Admired by the likes of Kafka, Musil, and Walter Benjamin, and acclaimed “unforgettable, heart-rending” by J. M. Coetzee, Swiss writer Robert Walser (1878-1956) remains one of the most influential authors of modern literature. Walser left school at fourteen and led a wandering, precarious existence while producing poems, stories, essays, and novels. In 1933, he abandoned writing and entered a sanatorium, where he remained for the rest of his life. “I am not here to write,” he said, “but to be mad.”

Admired by the likes of Kafka, Musil, and Walter Benjamin, and acclaimed “unforgettable, heart-rending” by J. M. Coetzee, Swiss writer Robert Walser (1878-1956) remains one of the most influential authors of modern literature. Walser left school at fourteen and led a wandering, precarious existence while producing poems, stories, essays, and novels. In 1933, he abandoned writing and entered a sanatorium, where he remained for the rest of his life. “I am not here to write,” he said, “but to be mad.”

The eight poems to follow here, included in the first publication of Walser’s collected poems translated for anglophones, allow readers to experience the author as he regarded himself at the beginning and end of his literary career — as a poet.

/ / / / /

Onwards

I wanted to stand still,

I urged myself further,

past black trees,

but beneath black trees,

I wanted to suddenly stand still,

I urged myself further,

past green meadows,

but next to those green meadows,

I only wanted to stand still,

I urged myself further,

past needy little cottages,

beside one of those cottages,

I really wanted to stand still,

regarding its need,

and how the smoke gently

rises into the sky, I would

like to stand still now awhile.

That’s what I said and laughed,

the green of the meadows laughed,

the smoke rose smiling like smoke,

I urged myself further.

* * * * *

Too Philosophical

How ghostly my life

in its fall and rise.

Always I see myself waving to myself,

floating away from the one waving.

I see myself as laughter,

as deep mourning again,

as a wild weaver of talk;

but all this falls away.

And all this time it has

never been quite right.

I have been chosen to

wander forgotten distances.

* * * * *

Doll

Please look at me for once,

do you not find me dignified?

I am a doll, I have very

interesting eyes that are

only made of glass and thus

are not good for much.

My limbs are full of sawdust.

Walking is simply impossible,

sitting works somewhat better,

and I am very good at lying down.

I have never done any work,

my hands are way too stiff,

my lips remain forever sealed,

they have never uttered a word,

my voice has never been heard.

Dolls are silent like fish.

I cannot laugh or cry.

Pain and joy, hate and love

I let people deal with,

who as we know get

emotional only too quickly.

I am always at the mercy

of some kind of change,

I am never frightened,

nothing unsettles me,

I feel, think, sense nothing

at all and I am apathetic

quite in the extreme.

To startle dolls out of their

sleep is hardly possible.

You see me constantly

making the same strange face.

I have never had a soul,

affection is utterly alien to me,

I am a sort of phenomenon

when it comes to immutability,

what a disgraceful confession!

Is a doll a doll

because of its liveliness?

I am based on, maintained

by illusion, simple as that.

Children appreciate me;

to them I am in every way

more than welcome as a plaything,

they can busy themselves with me,

because they have imagination.

Adults, on the other hand,

most certainly feel that

they are superior to me.

There is a reason for this,

of course, as I am generally

speaking unbelievably unhelpful.

To act on my own is something

that would never cross my mind,

I am utterly dependent

on the support of others.

There is plenty of evidence

that I am unusually

lifeless, stiff and dry.

To a child’s mind, however,

I am absolutely alive,

I eat, drink, go on walks,

lie down in bed just like a real person

and charm them with my talk;

and all this is only imagined,

and can easily add this

and that imaginary thing.

O, the little ones are so much

smarter than the big ones think.

It is they who know how to live.

* * * * *

The Comfort of Complaining

No one should feel abandoned,

yet I think there are many who

imagine themselves to be alone.

Here I live like a child enchanted

by the idea that I have been forgotten.

Perhaps there are only a few of us who can

bounce back in this way. Everywhere, I say,

there is some sun and wind and shadows

and sparkling moments of happiness

and sorrow swooping down on the soul

like an eagle from the heights of humanity.

Of course, people forget each other

quickly, but I believe everyone

is to blame for the fact

that those who were forgotten

were forgetful themselves.

To complain about something so natural

has a certain comfort sometimes.

* * * * *

The Benefits of Talking

Whatever we can talk about to one another,

our watchful eyes have seen it already.

Talking tries hard to be good for something,

and that talk replaces a world for us.

* * * * *

To a Writer

Gladly I would like to read the book

you wrote with your most earnest soul.

My so very funny stories are beginning

to bother me quite a bit, so to speak,

because I am afraid that they have made

many a reader dreary, dull and dead.

