Sally Ball’s second book of poems begins with modesty as its mien. Addressing a nuthatch, the speaker poses “no threat” because she loves “to make no difference here.” She goes on: “My throat like yours — / rapid little tremor, / heart-freight, air.” As slight presences show up here and there, Ball’s tone signals a desire to accommodate and be one of them. In “’Tis Often Thus with Spirits,” life is composed of “fretful particles.”

But as it turns out, she intends and makes a very great difference in these poems. Her book’s title, Wreck Me, is both a command and a daring taunt. In the first instance, speaking as a small thing in the crosshairs, she is saying hurt me, it’s my fate. In the latter instance, she heckles go ahead, just try. Her nature grates against her fate. The duality provides the poems’ subtle but deep undercurrent of tension.

But as it turns out, she intends and makes a very great difference in these poems. Her book’s title, Wreck Me, is both a command and a daring taunt. In the first instance, speaking as a small thing in the crosshairs, she is saying hurt me, it’s my fate. In the latter instance, she heckles go ahead, just try. Her nature grates against her fate. The duality provides the poems’ subtle but deep undercurrent of tension.

Or I should say “dualities,” because there are several of them: solitude versus companionability and family, violence intimidating survival, survival of spirit requiring a violence of mind. In the multi-part title poem, she asks, “Is it time to relinquish / everything, ours a life to study / not inhabit anymore?” One finds here a dissecting intelligence yielding to passive observances – but in the transition, there’s an exposed, irritated nerve-ending. Finally, in her phrasing and lines, there’s a rocking between the habitual and the unverified, willed performance and shaky audition.

MONSOON

I wanted the storm to hit, surely more

than I wanted the previous weather,

a dense, numbing kind of pressure.

I must have wanted the strike of it.

Clean sky after:

so utterly open one gets dizzy looking out,

falling away from the world,

away and away into that blank.

We wanted the storm? or required it — ?

But needing to be harrowed

and being harrowed —

even when you provoke it somehow,

or vault there,

it’s not as you’ve imagined, not what I

imagined. I can’t deliver it: the name

of the storm I always register

as a French pronoun, mine

mon

my swoon?

my imminent what?

And even having craved the storm,

(coward need)

even having opened to its electric violence

(no hiding in the archway,

duct tape across the windows)

I must have had in mind ensuing calm.

And now the sky completely different, indifferent.

But clear.

A morning, our morning,

stars held back behind the light.

The querying of this fascination with the storm’s turbulence, “the strike of it,” is itself another storm – the poem’s unsteady shift between uncertainty and assertion, utterances both fragmented and complete, make it so. There is an unsettling of accounts between shame and courage, swoon and a stiffened spine. Also, the portrayal of feeble attempt (”I can’t deliver it”) spars with the achieved win of the poem itself. Ball simply won’t give in to the blandishments of the settled world, even as she integrates that world into a more turbulent whole.

The world of Wreck Me is dominated by separating forces, a desert world full of space. Its dilations and ebbings are equally stunning. In “Sky Islands,” the sky says,

Sometimes I am Orion, armed

and tall and potent. Sometimes I’m a speck

of utter nothing. The dark at first domain,

then later depthless, obliterating.

This is also a slant micro-self-portrait of Ball’s speaker, sometimes talking quaintly with humility, sometimes taking on whatever is thrown at her and measuring up. What deeply impresses me about Ball’s work is her resistance to the allure of tone alone, of cutting a certain figure for the reader to consider gorgeous and mysterious. Instead, she presents the density of a mind struggling and thinking. You can sense it in the unsettled leaps between ideas and the disquieting and sometimes jagged shape of the lines, alternating with a clarity of statement that may sound resolute or desperate.

This is also a slant micro-self-portrait of Ball’s speaker, sometimes talking quaintly with humility, sometimes taking on whatever is thrown at her and measuring up. What deeply impresses me about Ball’s work is her resistance to the allure of tone alone, of cutting a certain figure for the reader to consider gorgeous and mysterious. Instead, she presents the density of a mind struggling and thinking. You can sense it in the unsettled leaps between ideas and the disquieting and sometimes jagged shape of the lines, alternating with a clarity of statement that may sound resolute or desperate.

Some poems are extended acts of looking. The object has protean qualities – the object and the eye that tracks it down have an indeterminate, fluctuating relationship. In the end, the looker exposes her own eye and her intention to capture to the judgment of the reader – as if description, left uninterrogated, merely seeks to reflect credit on the looker.

I SAW HIM SILHOUETTED AT SUNDOWN,

IN THAT LIGHT HE WAS GRAY

The white horse is not exactly white,

though his overall effect is whiteness of horse,

white disruption in the silvery field.

His muzzle, charcoal,

his forelock about the color

of my own dirty-blonde hair.

Large veins lift against

the whiteness of his soft cheek.

His blood moves full of messages –

he is a system of synapses

and pulleys and generally so like us

with our ligaments, rippling, healing,

out slightest movements, all the electrons

in sync … He is a deep looker,

a soft white bulletin about attention.

Or inwardness. He sees through me, as you do.

He withstands the enormous pressure

of the wind and sky, of being seen.

Recall the “numbing kind of pressure” in “Monsoon,” the weather that is unlike the storm. To be seen is to be categorized, defined. She bristles against such narrowing habits – then seems to revert to thoughts of “ensuing calm.” In this way, Ball skirts sententiousness – she advises on better ways of perceiving, then allows us to “see through” her. These precocious complexities are managed with a deft, gentle touch.

Later in the collection, in “Tributary,” she writes, “About the sea we love the combination / comfort and menace, the sense of water / gently holding us, of depths engulfing …” Comfort and menace frame Wreck Me but Ball doesn’t permit the reader to be charmed by a convenient theme or decorative arrangement. Here again, she points to smallness that is not a diminution: “we love to be the smallest particle, / germinal, relieved of any prowess / or conviction about prowess, // about control.” When we see through her, we acknowledge her passion – and ours — for prowess.

Later in the collection, in “Tributary,” she writes, “About the sea we love the combination / comfort and menace, the sense of water / gently holding us, of depths engulfing …” Comfort and menace frame Wreck Me but Ball doesn’t permit the reader to be charmed by a convenient theme or decorative arrangement. Here again, she points to smallness that is not a diminution: “we love to be the smallest particle, / germinal, relieved of any prowess / or conviction about prowess, // about control.” When we see through her, we acknowledge her passion – and ours — for prowess.

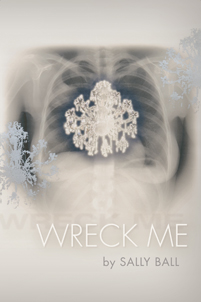

There is a consistently affectionate note in Ball’s work, shout-outs to the ones she loves. There are several poems about her father’s long wait for a lung transplant, the required wreckage of surgery. But there is also a “predatory urge” in moments when “hopelessness about our possible / return to forging on” becomes dominant. Personal strifes find analogs in the natural world. Her readers are witnesses to the unpredictable and complete vision of life that comprises Wreck Me. The final lines are addressed to us as much as to her closest presences:

Here we are. We’ve brought the center

to the edge.

I wake you with my hands.

[Published by Barrow Street Press on April 15, 2013. 56 pages, $16.95 original paperback]