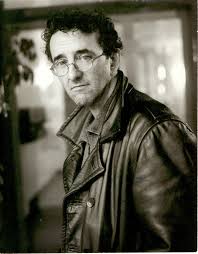

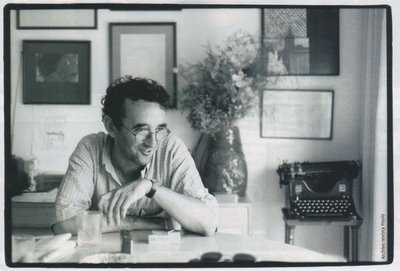

Borges, Cortázar, Bolaño. With the recent publication of Bolaño’s novels in English, the Anglophone critics now generally concur with their Hispanic colleagues: Bolaño, who died in 2003 in Catalonia, is the greatest novelist of his foreshortened generation, supplementing the imaginative portfolio of Borges (versus the magical realism of García Márquez). The fourth of his nine novels and novellas but the first to be published, The Savage Detectives appeared in 1998. He wrote almost all of his prose fiction, including many short stories, in the final decade of his life.

Born in 1953 in Chile, Bolaño mainly wrote poetry for twenty-five years while living in Mexico and Spain. Launching a poetry movement in the early 1970s called Infrarealism, Bolaño at the age of twenty-three wrote an excoriating manifesto with a Jacobin prediction: “The bourgeois and the petit-bourgeois live from party to party. They have one every weekend. The proletariat doesn’t have parties. Only regular funerals. That’s going to change. The exploited are going to have a big party. Memory and guillotines.” Natasha Wimmer, who translated The Savage Detectives, maintains that “in the last years of his life, when he published his novel The Savage Detectives, he achieved the radical break that his manifesto promised.”

Born in 1953 in Chile, Bolaño mainly wrote poetry for twenty-five years while living in Mexico and Spain. Launching a poetry movement in the early 1970s called Infrarealism, Bolaño at the age of twenty-three wrote an excoriating manifesto with a Jacobin prediction: “The bourgeois and the petit-bourgeois live from party to party. They have one every weekend. The proletariat doesn’t have parties. Only regular funerals. That’s going to change. The exploited are going to have a big party. Memory and guillotines.” Natasha Wimmer, who translated The Savage Detectives, maintains that “in the last years of his life, when he published his novel The Savage Detectives, he achieved the radical break that his manifesto promised.”

There was a radical break – but it was not from the mainstream of art and politics about which he had been furious for so many years. Bolaño broke from all facile, grooved conclusions – especially those of the revolutionary, a figure he had cultivated for himself during the fatal churn of power politics in Mexico City in 1968 and the early 1970s. He broke from past behavior and became his own singular aesthete, supposedly freed from his heroin habit, aching in his gut from liver disease, and now crafting artful novelistic objects that toyed with his readers.

An aggrieved person will always find a suitable object for grievance. Follow his writing through the years and one discovers how Bolaño gathered his talents to give shape and voice to his disappointments. In Bolaño’s novels, all political animals eat from the same trough – the raging poet and the calculating regime master. The artist or writer captivated by ideology is just as corrupt as the full-time fascist (who may also be a poet). Bolaño was a voracious reader all his life, but he remarked in an essay that the one novel that most influenced him was Camus’ The Fall in which a lawyer, mourning his dissipated potential, abandons his practice for a life of premeditated hypocrisy.

An aggrieved person will always find a suitable object for grievance. Follow his writing through the years and one discovers how Bolaño gathered his talents to give shape and voice to his disappointments. In Bolaño’s novels, all political animals eat from the same trough – the raging poet and the calculating regime master. The artist or writer captivated by ideology is just as corrupt as the full-time fascist (who may also be a poet). Bolaño was a voracious reader all his life, but he remarked in an essay that the one novel that most influenced him was Camus’ The Fall in which a lawyer, mourning his dissipated potential, abandons his practice for a life of premeditated hypocrisy.

It took Bolaño all his life to grow into that character in order to leverage its/his voice into the fully committed practice of writing. William Meredith wrote, “All the writers who go on concerning us after their deaths are men and women who have escaped from a confused human identity into the identity they willed and consented to.” This is why Bolaño’s fiction doesn’t represent a “radical break” from the supposed mainstream of art and politics he raged against in his manifesto. Rather, it embodies the maturation and strength of his will, the force of his consent, to produce unique fictions that live up to the psyche implied in his poetry.

This brings us to his verse, a taste of which is now available in The Romantic Dogs, translated ably by Laura Healy.

SELF PORTRAIT AT TWENTY YEARS

I set off, I took up the march and never knew

where it might take me. I went full of fear,

my stomach dropped, my head was buzzing:

I think it was the icy wind of the dead.

I don’t know. I set off, I thought it was a shame

to leave so soon, but at the same time

I heard that mysterious and convincing call.

You either listen or you don’t, and I listened

and almost burst out crying: a terrible sound,

born on the air and in the sea.

A sword and shield. And then,

despite the fear, I set off, I put my cheek

against death’s cheek.

