C.G. Jung has helped generations of adults to get even with those who misunderstood them as children – or at least, he has long been impressed into that service. An often-quoted line from his essay “Paracelsus” abets revenge: “Nothing has a stronger influence psychologically on their environment, and especially on their children, than the unlived life of the parents.” Neglecting their true desires and latent potential, the repressed, unenlightened parents allegedly screw up their kids for life.

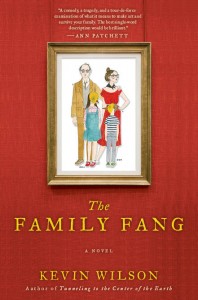

But what happens when the parents pursue their true desires to the limit? What are true desires anyway? And what about children who impede their parents’ efforts to attain artistic goals? Kevin Wilson’s comic first novel, The Family Fang, turns Jung’s proclamation (and our aggrieved and rutted use of it) on its head. His spirited book spins a contemporary fable about individuation, freedom, art, and family politics.

But what happens when the parents pursue their true desires to the limit? What are true desires anyway? And what about children who impede their parents’ efforts to attain artistic goals? Kevin Wilson’s comic first novel, The Family Fang, turns Jung’s proclamation (and our aggrieved and rutted use of it) on its head. His spirited book spins a contemporary fable about individuation, freedom, art, and family politics.

The parents here are Caleb and Camille Fang, irrepressible performance artists who incorporated their two children, Annie and Buster, into their capers. In the present time of the story, the grown siblings now pursue their own professions, Annie as an actress, Buster as a writer of young adult novels. The narrative, a loopy string of mirthful disturbances, alternates between flashbacks to their parents’ theatrical pranks and the current, persisting antagonisms between parents and offspring.

The novel’s antic, underdoggish psyche is centered between Annie and Buster. Wilson begins things with a rapid sequence of career-damaging publicity pratfalls by Annie. Her former boyfriend, still lingering on the edges, “had written two novels that felt like movies and then started writing screenplays that felt like TV shows.” It’s an interesting line insofar as Wilson’s book strides with both cinematic verve and novelistic agility – and acknowledges its own gestures. Meanwhile, Buster injures himself on a freelance writing assignment. Mel Brooks once quipped, “Tragedy is if I cut my finger. Comedy is if I walk into an open sewer and die.” The Family Fang thereby qualifies as comedy – and death soon arises as one of its fearful preoccupations.

The novel’s antic, underdoggish psyche is centered between Annie and Buster. Wilson begins things with a rapid sequence of career-damaging publicity pratfalls by Annie. Her former boyfriend, still lingering on the edges, “had written two novels that felt like movies and then started writing screenplays that felt like TV shows.” It’s an interesting line insofar as Wilson’s book strides with both cinematic verve and novelistic agility – and acknowledges its own gestures. Meanwhile, Buster injures himself on a freelance writing assignment. Mel Brooks once quipped, “Tragedy is if I cut my finger. Comedy is if I walk into an open sewer and die.” The Family Fang thereby qualifies as comedy – and death soon arises as one of its fearful preoccupations.

But first, we witness Caleb and Camille devising an initial shock-performance in March, 1985. They call the piece “The Sound and the Fury.” It begins in a park where Annie and Buster sing six songs off-key. A crowd has gathered. She plucks a guitar’s single string and he bangs a drum. The guitar case, open before them, includes a sign that reads Our Dog Needs an Operation. Please Help us Save Him. The dog is named Mr. Cornelius. Written by Caleb, the lyric goes, “It’s a sad world. It’s unforgiving. / Kill all parents, so you can keep living.” Then their father’s voice yells out, “You’re terrible!” – dividing the crowd “into two factions. Those who wanted to save Mr. Cornelius and those who were complete and total assholes.” Later, Caleb says, “Great art is difficult” after one of his pieces fails to disturb a scene at a mall. Nevertheless, “their parents were already thinking of new ideas to create chaos that they believed the world deserved.”

But first, we witness Caleb and Camille devising an initial shock-performance in March, 1985. They call the piece “The Sound and the Fury.” It begins in a park where Annie and Buster sing six songs off-key. A crowd has gathered. She plucks a guitar’s single string and he bangs a drum. The guitar case, open before them, includes a sign that reads Our Dog Needs an Operation. Please Help us Save Him. The dog is named Mr. Cornelius. Written by Caleb, the lyric goes, “It’s a sad world. It’s unforgiving. / Kill all parents, so you can keep living.” Then their father’s voice yells out, “You’re terrible!” – dividing the crowd “into two factions. Those who wanted to save Mr. Cornelius and those who were complete and total assholes.” Later, Caleb says, “Great art is difficult” after one of his pieces fails to disturb a scene at a mall. Nevertheless, “their parents were already thinking of new ideas to create chaos that they believed the world deserved.”

When Annie and Buster win roles in their school play, Caleb and Camille conspire to create a Fang event without the children’s knowledge, injecting “the threat of upheaval … Buster and Annie the harbingers of some great disturbance.” Annie comes to resent being “an artistic prop.” If only she could attain her own identity as an actress instead of being designated as “Child A,” then “people would recognize her in the middle of a Fang event and they would ask for her autograph … She could, effectively, ruin everything for her parents.”

When Annie and Buster win roles in their school play, Caleb and Camille conspire to create a Fang event without the children’s knowledge, injecting “the threat of upheaval … Buster and Annie the harbingers of some great disturbance.” Annie comes to resent being “an artistic prop.” If only she could attain her own identity as an actress instead of being designated as “Child A,” then “people would recognize her in the middle of a Fang event and they would ask for her autograph … She could, effectively, ruin everything for her parents.”

When Annie and Buster return abashed to their Tennessee home, the novel enters a darker, more restrained phase. (At Buster’s arrival, the parents show up at the airport with bloody, bandaged wounds from a “bear attack.”) The parents may be losing their artistic edge. And then, a new, difficult struggle begins.

Episodic, briskly narrated, and overtly themed, The Family Fang recalls the snappy surface of a screenplay. It pulses with a familial pang for resolution – but surprises the reader when it arrives. It reminds me of those Jungian tales (except here, larded with comebacks and punchlines) wherein the conclusion unmasks a hidden drive and offers an unanticipated solution. Archetypes power up, then transform into actual human faces. A blithe energy keeps the novel afloat above its grave matter. Although Wilson seems to be siding with the aspirations of the children (and Buster’s style of fiction writing), he also incorporates some of the parents’ impetuousness into the novel’s tone.

Of course, Jung never intended to let anyone thrive by way of grievances, and Wilson doesn’t allow Annie and Buster to remain stuck in resentment. “The greatest and most important problems of life are all fundamentally insoluble,” wrote Jung. “They can never be solved but only outgrown.” The Family Fang freshens up that eternally wise advice.

Of course, Jung never intended to let anyone thrive by way of grievances, and Wilson doesn’t allow Annie and Buster to remain stuck in resentment. “The greatest and most important problems of life are all fundamentally insoluble,” wrote Jung. “They can never be solved but only outgrown.” The Family Fang freshens up that eternally wise advice.

[Published by Ecco Books on August 9, 2011. 310 pages, $23.95 hardcover]

Enjoyed the novel and your

Enjoyed the novel and your review. Re: “snappy surface of a screenplay,” just learned that Nicole Kidman has optioned the rights. I think she’ll make a fine Camille.

http://blogs.indiewire.com/thompsononhollywood/2011/10/28/in_the_works_oct_28/