Weapons Grade, poems by Terese Svoboda (University of Arkansas Press)

Again and again, one hears poets praised for “bridging the personal and the political,” but erecting these generally modest spans has become rather habitual for most American poets who include civic materials in their bag. In her sixth book, Terese Svoboda takes aim at an entire world. What results isn’t the usual associational transit between public and private realms.

Instead, the speaker of these ignited poems integrates serial war and marriage, child-rearing and genocide, through her petulance, disgust, cranky humor, and outraged conscience. It’s all one big human world violating itself.

Instead, the speaker of these ignited poems integrates serial war and marriage, child-rearing and genocide, through her petulance, disgust, cranky humor, and outraged conscience. It’s all one big human world violating itself.

Svoboda’s language lashes out. Its edges suggest danger, not with a honed sharpness but a jaggedness caused by the way she wrests words from conventional use. Her techniques are as plastic, playfully strange and unexpected as Heather McHugh’s, the means of a poet who is first of all a custodian of the language. Such conscientiousness about renewal of phrasing cultivates our respect – but Svoboda prefers that we esteem her offended tone and blunt situational assessments. The poems have no runways. They begin as if the speaker has been stewing and we arrive at very the moment she can’t restraint herself any longer.

AN OLD WAR

We mass, so many of us old,

with the old confusions of sex

and swarm, thrust and sting.

But we’re not wasps and bees.

Try meteors. Mom! you screech,

ducking head-under-arms.

Impotence is not in any animal’s genes,

it has to be earned. Forget the rockets’

red glare you so dearly love

and tear down that bright banner blood.

We can’t be moths attracted by light,

we must — boy — chew at the fuse.

Annoying bees at the fireworks. But the speaker wields her own sting, the pinch of her lesson. Her severity makes me flinch just as the boy must slightly recoil even as he loves the messenger and needs her protection. Her worry is about the “impotence” that may be his fate.

Annoying bees at the fireworks. But the speaker wields her own sting, the pinch of her lesson. Her severity makes me flinch just as the boy must slightly recoil even as he loves the messenger and needs her protection. Her worry is about the “impotence” that may be his fate.

The collection moves from the global to the domestic – but the urgent tone is constant, the phrasing unrelenting in its acuity and pressure.

BICOASTAL

Him in the sun is not fun.

every day of mine is a white bit

of kleenex, with not enough air

to float. Our son asks:

Is he back or forth? I say:

Dream him here.

A fog descends after his takeoff.

How much is memory? Twenty cents

he’s left on the bureau.

A month of cold phones, only food

children eat. My held breath is all

I’m counting up to.

Let the continent flex its bicep,

a man built on steroids. Absence

spreads – there’s nothing like presence.

Men invade, wreck and destroy, and depart. The women aren’t much better (“Livid, the blue infant she forgets in the sink, / slid so far on his side she thinks / he’s about to prove she’s truly jinxed”). There’s something knotted even in her most direct phrases, strangely complementing her prowess with forms. There’s the sound of conclusion but not the sense. Svoboda simply won’t relieve the tensions she creates – making Weapons Grade the great undetonated book of poems of 2009. Handle with extreme caution.

[Published September 4, 2009. 108 pages, $16.00 paperback]

* * * * * * * * *

Coal Mountain Elementary, poems by Mark Nowak, photographs by Ian The and Mark Nowak (Coffee House Press)

The catastrophe at the Upper Branch coal mine on April 5, the worst mining disaster in America since 1984, headlined the newscasts for a week. Soon it will fade from our concern. But Mark Nowak won’t let us forget. In works such as his play “Sago” and now Coal Mountain Elementary, he recovers the lost voices of labor, exposes the dominating language of the global coal industry, and lays bare the facts of human cost and environmental damage.

In Coal Mountain Elementary, Nowak returns his attention to the Sago Mine explosion of January 2, 2006. One reason why the deaths at Upper Branch seem so extraordinary is that earlier testimony about Sago, where twelve miners died and a rescue operation failed to save twelve others, was repressed by a junta comprised of the Department of Labor, federal and West Virginia mine safety officials, and the International Coal Group, the proprietor of the mine. Nowak revives and splices those testimonies, reports, and official statements as brief, untitled blocks of prose:

“I had a little rough time, especially – well, stumbling around because I have an artificial leg and it’s hard to walk on rough surface. The section foreman said I’m going back after my brother. So we told him he couldn’t do that. So I said, well, what about my brother-in-law, so I broke out in tears then. And he said, well, I’m going to try to go find them.”

