In September, 2009, an art collective called Bernadette Corporation exhibited “The Complete Poem” at Greene Naftali, a commercial gallery in Chelsea. The show comprised 38 quasi-fashion photographs by David Vasiljevic, and a 130-page epic poem by Eileen Myles called “A Billion and Change.” The pages were displayed under Plexiglas on thirteen long, slim, wooden tables and were offered individually for sale. Bernadette Corporation’s principal members at the time were Bernadette Van-Huy, Jim Fletcher, John Kelsey, and Antek Walczak.

In the second essay of Where Art Belongs, novelist, publisher and art critic Chris Kraus writes, “Audaciously, Bernadette Corporation insisted on treating the 130-plus pages of ‘A Billion and Change’ as original artwork. No press copies, no posting online, no Xeroxed handouts. As John Kelsey recalls, ‘Some of our most politically correct friends were outraged that we weren’t passing the poem out for free or putting it online’ … ‘One thing we knew,’ Antek Walczak recalls, ‘was we didn’t want to present the poem as a gallery reading, where everyone comes in and leaves. We didn’t want that effortless transmission.’”

In the second essay of Where Art Belongs, novelist, publisher and art critic Chris Kraus writes, “Audaciously, Bernadette Corporation insisted on treating the 130-plus pages of ‘A Billion and Change’ as original artwork. No press copies, no posting online, no Xeroxed handouts. As John Kelsey recalls, ‘Some of our most politically correct friends were outraged that we weren’t passing the poem out for free or putting it online’ … ‘One thing we knew,’ Antek Walczak recalls, ‘was we didn’t want to present the poem as a gallery reading, where everyone comes in and leaves. We didn’t want that effortless transmission.’”

Kraus notes that while displaying poetry like a work of visual art “was disturbing to most … it was especially terrifying to visual artists, whose miscomprehension of poetry rivals the philistine mantra of mid-century dentists – ‘My four-year-old could have done that!’ – when looking at paintings by Abstract Expressionists.”

The transparent clarity of Kraus’ writing allows us to comfortably tour the galleries at her elbow, perhaps hardly noticing that she gives us the language necessary to rid ourselves of “miscomprehensions” about where art belongs and what it consists of – as well as the illusions that we can easily slip through the grip of globalized capitalism into heroic expression. In the process, her essays give subtle encouragement to all artists to reconsider practices in light of the exciting, exceptional shows and events she attends and participates in. Her tastes are highly partisan, yet with stylish restraint she makes it easy for us to see the art, the artists, and their expressive moments in the context of the matrixed culture.

The transparent clarity of Kraus’ writing allows us to comfortably tour the galleries at her elbow, perhaps hardly noticing that she gives us the language necessary to rid ourselves of “miscomprehensions” about where art belongs and what it consists of – as well as the illusions that we can easily slip through the grip of globalized capitalism into heroic expression. In the process, her essays give subtle encouragement to all artists to reconsider practices in light of the exciting, exceptional shows and events she attends and participates in. Her tastes are highly partisan, yet with stylish restraint she makes it easy for us to see the art, the artists, and their expressive moments in the context of the matrixed culture.

Where Art Belongs opens with a piece on the two-year duration of Tiny Creatures, a gallery and musicians’ hangout opened in L.A. by Janet Kim in 2006. Kraus goes on to consider the strange journeys, “hyperappearances,” and paintings of Elke Krystufek in 2006, Moyra Davey’s “32 Photos From Paris,” and George Porcari’s photography culminating in his 2009 work Aventuras Con Tio César. Here is a sample of Kraus’ prose as she discusses Porcari:

“People and their behavior in the present chaos … Porcari’s work sets out to show something like this, but while people often appear in his pictures, they aren’t the subject. Deceptively ambient, the photographs are in fact highly composed and intentional. There are no portraits in Porcari’s work. Everyone in his world is a bystander … Porcari sees the third-world as a participant. His photographs neither depict deplorable squalor nor suggest any reason to celebrate the ‘common humanity’ shared by viewers and subjects. In fact, as his numerous series shot all over the world seem to show, there really isn’t much difference between the lunchtime crowd outside Time Warner in midtown Manhattan, the tourists gathered at Machu Picchu, or the skinny Latino men in New York sitting on cars beside a Union Square juice cart. … Porcari’s work suggests a world in which the person is no longer defined by any innate singularity, but by his or her place in a state of perpetual flux.”