You, for example, never laughed it up;

you have always stepped in front of your

readership with the same solemn face,

they heard you pray with a devout voice,

and you gave courage and comfort to the world.

Because I was being funny with my quill,

some kind of remorse, if you know what I mean,

weighs on me, and that is why I would like

to delve into your work’s assiduousness;

I am light-heartedly writing poem after

poem, while you are serious, and that is why

you are probably the better and more dignified

man, and all of the funny things I have written

so far are making me sombre; you too are

one of those who cannot really stand me.

While reading your book, I feel like, now

that spring has returned with leaves and flowers,

comparing myself to your way of doing things.

* * * * *

Self-Reflection

Because they did not want me to be young, I became young.

Because I should have been a sufferer, many pleasures

flattered me.

Because they tried their best to put me in a bad mood,

I sought and found ways into such moods more welcome than

I could ever have wanted.

Since they impressed fear on me, courage cheered and laughed

with me.

They abandoned me, so I learned to forget myself,

which allowed me to bathe myself in blissfulness.

When I lost much, I realized that losses are winnings,

because no one can find something he did not first lose,

and to discover what is lost is worth more than any safe

possession.

Because they did not want to know me, I became self-aware,

became my own understanding and friendly doctor.

Because I found enemies in my life, I attracted friends,

and friends dropped away, but enemies too stopped being

hostile,

and the tree that bears the most beautiful fruits of luck is called

misfortune.

On life’s path, we lift all the peculiarities given to us

by our birth, our family home and our schools,

and only those who could not help but strain themselves need

to be rescued.

No one who is content with himself ever needed help,

unless he happened to be in an accident and needed to be

carried to the hospital.

* * * * *

I Wish I Had

I wish I had not yet written all those things,

there being nothing more to say on my part.

I wish someone here would help me be funny,

sometimes I feel ill-humoured on this earth.

If I had only drunk coffee instead of two glasses

of beer, there could still be hope for this poem,

which is being written now and so very smoothly,

even though it is unspeakably silent around me,

I could not wish for a more undisturbed silence,

even though I perhaps could allow myself something else.

I do not know whether I should have eaten sausage today

rather than cheese and whether I can still save this little poem,

which seems broken to me. As Herman Hesse

is known to do sometimes, I make a face like an idiot.

Admittedly, I wish I had not just said that,

it does not seem very elegant to me,

but now I will sleep long, until the next day.

/ / / / /

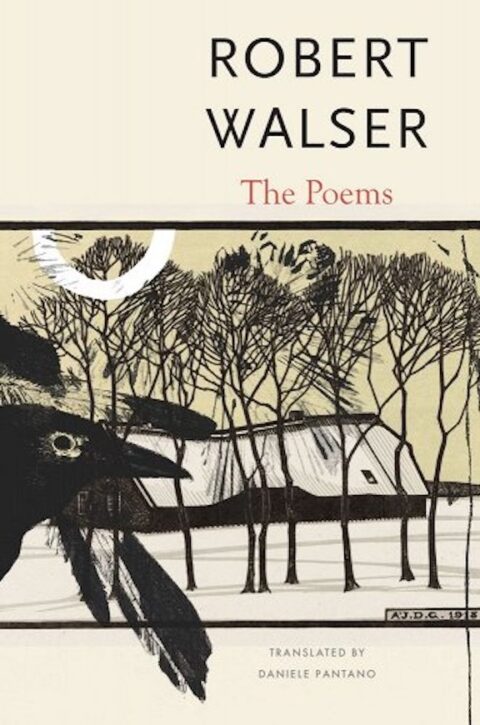

We are indebted to Seagull Books for their permission to excerpts these selections from Robert Walser: The Poems, translated by Daniele Pantano. You can acquire a copy of this splendid collection from Bookshop.org by clicking here.

We are indebted to Seagull Books for their permission to excerpts these selections from Robert Walser: The Poems, translated by Daniele Pantano. You can acquire a copy of this splendid collection from Bookshop.org by clicking here.

The poems:

“Onwards,” written 1899/1900, from Gedichte (1909)

“Too Philosophical,” from Gedichte (1909), first published in the Wiener Rundschau (1899)

“Doll,” written in Biel 1919-1920, first published in Die Rheinlande (1919)

“The Comfort of Complaining,” written in 1930, originally titled “The Comfort of Forgetting,” unpublished.

“The Benefits of Talking,” written in 1930, unpublished.

“To A Writer,” first published in Prager Presse, 1933.

“Self-Reflection,” written in 1925, first published in Prager Presse, 1933.

“I Wish I Had,” written in 1928, first published in Die literarische Welt, 1928