And it was impossible to close my eyes and miss seeing

that strange spectacle, slow and strange,

though fixed in such a swift reality:

thousands of guys like me, baby-faced

or bearded, but Latin American, all of us,

brushing cheeks with death.

Healy’s collection offers no context for the composition of the poems — no commentary, no notes, just the bilingual versions. A poem of retrospection (written when?), “Self Portrait at Twenty Years” lays out the matured Bolaño position: a “mysterious and convincing call” remains alive, but it exists in a world of exhausted possibilities and looming mortality. The manifesto-writer once expressed his confidence in the currency of the language of his argument, in language itself. But Bolaño as middle-aged poet and novelist fully surrendered to the force of his own fictions. Once he stopped patronizing himself, the writing could be truly, shamefully vivacious, as scurrilous as the world his novels portrayed. The last years of his life, culminating with the graphomaniacal production of 2666, seem to reflect E.M. Cioran’s world-vision in which “we last only as long as our fictions.”

Healy’s collection offers no context for the composition of the poems — no commentary, no notes, just the bilingual versions. A poem of retrospection (written when?), “Self Portrait at Twenty Years” lays out the matured Bolaño position: a “mysterious and convincing call” remains alive, but it exists in a world of exhausted possibilities and looming mortality. The manifesto-writer once expressed his confidence in the currency of the language of his argument, in language itself. But Bolaño as middle-aged poet and novelist fully surrendered to the force of his own fictions. Once he stopped patronizing himself, the writing could be truly, shamefully vivacious, as scurrilous as the world his novels portrayed. The last years of his life, culminating with the graphomaniacal production of 2666, seem to reflect E.M. Cioran’s world-vision in which “we last only as long as our fictions.”

DIRTY, POORLY DRESSED

On the dogs’ path, my soul came upon

my heart. Shattered, but alive,

dirty, poorly dressed, and filled with love.

On the dogs’ path, there where no one wants to go.

A path that only poets travel

when they have nothing left to do.

But I still had so many things to do!

And nevertheless, there I was: sentencing myself to death

by red ants and also

by black ants, traveling through the empty villages:

fear that grew

until it touched the stars.

A Chilean educated in Mexico can withstand everything,

I thought, but it wasn’t true.

At night, my heart cried. The river of being, chanted

some feverish lips I later discovered to be my own,

the river of being, the river of being, the ecstasy

that folds itself into the bank of these abandoned villages.

Mathematicians and theologians, diviners

and bandits emerged

like aquatic realities in the midst of a metallic reality.

Only fever and poetry provoke visions.

Only love and memory.

Not these paths or these plains.

Not these labyrinths.

Until at last my soul came upon my heart.

It was sick, it’s true, but it was alive.

“The dogs’ path” is the same road on which “I set off” in “Self Portrait at Twenty Years.” Setting off on a dubious path is the central metaphorical act for Bolano – but it was transformed from juvenilia to serious literature only once he had willed a new identity for himself, no longer flattering the inflations of the rebel, but becoming the ultimate self-revolutionary, condemning himself to the guillotine. The labyrinths of human commerce, “a metallic reality,” fail to provoke him now. Although “only fever and poetry provoke visions,” this poem is hardly visionary. It depends on a simple trope — the soul is a dog, the heart is a bedraggled wanderer. The rest is comprised of abstractions. “Dirty, Poorly Dressed,” like most of Bolaño’s poetry, owes its mannerisms to the Chilean poet Nicanor Parra (b. 1914) who also constructs quasi-metaphorical scenes, as in these opening lines from “The Tablets,” translated by W.S. Merwin:

“The dogs’ path” is the same road on which “I set off” in “Self Portrait at Twenty Years.” Setting off on a dubious path is the central metaphorical act for Bolano – but it was transformed from juvenilia to serious literature only once he had willed a new identity for himself, no longer flattering the inflations of the rebel, but becoming the ultimate self-revolutionary, condemning himself to the guillotine. The labyrinths of human commerce, “a metallic reality,” fail to provoke him now. Although “only fever and poetry provoke visions,” this poem is hardly visionary. It depends on a simple trope — the soul is a dog, the heart is a bedraggled wanderer. The rest is comprised of abstractions. “Dirty, Poorly Dressed,” like most of Bolaño’s poetry, owes its mannerisms to the Chilean poet Nicanor Parra (b. 1914) who also constructs quasi-metaphorical scenes, as in these opening lines from “The Tablets,” translated by W.S. Merwin:

I dreamed I was in a desert and because I was sick of myself

I started beating a woman.

It was devilish cold, I had to do something,

Make a fire, take some exercise,

But I had a headache, I was tired,

All I wanted to do was sleep, die.

My suit was soggy with blood

And a few hairs were stuck among my fingers

They belonged to my poor mother –

“Why do you abuse your mother,” a stone asked me,

A dusty stone, “Why do you abuse her?”