“People and their behavior in the present chaos … Porcari’s work sets out to show something like this, but while people often appear in his pictures, they aren’t the subject. Deceptively ambient, the photographs are in fact highly composed and intentional. There are no portraits in Porcari’s work. Everyone in his world is a bystander … Porcari sees the third-world as a participant. His photographs neither depict deplorable squalor nor suggest any reason to celebrate the ‘common humanity’ shared by viewers and subjects. In fact, as his numerous series shot all over the world seem to show, there really isn’t much difference between the lunchtime crowd outside Time Warner in midtown Manhattan, the tourists gathered at Machu Picchu, or the skinny Latino men in New York sitting on cars beside a Union Square juice cart. … Porcari’s work suggests a world in which the person is no longer defined by any innate singularity, but by his or her place in a state of perpetual flux.”

Not only does Kraus’ narrative lead me to look up Porcari, but she gently yet firmly directs me to self-critique. Isn’t this the moment to mobilize “strands of ideas and experiences into provocative gestures that – like the best poems – avoid programmatic critiques and their implicit, misleading ‘solutions’”?

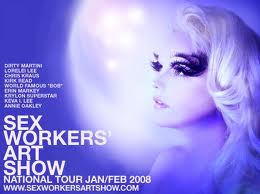

In the 1980s, Kraus worked for a time as a topless dancer. With this credential, she joined the cast of the Sex Workers’ Art Tour in 2008, the subject of her essay “Detour.” The tour founder, Tara Perkins, was pilloried by Laura Ingraham on Fox News. The troupe’s scheduled appearance at the College of William and Mary alarmed both ardent Republicans and Education Department professor John Foubert who warned, “the Sex Workers’ Art show is likely to bring increased sexual aggression … exposing people, particularly men, to pornography makes them more likely to commit sexual assault.” Kraus writes, “‘Are you for or against sex work?’ American youth wants to know, from Harvard to Duke to UC Davis. The question strikes all of us in the vans as absurd. It’s like asking if someone if “for” or “against” global capitalism.” Meanwhile, Perkins says, “I’m not doing the show to valorize sex work. We all know what that’s about. The show is a way to bring people together, and maybe open their eyes to other issues. I mean, would anyone come of I did an art show with fast-food workers?” In the show, Kraus reads a piece written for the tour on New York’s pre-AIDs hustle bars: “Where else except, perhaps, pre-glasnost Russia or Poland could a writer of literary fiction read to standing-room only crowds of 600 people?”

In the 1980s, Kraus worked for a time as a topless dancer. With this credential, she joined the cast of the Sex Workers’ Art Tour in 2008, the subject of her essay “Detour.” The tour founder, Tara Perkins, was pilloried by Laura Ingraham on Fox News. The troupe’s scheduled appearance at the College of William and Mary alarmed both ardent Republicans and Education Department professor John Foubert who warned, “the Sex Workers’ Art show is likely to bring increased sexual aggression … exposing people, particularly men, to pornography makes them more likely to commit sexual assault.” Kraus writes, “‘Are you for or against sex work?’ American youth wants to know, from Harvard to Duke to UC Davis. The question strikes all of us in the vans as absurd. It’s like asking if someone if “for” or “against” global capitalism.” Meanwhile, Perkins says, “I’m not doing the show to valorize sex work. We all know what that’s about. The show is a way to bring people together, and maybe open their eyes to other issues. I mean, would anyone come of I did an art show with fast-food workers?” In the show, Kraus reads a piece written for the tour on New York’s pre-AIDs hustle bars: “Where else except, perhaps, pre-glasnost Russia or Poland could a writer of literary fiction read to standing-room only crowds of 600 people?”

