unedited form, Perros’ notebook entries run to over 1,000 printed pages.) Terseness is an obvious requirement for Taylor, but Perros demands more from a translator because even his briefest entries carry philosophical weight and suggestiveness. As Taylor says in his introduction, “The sight-reading initially seems not so difficult. But this is an illusion. Perros is working with the finest points of la langue parlée, not only at the semantic level but also at those of sound and social context.” Taylor has responded to the challenge with renditions of acute fluency and empathic understanding:

The three volumes of Papiers collés (1960, 1973, 1978) are now available for Anglophone readers in John Taylor’s snappy translation. (In unedited form, Perros’ notebook entries run to over 1,000 printed pages.) Terseness is an obvious requirement for Taylor, but Perros demands more from a translator because even his briefest entries carry philosophical weight and suggestiveness. As Taylor says in his introduction, “The sight-reading initially seems not so difficult. But this is an illusion. Perros is working with the finest points of la langue parlée, not only at the semantic level but also at those of sound and social context.” Taylor has responded to the challenge with renditions of acute fluency and empathic understanding:

“Although literature makes waste, at least it has a chance of making a man stand straighter. It’s important to understand this. Nearly all trades produce waste. Literature is one of the few occupations demanding rare willpower of a man, a way of running his existence that slows down the progress of a mediocrity that is natural to all of us.”

“Speech comes from a dream. But man is a dream. We contemplate one another as we’ll never be able to contemplate Nature which has no equal. We look at one another as if we were idiots and morons who were merely astonished, alarmed or threatened, and sometimes delighted. Words come from man’s permanent dream, which another man shows up to interrupt, and a dream rarely opts for an exchange, a conversation … whatever the other person’s response, however humiliating or wounding, we’ll never have to do anything else than go back to what we’ve actually never left – our dream.”

Paper Collage is noted for its maxims, but Perros also writes anecdotally and as a memoirist. To the French, “papiers collés” refers to “glued bits or scraps of paper” forming a collage. Perros modestly described himself as a “journalier des pensées,” a workman who labors with thoughts. In his poetry, Perros toiled in a liminal space “between the terror / and the pleasure of being alive.” He took on looming topics – the psyche and the self, solitude, love, friendship, family, culture, spirituality, and death. These also appear in Paper Collage. But in his fragments, which Perros seemed to find most suitable to his sense of incompleteness striving for its truest expression, he penetrated deeper. As he observes, “It would be good if a journal could be written in the same way that Picasso paints. A distorting journal that would show artistry.”

Paper Collage is noted for its maxims, but Perros also writes anecdotally and as a memoirist. To the French, “papiers collés” refers to “glued bits or scraps of paper” forming a collage. Perros modestly described himself as a “journalier des pensées,” a workman who labors with thoughts. In his poetry, Perros toiled in a liminal space “between the terror / and the pleasure of being alive.” He took on looming topics – the psyche and the self, solitude, love, friendship, family, culture, spirituality, and death. These also appear in Paper Collage. But in his fragments, which Perros seemed to find most suitable to his sense of incompleteness striving for its truest expression, he penetrated deeper. As he observes, “It would be good if a journal could be written in the same way that Picasso paints. A distorting journal that would show artistry.”

“That you have to love yourself a lot, indeed adore yourself, in order to put up with yourself a little, dooms all our relationships.”

“For years now I’ve no longer touched the woman who’s brave enough to live with me. This doesn’t prevent me from loving her. It prevents me from touching another woman.”

“Writing well is a meaningless notion. Today, you can hope only for a total rupture. This isn’t easy. You mustn’t do it intentionally, but rather live. What I like in a writer is what escapes him after he has done his eliminating. Literature makes sense only when it’s monstrous.”

There were moments while reading Paper Collage, which is so reliant on wit, when I wished for some monstrousness, some rupture of language. Perhaps the distortion he called for was beyond Perros’ range as a writer. Exactitude was his métier. It is as if he placed himself out of range in Douarnenez to contemplate his own limits of range and output. Nevertheless, the passionate mixture of assertion and negation in the prose pieces resonates for others far beyond whatever strictures he experienced.

Two years before his death, Perros underwent an operation that disabled his vocal cords. But he kept speaking through his journals. In 1978, his notebook Magic Slate was published posthumously to acclaim, beginning the rediscovery of Paper Collage in its entirety. Taylor includes Magic Slate in his volume. As an illness narrative, it anticipates the current taste for such memoirs:

“I must have treated myself as I did my motorcycles. Till they couldn’t take any more, and not bothering much about maintenance. Why does this hole in my neck make me think of the one in which a sparkplug fits? And the way I would bleed, of leaking oil?”

“I must have treated myself as I did my motorcycles. Till they couldn’t take any more, and not bothering much about maintenance. Why does this hole in my neck make me think of the one in which a sparkplug fits? And the way I would bleed, of leaking oil?”

“I no longer speak. So nobody speaks to me any more. They speak about me in front of me. And when someone is alone with me, he can’t wait to head out of the door. This is perfectly understandable. I can’t make anyone feel interesting any more – a hard job that I know how to do well. He pulls his ears down over his eyes. ‘How said it is’ …”

“A little respite at the thought of Rimbaud croaking not very far from here. And of Artaud, born nearby … Well then, I might as well croak here too!”

[Published by Seagull Books on May 18, 2015. 200 pages, $25.00 hardcover]

On Ruptures and Monstrosities

Thank you for yet another excellent review. It makes me want to read more. Perros sounds like a right case, alright — with an acute sense of the limitations of both language and feelings. Maybe I’m drawing a long bow here, but your third photo above suggests a man in a cave imposed upon by an interiority of words that have failed to work for him, encircled by an underground library where the exteriority of books has separated itself and the books themselves are no longer speaking. What happened there, you wonder? Then there’s Perros taking that a step further…until he’s running with that. And interesting, his Picasso analogy. Picasso the master, who generally makes me think of food, in the variety of his ways, of the flavours, the meal, and the chronic forgetfulness of satiety.