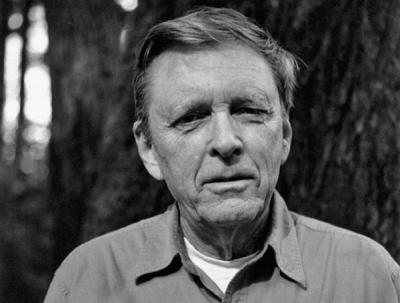

In 2011, the Yale University Art Gallery published The Place We Live, a three-volume retrospective of Robert Adams’ photography. In a brief introduction, Adams begins by quoting three poets. First, Hugh MacDiarmid: “It is a frenzied and chaotic age, like a growth of weeds on the site of a demolished building.” Then, Anna Akhmatova: “The miraculous comes so close to the ruined, dirty houses.” There is also a single line by Hölderlin: “To live is to defend a form.” It had been Adams’ early intention to teach literature. He received his Ph.D. in English at USC in 1965 and joined the faculty at Colorado College. By 1970 he had become fully committed to photography, but his writings and published interviews often include lines by poets. Like the prose of John Berger, Adams’ brief and incisive essays, honoring the mystery of images and the commitment to keep making them, also advocate for passionately held social and artistic values.

Conceived with a stark but empathic exactitude, his photographs and essays have offered a five decades-long opportunity for us to ask: What is beauty? “Beauty that concerns me is that of form,” he writes in “Truth and Landscape,” an essay in Beauty in Photography (Aperture, 1996). He continues, “Beauty is, in my view, a synonym for the coherence and structure underlying life … Why is Form beautiful? Because, I think, it helps us meet our worst fear, the suspicion that life may be chaos and that therefore our suffering is without meaning.” Quoting William Carlos Williams’ use of the term splendor to describe the beautiful, Adams then goes further: “The Form toward which art points is of an incontrovertible brilliance, but it is also far too intense to examine directly. We are compelled to understand Form by its fragmentary reflection in the daily objects around us: art will never fully define light.”

Conceived with a stark but empathic exactitude, his photographs and essays have offered a five decades-long opportunity for us to ask: What is beauty? “Beauty that concerns me is that of form,” he writes in “Truth and Landscape,” an essay in Beauty in Photography (Aperture, 1996). He continues, “Beauty is, in my view, a synonym for the coherence and structure underlying life … Why is Form beautiful? Because, I think, it helps us meet our worst fear, the suspicion that life may be chaos and that therefore our suffering is without meaning.” Quoting William Carlos Williams’ use of the term splendor to describe the beautiful, Adams then goes further: “The Form toward which art points is of an incontrovertible brilliance, but it is also far too intense to examine directly. We are compelled to understand Form by its fragmentary reflection in the daily objects around us: art will never fully define light.”

For Adams, natural light is not only always perfect, but of such a power that it can integrate the tension between opposites in our visual field. As America’s most notable photographer of the modern West, Adams advocates for the proper use of land, conservation of resources, and the lessening of pollution. But in his art, everything seen is included within the frame of beauty. About pictures taken in Denver during the 1970’s, he writes in The Place We Live, “New building had, it is true, begun to change some of the geography, but the light was clean enough to disinfect car agencies and cheap bungalows … if beauty were to be discovered in Denver, it had to be on the basis of a radical faith in inclusion.” Born in 1937, Adams contracted polio at age twelve but managed to recover — an experience that perhaps inspired in him a search for reconciliation at the site of ravages.

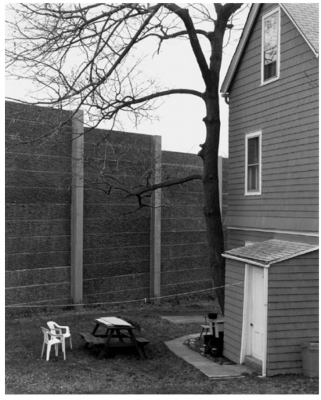

Adams’ 1994 essay collection Why People Photograph includes a section titled “What Can Help.” Clearly, he has felt that we need more and more to help us because now we have Art Can Help, tersely illuminating commentary on works by 28 photographers (though he begins with a look at Edward Hopper’s “Early Sunday Morning” – “Light explains nothing about meaning, but for Hopper it was the basis of a lifetime’s faith”). Next come four paragraphs on Richard Rothman’s photograph, “Home With Sound Wall, N.J.” (1995):

Richard Rothman’s picture lets us live with our disappointment, just barely. It suggests poet Stephen Berg’s description of a cantor’s prayer – “inconsolable praise.”

