Hypnos by René Char, translated by Mark Hutchinson (Seagull Books/University of Chicago Press)

American Pulp: How Paperbacks Brought Modernism to Main Street by Paula Rabinowitz (Princeton University Press)

Air Raid by Alexander Kluge, with an afterword by W.E. Sebald (Seagull Books/University of Chicago Press)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

René Char (1907-1988) published his first book of poems in 1928. By 1940, when he joined the French resistance, he had broken away from the Surrealists and had devised his own sound. Refusing to circulate his latest verse during the war, he wrote his Feuillets d’Hypnos between 1943-44, prose poems that speak from clandestine locations. They were published in 1946 to broad acclaim, immediately after the appearance of his first post-war poetry collection, Seuls demeurent. As I noted in a previous essay on Char, his wartime notebooks contain some of his most incisive writing about poetry.

Cid Corman’s translation of Leaves of Hypnos appeared in 1973, and selected segments of Char’s notebooks have more recently been translated by other poets. Now, Seagull Books has published a superb new translation by Mark Hutchinson called Hypnos. One instantly notices tonal differences between the Corman and Hutchinson versions – variations that have as much to do with rendering “meaning” as with how each translator regards the psyche of the dissident fighter. Corman’s phrasing accentuates a rapt, noble authority, as if a serious poet must exist on a higher plane of consciousness. Hutchinson’s locution suggests a candid manager with no time to waste on ceremony. However, there are many moments when the two translators’ approaches nearly coincide.

Cid Corman’s translation of Leaves of Hypnos appeared in 1973, and selected segments of Char’s notebooks have more recently been translated by other poets. Now, Seagull Books has published a superb new translation by Mark Hutchinson called Hypnos. One instantly notices tonal differences between the Corman and Hutchinson versions – variations that have as much to do with rendering “meaning” as with how each translator regards the psyche of the dissident fighter. Corman’s phrasing accentuates a rapt, noble authority, as if a serious poet must exist on a higher plane of consciousness. Hutchinson’s locution suggests a candid manager with no time to waste on ceremony. However, there are many moments when the two translators’ approaches nearly coincide.

Take a look at these renditions below of segment 51 of Hypnos. First the Corman:

“Uproot him from his native land. Replant him in soil, presumed harmonious with the future, allowing for an incomplete success.. Make him touch progress sensorially. That’s the secret of my ‘skillfulness.’”

Then, the Hutchinson:

“Uproot them from their native earth. Set them down in what you presume to be the harmonious soil of the future, bearing in mind that success can only ever be partial. Have them progress through the senses. That is the secret of my ‘skill.’”

In my ear, Hutchinson’s more spoken version sustains the sense of risk in the speaker even before one arrives at the questioned skillfulness. Responsible for “progress,” he refers to those comrades he commands, not to an individual. As Hutchinson’s translation of Hypnos unfolds, Char emerges as a remarkable leader, both committed and cerebral, striving and pausing:

132

It seems that the imagination which in varying degrees haunts the mind of every living creature is quick to abandon it when the latter has only the ‘impossible’ and the ‘inaccessible’ as the ultimate mission to propose. Poetry, it has to be allowed, is not everywhere sovereign.

Char’s reputation was so great that in late 1944 he was asked to sit on the jury of a high court set to try members of the Vichy regime. He declined, as Hutchinson notes in his introduction, because Char “was not only oppressed by the atmosphere of denunciations and reprisals but also tormented by doubts and misgivings about the cost to himself and to others of his activities in the Maquis.” Char wanted Hypnos to be rushed into print after the war’s end because he believed its provenance should be considered during the making of the country’s new constitution. This aim in itself says much about Char and perhaps also about the influence of literature at that moment. His publisher, Gallimard, arranged to have a have a large segment quickly published in a journal. Char’s collaborative editor at the press was Raymond Queneau.

Char’s reputation was so great that in late 1944 he was asked to sit on the jury of a high court set to try members of the Vichy regime. He declined, as Hutchinson notes in his introduction, because Char “was not only oppressed by the atmosphere of denunciations and reprisals but also tormented by doubts and misgivings about the cost to himself and to others of his activities in the Maquis.” Char wanted Hypnos to be rushed into print after the war’s end because he believed its provenance should be considered during the making of the country’s new constitution. This aim in itself says much about Char and perhaps also about the influence of literature at that moment. His publisher, Gallimard, arranged to have a have a large segment quickly published in a journal. Char’s collaborative editor at the press was Raymond Queneau.

