Jay Parini’s biography of Gore Vidal, Empire of Self, is an entertaining narrative, but midway through the book I shifted over to YouTube to watch Vidal in action. He made himself so visible that one can’t help but indulge. I watched the 1995 BBC documentary on Vidal, largely the product of its then seventy-year old subject. The camera follows as he narrates his life, including a return to Merrywood, the mansion on the Potomac that had belonged to Hugh Auchincloss, the affluent stockbroker his mother Nina married immediately after divorcing Gene Vidal.

James Merrill once remarked, “Gore sucked all the air out of any room he entered. You couldn’t breathe in his presence.” But for the film, Vidal projects an authentic weariness, fundamental to the man. In one scene, he sits down heavily at the top of the stairway where he, as a ten-year old kid, had discovered his distraught, alcoholic mother lying in her dressing gown on the morning after her wedding night to Hugh. She asked the boy, “Would you like it if I went back to your father?” He learned early about the impermanence and unreliability of affections.

James Merrill once remarked, “Gore sucked all the air out of any room he entered. You couldn’t breathe in his presence.” But for the film, Vidal projects an authentic weariness, fundamental to the man. In one scene, he sits down heavily at the top of the stairway where he, as a ten-year old kid, had discovered his distraught, alcoholic mother lying in her dressing gown on the morning after her wedding night to Hugh. She asked the boy, “Would you like it if I went back to your father?” He learned early about the impermanence and unreliability of affections.

“An artist needs not so much an audience, as to feel a need to answer, a promise to respond,” writes Robert Pinsky in an essay. One reason to read a literary biography is to sense the source of the promise and the shape of the response. What drives a writer to keep answering, and to what? Is it a promise, a compulsion, or both? Parini’s spry biography compels the reader to ask these questions about the writer described by the BBC as “America’s greatest living man of letters.” His output over a lifetime included 25 novels, two plays, 200 essays, a memoir, teleplays and screenplays. By age 25, he had already published four novels. His third, The City and the Pillar (1948), implied his coming out as gay – though as Parini says, “He certainly liked the idea of being bisexual, as the notion of being exclusively gay had very little appeal, pushing him too far into the margins of society.”

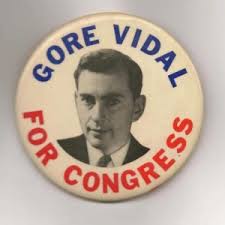

“Empire of self” plainly indicates Parini’s focus on Vidal’s blob-like expansion of himself into the culture, from the graphomania of novel writing to his many appearances on talk shows, and from his nose-tweaking of America’s sexual and moral codes to his failed campaigns for political office. “I have no wish to do more than describe a man I admired and valued as a friend,” writes Parini, and for much of the book we simply follow Vidal’s pivoting from project to project, place to place. Beneath the surface of Vidal’s strivings, “he had a fragile sense of his own reality, though he would erect a vast empire of self on this slender foundation.” While arguing for the welfare of ordinary Americans, “he had no wish to mingle with them, preferring suites in five-star hotels and good restaurants.” He spoke with a patrician accent and pursued the elite while skewering them in his novels. He was an autodidact who chose to write a novel at age 19 while his friends went off to Harvard and Princeton.

“Empire of self” plainly indicates Parini’s focus on Vidal’s blob-like expansion of himself into the culture, from the graphomania of novel writing to his many appearances on talk shows, and from his nose-tweaking of America’s sexual and moral codes to his failed campaigns for political office. “I have no wish to do more than describe a man I admired and valued as a friend,” writes Parini, and for much of the book we simply follow Vidal’s pivoting from project to project, place to place. Beneath the surface of Vidal’s strivings, “he had a fragile sense of his own reality, though he would erect a vast empire of self on this slender foundation.” While arguing for the welfare of ordinary Americans, “he had no wish to mingle with them, preferring suites in five-star hotels and good restaurants.” He spoke with a patrician accent and pursued the elite while skewering them in his novels. He was an autodidact who chose to write a novel at age 19 while his friends went off to Harvard and Princeton.

In between his chapters, Parini inserts “suggestive vignettes” of moments he spent with Vidal who was aware that Parini might one day write this biography. (Vidal didn’t drive; they seem to have spent most of their time together in Parini‘s car.) “He could be cantankerous, testy, ill-mannered, a terrible snob, a drunken bore,” Parini writes. “On top of which he had, as Jason Epstein notes, terribly thin skin, and believed a vigorous offense was the best defense. He struck back reflexively at those who criticized him. And he never forgot a slight, however minor.” Parini frequently refers to Vidal as a “narcissist”– and though I rarely find the term useful, I understand Parini’s usage: “His narcissism skewed his daily life in unattractive ways, as he sought reinforcement wherever he could. His imperial self demanded obeisance and agreement from those around him.” Still, Parini insists that “a biographer is not a judge” — while gathering the judgments of many of Vidal’s closest friends and generously assessing Vidal’s novels.