Bolaño is now being shoved onstage in the costume of a pioneering “post-nationalist” writer. He once said, “I don’t believe in exile, especially not when the word exile is set beside the word literature,” and that his country of origin was poetry itself. But his transits through the Hispanic world seem to comport with John Berger’s view of emigration as “the quintessential experience of our time … Emigration does not only involve leaving behind, crossing water, living amongst strangers, but also undoing the very meaning of the world and, at its most extreme, abandoning oneself to the unreal which is the absurd.” The sound of poetry, as heard in Parra’s work, was the pacing of the untethered mind among the absurdities. But if Parra mocked the transcendent, Bolaño – with all the hearts and souls crying in his poetry – permits a whiff of a transcendental aura, or at least some movement to further understanding of what it means to search. The final lines of Bolaño’s poem “Parra’s Footsteps” read:

Bolaño is now being shoved onstage in the costume of a pioneering “post-nationalist” writer. He once said, “I don’t believe in exile, especially not when the word exile is set beside the word literature,” and that his country of origin was poetry itself. But his transits through the Hispanic world seem to comport with John Berger’s view of emigration as “the quintessential experience of our time … Emigration does not only involve leaving behind, crossing water, living amongst strangers, but also undoing the very meaning of the world and, at its most extreme, abandoning oneself to the unreal which is the absurd.” The sound of poetry, as heard in Parra’s work, was the pacing of the untethered mind among the absurdities. But if Parra mocked the transcendent, Bolaño – with all the hearts and souls crying in his poetry – permits a whiff of a transcendental aura, or at least some movement to further understanding of what it means to search. The final lines of Bolaño’s poem “Parra’s Footsteps” read:

The revolution is called Atlantis

And it’s ferocious and infinite

But it’s totally pointless

Get walking, then, Latin Americans

Get walking get walking

Start searching for the missing footsteps

Of the lost poets

In the motionless mud

Let’s lose ourselves in nothingness

There where the only things heard are

Parra’s footsteps

And the dreams of generation

Sacrificed beneath the wheel

Unchronicled

Carmen Boullosa was 20 years old in 1974 when she encountered Bolaño and his retinue at Mexico City poetry readings. In “Bolaño in Mexico” she writes, “With my own eyes I saw a group of Infrarealists (mission: sabotage) throw the contents of a glass over [Octavio] Paz (very smartly dressed, in an elegant blazer) who shook out his tie and continued conversation with a smile, as if nothing happened.” Indeed, nothing had. At another event, Bolaño “set out the reasons for his hatred of Paz: ‘his odious crimes in the service of international fascism, the appalling little piles of words that he risibly calls his poems, his abject insults to Latin American intelligence, that dreary excuse for a literary magazine which reeks of vomit and goes by the name of Plural.” Paz not only had Bolaño’s number, but made for a most inappropriate antagonist. They were too much alike in their literary enthusiasms and perceptions of Latin America. Paz was simply an adult. He later wrote in Itinerary, “The rebel is nearly always a solitary; his archetype is Lucifer whose sin was to prefer himself.” Young Bolaño exactly.

Carmen Boullosa was 20 years old in 1974 when she encountered Bolaño and his retinue at Mexico City poetry readings. In “Bolaño in Mexico” she writes, “With my own eyes I saw a group of Infrarealists (mission: sabotage) throw the contents of a glass over [Octavio] Paz (very smartly dressed, in an elegant blazer) who shook out his tie and continued conversation with a smile, as if nothing happened.” Indeed, nothing had. At another event, Bolaño “set out the reasons for his hatred of Paz: ‘his odious crimes in the service of international fascism, the appalling little piles of words that he risibly calls his poems, his abject insults to Latin American intelligence, that dreary excuse for a literary magazine which reeks of vomit and goes by the name of Plural.” Paz not only had Bolaño’s number, but made for a most inappropriate antagonist. They were too much alike in their literary enthusiasms and perceptions of Latin America. Paz was simply an adult. He later wrote in Itinerary, “The rebel is nearly always a solitary; his archetype is Lucifer whose sin was to prefer himself.” Young Bolaño exactly.

Not coincidentally, it is Octavio Paz who may provide the best way into Bolaño’s poetry. Paz wrote, “Every poem is an attempt to reconcile history and poetry for the benefit of poetry … Poetry is the other voice. Not the voice of history or of anti-history, but the voice which, in history, is always saying something different.” Bolaño’s preoccupation was to give voice to “our models of fear,” the final phrase in his poem “The Frozen Detectives.” The fear extended far beyond the political. One can hear the familiar apprehension in the final lines of his narrative “The Last Savage”:

I’d gone to see “The Last Savage,” and on leaving the theatre

had no place to go. In a sense I was

the character from the film, and my black motorcycle carried me

straight to destruction. No more moonlight dancing

on shop windows, no more garbage trucks, no more

of the disappeareds. I’d seen death mate with sleep

and I was spent.

[Published by New Directions on November 28, 2008, 160 pp., $15.95 paperback]

Bolaño translations

Here is an english translation of Bolaño’s Infrarealist Manifesto:

http://launiversidaddesconocida.wordpress.com/

Bolano in retrospective

This is a discerning point of view and one I haven’t encountered. This notion of Bolano’s shift into what you call “maturation” is truly illuminating not only in terms of explaining Bolano’s development but also in terms of explaining his basic relationship to poetry. Your points about Paz and history and Bolano are now in my own notebook. They explain a lot to me. Thank you for this essay.