[Published September 15, 2014. 72 pages, $21.00 hardcover]

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

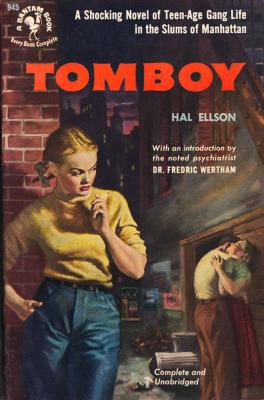

Paula Rabinowitz, an English professor at the University of Minnesota, is hardly the first scholar to write about the tradition of pulp paperbacks in America. But in American Pulp, she opens a unique view to the phenomenon. “What is pulp?” she asks. “Steamy fiction? Sleazy magazines? Cheap paper? Or might it be a technology, a vehicle that once brought desire – for sex, for violence – into the open in cheap, accessible form? Or, and this is the question that motivates this book, might it be part of a larger process by which modernism itself, as high literature and art but also as a mass consumer practice, spread across America?”

Paula Rabinowitz, an English professor at the University of Minnesota, is hardly the first scholar to write about the tradition of pulp paperbacks in America. But in American Pulp, she opens a unique view to the phenomenon. “What is pulp?” she asks. “Steamy fiction? Sleazy magazines? Cheap paper? Or might it be a technology, a vehicle that once brought desire – for sex, for violence – into the open in cheap, accessible form? Or, and this is the question that motivates this book, might it be part of a larger process by which modernism itself, as high literature and art but also as a mass consumer practice, spread across America?”

A few revealing facts clinch her premise almost immediately. For instance, consider that the first time the work of Jorge Luis Borges appeared in print in America, it was in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. All sorts of literature could be pulped, from the classics to racy new novels pursued by the censors. Faulkner’s The Wild Palms was promoted as “a haunting story of lovers confronted by rthe relentless pressures of a morality which no one can defy without disaster.”

For Rabinowitz, pulp is personal. “I cannot remember when I began amassing pulp,” she writes. “They were the books my parents owned, bought to be read because they were cheap. I took some of them with me when I left home as a teenager … Then I began to consciously seek out some of these pulp books – though not any one would do. Don’t ask me why, but I was interested only in the pulp versions of ‘great literature’ … New American Library was my brand.”

In pulp lit, Rabinowitz perceives “keys to demotic reading, an experience of literature that traverses many social distinctions.” It is partially through these texts, often initially attracted by cover art, that Americans first conceptualized the notion of diversity – sexual, racial, social, economic. The first popular treatments of GLBT life appeared there. “A lowly yet somehow revered object, the paperback book exemplifies a modernist form of multimedia in which text, image, and material come together as spectacle to attract and enthrall recipient, its audience, its reader,” she says. Such media moves fluidly from personal to public places, from the revolving book kiosk at the drugstore to the bedroom. “Pulps confused who got to read what and where this would occur.”

In pulp lit, Rabinowitz perceives “keys to demotic reading, an experience of literature that traverses many social distinctions.” It is partially through these texts, often initially attracted by cover art, that Americans first conceptualized the notion of diversity – sexual, racial, social, economic. The first popular treatments of GLBT life appeared there. “A lowly yet somehow revered object, the paperback book exemplifies a modernist form of multimedia in which text, image, and material come together as spectacle to attract and enthrall recipient, its audience, its reader,” she says. Such media moves fluidly from personal to public places, from the revolving book kiosk at the drugstore to the bedroom. “Pulps confused who got to read what and where this would occur.”

After a review of the “biography” of the pulp paperback, Rabinowitz considers the underlying significance of pulp’s “slangy interface,” a product designed to create a mash-up of the author, the masses, and the provocative message, or as McLuhan put it, “This need to interface, to confront environments with a certain antisocial power …” She goes on to trace the emergence of Richard Wright’s work when he was “still an aspiring novelist in Chicago, collecting hoards of crime stories from pulps and tabloids, then drawing on these to write Native Son and 12 Million Black Voices. It was Wright who had said that “True Story magazines were revolutionary documents when they fell into the hands of the folk Southern Negroes. They instilled restlessness, a capacity for credulity, and an eagerness to move forward to new experiences.”