There were the loveless hallways of his family (Vidal later revived a relationship with his father but banished the mother) and the power-driven hallways of the Capitol. Born in 1925, Vidal spent the most stable part of his childhood in Washington D.C. at the side of his maternal grandfather, Thomas Pryor Gore, a senator from Oklahoma best known for his anti-Roosevelt politics and his blindness. Having accompanied his grandfather to the Senate chamber, the grandson long regarded the man as a model in political thinking. There was also a teenaged love affair with Jimmy Trimble, a classmate at St. Alban’s who was killed during World War II – but Parini wisely speculates that Jimmy may have come to stand for a long lost part of Vidal himself. Vidal evoked his hallowed, once-in-a-lifetime relationship with Jimmy whenever he recollected his youth. “Romantic love, as Americans conceive it, does not exist,” he told Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes in 1975. “I’m devoted to promiscuity.”

There were the loveless hallways of his family (Vidal later revived a relationship with his father but banished the mother) and the power-driven hallways of the Capitol. Born in 1925, Vidal spent the most stable part of his childhood in Washington D.C. at the side of his maternal grandfather, Thomas Pryor Gore, a senator from Oklahoma best known for his anti-Roosevelt politics and his blindness. Having accompanied his grandfather to the Senate chamber, the grandson long regarded the man as a model in political thinking. There was also a teenaged love affair with Jimmy Trimble, a classmate at St. Alban’s who was killed during World War II – but Parini wisely speculates that Jimmy may have come to stand for a long lost part of Vidal himself. Vidal evoked his hallowed, once-in-a-lifetime relationship with Jimmy whenever he recollected his youth. “Romantic love, as Americans conceive it, does not exist,” he told Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes in 1975. “I’m devoted to promiscuity.”

His grandfather’s isolationist politics triggered Vidal’s anti-imperialist critiques. “The world, in his view, had fallen away from a beautiful moment at the inception of the American republic,” Parini writes, “when – briefly – the ideals of life and liberty seemed to prevail.” Short-lived idyllic beginnings yield to endless malaise. With shrewd timing, Vidal produced satirical novels, essays and plays that Americans wanted to read and see. His antagonistic but poised arguments could enrage his enemies – and so again, I revert to YouTube to watch him joust with William F. Buckley on the Vietnam War, an argument that leads to Buckley calling him a “queer” and losing his famous reptilian composure.

One may weigh the possibility that Vidal needed an adoring audience more than a need to answer to it – but he answered so frequently that such a conclusion is hard to reach. He may have applied too many coats of irony to his work, and like a politician, he behaved in public as one who never gives the game away. Vidal said he was a young man forever, skipped middle age, and suddenly became an old man. His old age was a case of terminal truculence, but he saw the irony in the life he pursued. Although he bristled at reviewers’ failures to be consistent in praising his work, he didn’t exclude himself from his peers when he said, “American writers want not to be good but to be great, and so are neither.” He knew he had a talent for screenplays and dialogue, like Wilder and Steinbeck — but he qualified this by saying, “We speak now not of genius but of versatility.”

One may weigh the possibility that Vidal needed an adoring audience more than a need to answer to it – but he answered so frequently that such a conclusion is hard to reach. He may have applied too many coats of irony to his work, and like a politician, he behaved in public as one who never gives the game away. Vidal said he was a young man forever, skipped middle age, and suddenly became an old man. His old age was a case of terminal truculence, but he saw the irony in the life he pursued. Although he bristled at reviewers’ failures to be consistent in praising his work, he didn’t exclude himself from his peers when he said, “American writers want not to be good but to be great, and so are neither.” He knew he had a talent for screenplays and dialogue, like Wilder and Steinbeck — but he qualified this by saying, “We speak now not of genius but of versatility.”

As divided as his subject, this biography is in part an homage to the long, stubborn deployment of Vidal’s intellect and élan – and a tender take-down. Parini leaves the reader well-equipped in the vital position of imagining the inner man.

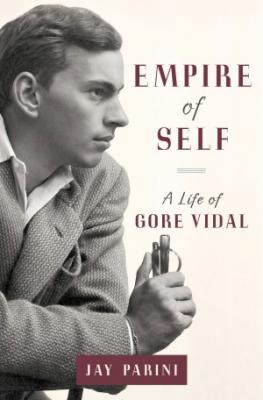

[Published by Doubleday on October 13, 2015. 480 pages, $35.00 hardcover]