Richard Rothman’s picture lets us live with our disappointment, just barely. It suggests poet Stephen Berg’s description of a cantor’s prayer – “inconsolable praise.”

The photograph helps us in part exactly because it does acknowledge harrowing fact – it does not lie. The sound wall next to the expressway is savage – dark, not fully effective, and out of human scale. The picnic area, if that is what the table implies we should call it, is desolate: there is not a decorative shrub to be seen, and the mass-produced plastic chairs confirm that little here is particular to individual dreams.

Against the sky, however, there are branches of a tree. They are leafless – we do not know whether it is winter or if the tree is dead from traffic fumes – but the shape is organic. The branches might be visited by living birds.

Few artists care enough about us to risk our alienation by a picture so taut with despair and fragile possibility.

Ken Abbott’s 1989 photo “Golf Course Under Construction, East of Boulder, Colorado,” triggers this observation: “Form in a picture is justified by our experience of wholeness (coherence) in life, and if we are to be convincingly reminded by art of such experience then the shape in art has to be believably tentative, as fragile as meaning seems to be in life, as problematic even as the future is for those cottonwood shoots there on the far side of the creek.” Adams’ sentences force one to slow down and listen. He has as much to say about artists and poets as to them – especially when reminding us that our best work will be “believably tentative.”

In 1975, his work was shown for the first time at the George Eastman House in Rochester beside prints by Stephen Shore, Frank Gohlke, Lewis Baltz and others. Since then, Adams has been known as a generous supporter of his contemporaries’’ work (“Colleagues” is one of the sections of his old essay “What Can Help”.) In Art Can Help, he comments on images by Gohlke, Adams’ mentor John Szarkowski, Judith Roy Ross, Emmet Gowin, Terri Weifenbach, Garry Winogrand, Mary Peck, Leo Rubinfien, Anthony Hernandez, Mark Ruwedel and others – as well as the classic work of Dorothea Lange. There are also words from Czeslaw Milosz, Virginia Woolf, Stanley Elkin, Etta James, William Stafford, Richard Wilbur, George Herbert, Loren Eiseley, Stephen Spender, and Wendell Berry.

In 1975, his work was shown for the first time at the George Eastman House in Rochester beside prints by Stephen Shore, Frank Gohlke, Lewis Baltz and others. Since then, Adams has been known as a generous supporter of his contemporaries’’ work (“Colleagues” is one of the sections of his old essay “What Can Help”.) In Art Can Help, he comments on images by Gohlke, Adams’ mentor John Szarkowski, Judith Roy Ross, Emmet Gowin, Terri Weifenbach, Garry Winogrand, Mary Peck, Leo Rubinfien, Anthony Hernandez, Mark Ruwedel and others – as well as the classic work of Dorothea Lange. There are also words from Czeslaw Milosz, Virginia Woolf, Stanley Elkin, Etta James, William Stafford, Richard Wilbur, George Herbert, Loren Eiseley, Stephen Spender, and Wendell Berry.

While pointing out that the subject of a photo or poem does not in itself constitute artistic value, he insists that “if there is no clarifying reference out to significant life beyond the frame” then the term art “seems to me unearned.” In the past, he has been critical of work that is “free of any conceptual content … form purely of ordered sensation.” Paintings by Pollock and Stella are for him “minor pleasures.” In the introduction to Art Can Help, he writes, “The emptiness of material by Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, for example, is born of cynicism and predictive of nihilism.” If Adams worries in his afterword that “It is difficult to believe we have a future,” his antidote is to “be coherent about intuition and hope.” To not turn away from what is there, especially the tragic nature of human life. If in his and his colleagues’ pictures there is a confrontation with suffering and darkness, then there is also “something for which there are only inadequate words. The best writers have nonetheless tried to say what it is, and Marilynne Robinson is among them, speaking in the novel Lila of “weariness … as beautiful as light.”

[Published by Yale University Press on September 19, 2017. 92 pages, 35 color and b&w plates, $25.00 hardcover]