“I had a little rough time, especially – well, stumbling around because I have an artificial leg and it’s hard to walk on rough surface. The section foreman said I’m going back after my brother. So we told him he couldn’t do that. So I said, well, what about my brother-in-law, so I broke out in tears then. And he said, well, I’m going to try to go find them.”

Nowak presents the corporate and governmental language as ragged, toneless poetry: “Procedure (cont.): 2. Explain that / the mining industry, / like any other business, / faces challenges / to make itself / profitable.” Excerpts from news reports lie on the page as italicized prose. The result is a startling, discomfiting procession of anguished speech and malevolent echoes.

Entwined with Sago is a second narrative line about mine disasters in China that details the cursory investigations there and summary firings of sacrificial officials. Here, the prose pieces are accompanied by Nowak’s and Ian Teh’s photographs of blasted and exhausted work environments. The human figure literally fades into the dust and smoke. Nowak’s bleak and moving images taken in West Virginia focus intently on a culture of community and its bruised spirit of endurance.

Nowak wrote on the Poetry Foundation’s “Harriet” blog on July 13, 2008, “The practice of reading and analyzing poetry as isolated or segregated from the policies and praxes of social movements and labor (i.e., the women, the men, and too often still today the children engaged in those jobs) doesn’t interest me much these days.” Yet Coal Mountain Elementary is not primarily a polemical book. It’s actually quite beautiful in its simultaneously subtle and blistering rhythms since the stories and pictures speak for themselves. Selecting, shooting, editing and arranging, Nowak has produced a riveting document of his own that we need to peer into events that shock but recede from our cultural memory before social justice may be enacted.

Nowak wrote on the Poetry Foundation’s “Harriet” blog on July 13, 2008, “The practice of reading and analyzing poetry as isolated or segregated from the policies and praxes of social movements and labor (i.e., the women, the men, and too often still today the children engaged in those jobs) doesn’t interest me much these days.” Yet Coal Mountain Elementary is not primarily a polemical book. It’s actually quite beautiful in its simultaneously subtle and blistering rhythms since the stories and pictures speak for themselves. Selecting, shooting, editing and arranging, Nowak has produced a riveting document of his own that we need to peer into events that shock but recede from our cultural memory before social justice may be enacted.

[Published April 1, 2009. 170 pages, 25 color photos, $20.00]

* * * * * * * * *

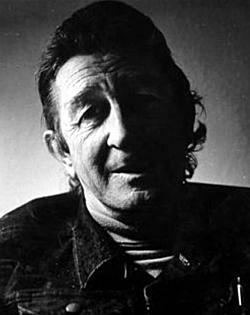

Eating the Pure Light: Homage to Thomas McGrath, edited by John Bradley (The Backwaters Press)

In The North Dakota Quarterly in 1983, Thomas McGrath (1916-1990) spelled out the dynamic features of “a poetry where the surrealist lions of Lorca and the classically magnetic lambs of Marvell and Crane fly up together: as a great beast of affirmation: absolute light. A poetry grand, armored, bawdy, seditious of death; of a violent elegance; as of clouds full of diamonds and lightning; of suicidal assaults on new states of being; of ultimate daring; of love, rage, generosity, failure, truth. And, at the other pole, the lone crow and darkness: Basho, Issa, the poetry of the moon. In between, the destructive element of a practical poesy — everything to help blow up the system: satire, japery, extravagance, humor, Brecht, case histories, parody, practical jokes, criticism. Everything against God, against Hollywood.”

The seventy-seven poets who contribute work to Eating the Pure Light embody these attributes in one way or another and combine to offer a truly affecting and stimulating homage to McGrath. The collection’s first section, “The Grip of McGrath,” features poems that recall McGrath and honor his mentorship. The second section, “Intrepid Wanderer,” contains shorter poems ranging across the subjects and places associated with McGrath. The poems of the third section, “Poems Against Fear,” speak directly to social and political issues. The final poems in “The Shoes of Tom McGrath” give ample evidence that our voices are carrying on with the engagement that McGrath inspired in three generations of poets.