In “May ’69,” Kraus revisits the Paris demonstrations and riots, regarded here as the tipping point when “the word ‘liberation’ would migrate from a term to describe postcolonial struggles to include all aspects of daily life.” And perhaps this is the spirit Kraus injects throughout her writings – and which may have receded as a prime impulse of younger poets and artists who may be more inclined to ironically mimic or otherwise incorporate the culture that has co-opted them. In “May ’69,” Kraus tells the history of Suck – The First European Sex Paper, founded in 1969 by writers Germaine Greer and Heathcote Williams, the model Jean Shrimpton, and publishers Jim Haynes and Bill Levy. She writes, “While in our decade the ‘personal’ has become so debased by its confessional-therapeutic connotations that numerous artists choose to anonymize their production, Suck’s authors viewed disclosure not as personal narcissism but as a means of escaping the limits of ‘self.’”

In “May ’69,” Kraus revisits the Paris demonstrations and riots, regarded here as the tipping point when “the word ‘liberation’ would migrate from a term to describe postcolonial struggles to include all aspects of daily life.” And perhaps this is the spirit Kraus injects throughout her writings – and which may have receded as a prime impulse of younger poets and artists who may be more inclined to ironically mimic or otherwise incorporate the culture that has co-opted them. In “May ’69,” Kraus tells the history of Suck – The First European Sex Paper, founded in 1969 by writers Germaine Greer and Heathcote Williams, the model Jean Shrimpton, and publishers Jim Haynes and Bill Levy. She writes, “While in our decade the ‘personal’ has become so debased by its confessional-therapeutic connotations that numerous artists choose to anonymize their production, Suck’s authors viewed disclosure not as personal narcissism but as a means of escaping the limits of ‘self.’”

But my favorite of the eleven essays is “Indelible Video,” her associative, discursive essay on the ubiquity of video imagery. Looking back at the first video art collectives, she says, “The aesthetic was process, and for a short time many people truly believed this new technology would transform media culture into an open, interactive democracy.” That, too, was the rising vision of the Internet in the late 1990’s. Not cynicism but shifting enthusiasms mark Kraus’ perspective. “Like pornography, art no longer exists because it is virtually everywhere,” she writes. But the best conceptual art “attains its own life by cannibalizing the half-lives of its sources.” Where Rosalind Krauss once described the power of video art to “enact a collapsed and continuous present,” Chris Kraus now extends the notion: “Three decades later, this is the default-state of daily life across the matrix. Information abounds and the truest dynamic behind movement is commerce.”

But my favorite of the eleven essays is “Indelible Video,” her associative, discursive essay on the ubiquity of video imagery. Looking back at the first video art collectives, she says, “The aesthetic was process, and for a short time many people truly believed this new technology would transform media culture into an open, interactive democracy.” That, too, was the rising vision of the Internet in the late 1990’s. Not cynicism but shifting enthusiasms mark Kraus’ perspective. “Like pornography, art no longer exists because it is virtually everywhere,” she writes. But the best conceptual art “attains its own life by cannibalizing the half-lives of its sources.” Where Rosalind Krauss once described the power of video art to “enact a collapsed and continuous present,” Chris Kraus now extends the notion: “Three decades later, this is the default-state of daily life across the matrix. Information abounds and the truest dynamic behind movement is commerce.”

In their magazine, Bernadette Corporation wrote, “There is nowhere to go or hide or to remain untagged, unlogo’d, undiscovered, unstamped … names and tags will hover over every cosmic labyrinth.” Where Art Belongs is a timely, spirited, and often quotable update on a situation facing every artist of every genre. To read Chris Kraus is necessarily to respond to her, and to respond in this case is to think again.

[Published by semiotext[e] / intervention series) on March 15, 2011. 173 pages, $12.95 paperback. Distributed via MIT Press]