Rabinowitz devotes chapters to the exposure of GI’s to paperbacks, the scandalous novels of Ann Petry (the racial, ethnic, and sexual obsessions of small-town white America), Borges and pulps, “uncovering lesbian pulp,” the portrayals of the Holocaust and the new age of The Bomb, and censorship. She writes with briskness and acuity. The historical richness of the material is leavened by a lively, broadminded, and humane sense of her culture. But most important, she writes with affection for the profound effects of her subject. Her own early responses to the genre are palpable: “The paperback, indeed, literature tout court, is suffused with desire and love, of and for sisters and parents, imagined lovers, real boyfriends. It is a token and expression of what cannot be contained, a tangible object that, in its totality, offers entrance into the infinitude of time and memory and all one might want collapsed into the hours spent alone with it.”

Rabinowitz devotes chapters to the exposure of GI’s to paperbacks, the scandalous novels of Ann Petry (the racial, ethnic, and sexual obsessions of small-town white America), Borges and pulps, “uncovering lesbian pulp,” the portrayals of the Holocaust and the new age of The Bomb, and censorship. She writes with briskness and acuity. The historical richness of the material is leavened by a lively, broadminded, and humane sense of her culture. But most important, she writes with affection for the profound effects of her subject. Her own early responses to the genre are palpable: “The paperback, indeed, literature tout court, is suffused with desire and love, of and for sisters and parents, imagined lovers, real boyfriends. It is a token and expression of what cannot be contained, a tangible object that, in its totality, offers entrance into the infinitude of time and memory and all one might want collapsed into the hours spent alone with it.”

[Published November 5, 2014. 390 pages, $29.95 hardcover. Includes 22 pages (center inserted) of color artwork. There are black and white images throughout the text.]

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

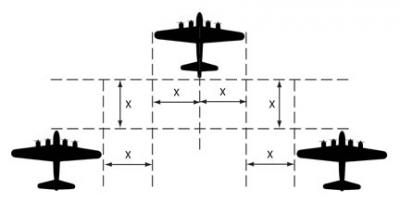

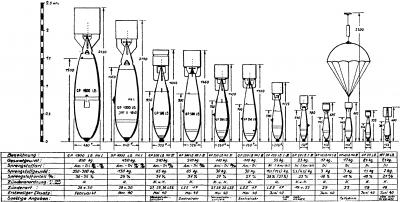

During the late morning of April 8, 1945, a formation of American B-17’s droned above the German town of Halberstadt in Saxony. Unable to drop their munitions on the oil storage depot at Stassfurt due to cloud cover, the squadron proceeded to the alternate target at Halberstadt, home to 64,000 inhabitants. There was an airfield just to the south of town, and an aircraft wing construction site four miles away in Langenstein. But Halberstadt itself had no military significance and Germany would surrender one month later.

Alexander Kluge was thirteen years old when he witnessed the destruction of his birthplace. In 1977, he published Der Luftangriff auf Halberstadt am 8. April 1945, an unconventional account of the catastrophe. Six years ago, his publisher reissued the book with seventeen additional related pieces, and now Seagull Books has published the first English version of the expanded edition entitled Air Raid, translated by Martin Chalmers, a Glasgow-based writer.

Alexander Kluge was thirteen years old when he witnessed the destruction of his birthplace. In 1977, he published Der Luftangriff auf Halberstadt am 8. April 1945, an unconventional account of the catastrophe. Six years ago, his publisher reissued the book with seventeen additional related pieces, and now Seagull Books has published the first English version of the expanded edition entitled Air Raid, translated by Martin Chalmers, a Glasgow-based writer.

The first section, “The Air Raid on Halberstadt on 8 April 1945,” comprises documentary and archival materials. An unnamed, flat-voiced narrator begins the first segment, a restrained description of the movements of Frau Schrader, the manager of the local cinema, who survives the bombing of the structure and makes her way across the devastated town. Then, the story of the arrest of an “unknown photographer” – including six of his crude black and white images – suspected of espionage but then freed. Next, Frau Arnold and Frau Zacke, are posted in a church bell tower as air raid watchers:

“Frau Zacke does not want to ‘burn up’ on the stone ledge of the tower gallery. She nudges her colleague, grabs a folding chair, binoculars, walkie-talkie, and runs into the tower and down the wooden stairs. Frau Arnolds clatters down behind her. A powerful draught or storm wind presses the women against the railing. As they go Frau Zacke shouts into the radio: ‘Church is burning. On our way.’ The substructure of the stairs slips away under their running feet right through a column of flame and crashes onto the tower foundation. Frau Arnold, lying under burning beams, doesn’t move, doesn’t respond to the calls of Frau Zacke, whose thigh is broken.”