The seventy-seven poets who contribute work to Eating the Pure Light embody these attributes in one way or another and combine to offer a truly affecting and stimulating homage to McGrath. The collection’s first section, “The Grip of McGrath,” features poems that recall McGrath and honor his mentorship. The second section, “Intrepid Wanderer,” contains shorter poems ranging across the subjects and places associated with McGrath. The poems of the third section, “Poems Against Fear,” speak directly to social and political issues. The final poems in “The Shoes of Tom McGrath” give ample evidence that our voices are carrying on with the engagement that McGrath inspired in three generations of poets.

McGrath knew a lot about the intractable intolerance of the American power structure. In his famous statement to HUAC the committee 1953, he said, “I regard this committee as usurpers of illegal powers and my enforced appearance here as in the nature of unreasonable search and seizure … [HUAC] is illegally engaged in the establishment of a religion of fear.” Since McGrath was a lifelong Communist, his words didn’t quite resonate with McCarthy, Nixon et al. But his poetic efforts to “help blow up the system” didn’t include attacking the personal nature of poetry itself and the viability of the first-person. He left that to others more intent on proclaiming themselves in the avant garde. The populist strain in the upper Midwest psyche was still quite strong in 1977 when Dave Clewell and I drove from Madison to Fargo to meet McGrath and read with him and other poets. McGrath simply cared more about the world than the word, as he frequently said.

FOR TOM MCGRATH / Dale Jacobson

It would be something if

the enormous elm crashed

in the storm but its shadow

with all its dark foliage

silhouetted by the street lamp

remained against the house.

And when the wind rises

the shadow rears up

a great spirit – its branches

reach toward the lattice

of lightning, and then:

the past, the shadow,

the house, tomorrow,

the stark fact of the world,

all revealed in a flash!

Jacobson’s poem is perhaps atypical of the main flow of Eating the Pure Light which tends towards the argumentative, outraged aspects of McGrath-land. But it represents an abiding, elemental, devotional mode of address among many midwest poets.

More than half of the poems here are culled from fairly recent publications, attesting to the enduring affect McGrath has on so many different writers: Philip Metres, Michael Henson, Ray Gonzales, Mark Nowak, Roseann Lloyd, Christopher Buckley, Joshua Weiner, Mark Vinz, Lee Sharkey, J.P. White, Estelle Novak, Doren Robbins, Warren Woessner, and many others. Basho, Marvell, Crane, Lorca – this line-up usually suggests discrete histories and styles, but McGrath, just like this lively collection, was a passionate integrator. The variety of his students’ work attests to the rightness of his embrace.

More than half of the poems here are culled from fairly recent publications, attesting to the enduring affect McGrath has on so many different writers: Philip Metres, Michael Henson, Ray Gonzales, Mark Nowak, Roseann Lloyd, Christopher Buckley, Joshua Weiner, Mark Vinz, Lee Sharkey, J.P. White, Estelle Novak, Doren Robbins, Warren Woessner, and many others. Basho, Marvell, Crane, Lorca – this line-up usually suggests discrete histories and styles, but McGrath, just like this lively collection, was a passionate integrator. The variety of his students’ work attests to the rightness of his embrace.

[Published February 9, 2009. 155 pages, $20.00 large-format paperback]

Nice to see your review of the McGrath anthology

Anthologies, esp. homages to deceased writers, never seem to get much attention, so I was glad to re-noticed this one. I also didn’t realize that you and Dave had met McGrath (where was I?). I did hear him read once at the Loft – very much like a character our of a Woody Guthrie song.

Best energy

Warren

Fargo Reading

Remember the Midwest Distribution Service HQ’d in Fargo? They distributed ABRAXAS and THE CHOWDER REVIEW. MDS hosted that reading in Fargo. Some others I recall being there — Allan Kornblum, Mark Vinz. Then we had an MDS planning meeting and everyone drank a lot of beer.

On Weapons Etc.

“It’s all one big human world violating itself.”

Ms Svoboda, Mr Nowak and the Coal Mountain Elementary crew — “undetonated” indeed — seem to be arguing very much against the suicide of the world.

Here in the Middle Kingdom, where I live, the middle-class people also like to congratulate themselves on their material successes, landing on the runway without much traction, toasting the great and unlikely satisfaction of their luck; the frequent mine accidents are forgotten as fast as possible, not poeticized — as the “development” trope is regularly deployed to distract them from caring very much.

Handle with care, yes…the record of blame, the world and the word, all the care it takes to live in it.

As always, many thanks for writing these reviews with such feeling.