In a 2012 interview, Martin Chalmers describes Kluge’s tone as “a necessary dispassion combined with an underlying emotional response.” An accomplished filmmaker as well as a novelist, Kluge was trained as a lawyer and studied cultural theory with Theodor Adorno. An attorney’s reserve and gravitas are evident throughout his work. The harnessed energy is incorporated in various forms, again per Chalmers, “anecdote, incident, item, quotation, adaptation, illustration, and novels in pill form.” In Air Raid, one voice is followed by another – the testimonies of survivors, observations of reporters, explanations by American officers.

In a 2012 interview, Martin Chalmers describes Kluge’s tone as “a necessary dispassion combined with an underlying emotional response.” An accomplished filmmaker as well as a novelist, Kluge was trained as a lawyer and studied cultural theory with Theodor Adorno. An attorney’s reserve and gravitas are evident throughout his work. The harnessed energy is incorporated in various forms, again per Chalmers, “anecdote, incident, item, quotation, adaptation, illustration, and novels in pill form.” In Air Raid, one voice is followed by another – the testimonies of survivors, observations of reporters, explanations by American officers.

Quoting from a transcript of a conversation between a Swiss journalist and an American lieutenant general, Kluge’s chilly narrator considers the American Flying Fortresses as “factories” whose rationalized production must be expended, in this case to terrify and kill through carpet bombing. The reporter asks: What would the advance pilots have done if they had seen a man waving a white flag from the church steeple? The officer responds, “Who would want to take on the responsibility for our heavily laden lame ducks, just because there was a white flag somewhere? The merchandise had to be dropped on the town. It’s expensive stuff. And you can’t drop it on the hills or open country after it’s been produced with so much labor power at home. What, in your opinion, should be in the success report which has to go to senior commanders?”

W. E. Sebald’s incisive afterword focuses on the ways Kluge’s multi-genre/-material forms empower his idiosyncratic approach to telling history. Sebald repeats Brecht’s notion that “human beings learn as much from catastrophes as laboratory rabbits do from biology texts,” and asserts that “the learning process takes place subsequently – that is the raison d’être of Kluge’s text compiled 30 years after the event – and presents the only possibility of directing the hopes and wishes arising in human beings towards the anticipation of a future that is not already occupied by fear resulting from repressed experience.” Both Sebald and Kluge operate through “a critical dialectic between present and past,” an echo here of Walter Benjamin.

W. E. Sebald’s incisive afterword focuses on the ways Kluge’s multi-genre/-material forms empower his idiosyncratic approach to telling history. Sebald repeats Brecht’s notion that “human beings learn as much from catastrophes as laboratory rabbits do from biology texts,” and asserts that “the learning process takes place subsequently – that is the raison d’être of Kluge’s text compiled 30 years after the event – and presents the only possibility of directing the hopes and wishes arising in human beings towards the anticipation of a future that is not already occupied by fear resulting from repressed experience.” Both Sebald and Kluge operate through “a critical dialectic between present and past,” an echo here of Walter Benjamin.

Retrospective historiography of the conventional kind does not suffice because, Kluge says, people “take revenge against reality” when it fails to behave as they wish. In an interview with Gary Indiana in Bomb, Kluge said, “The media industry is realistic in telling fiction, and the construction of reality founded on this basis can only lie. This is one of the reasons why history isn’t realistic: it’s not documentary, it’s not genuine, and it’s not necessary.”

Retrospective historiography of the conventional kind does not suffice because, Kluge says, people “take revenge against reality” when it fails to behave as they wish. In an interview with Gary Indiana in Bomb, Kluge said, “The media industry is realistic in telling fiction, and the construction of reality founded on this basis can only lie. This is one of the reasons why history isn’t realistic: it’s not documentary, it’s not genuine, and it’s not necessary.”

[Published November 10, 2014. 138 pages, 42 black & white photographs and diagrams, $21.00 hardcover]