The Argentinian writer César Aira hypothesizes that the birth of literature occurred with “the first poem or the first story as a mythical description or interpretation of a drawing or a statue.” A shaky proposition, he admits – though his own lifelong impulse to find “inspiration, stimulation, means, and themes in painting” has been anything but undependable. “The mediation of images imposes a distance,” he writes in On Contemporary Art, “and that distance opens up a space in which words can resonate and multiply their expression beyond what is utilitarian.”

Aira’s new book arrived in my mailbox while I was preparing to write about John Yau’s eighteenth collection of poems, Bijoux in the Dark. The drive to keep reentering that imposed distance between one’s eye and an artwork instantly evoked Yau’s long career as art critic. Ekphrastic poems, those written about works of art, are occasional ventures for most poets. But Yau dwells in that speculative space – and Aira’s phrase “expression beyond what is utilitarian” suggests the provenance and practice of Yau’s poetic ethos.

Written in the Shadow of Francis Bacon’s Self-Portrait Triptych (1985-86)

1.

I haven’t got a clue

as to why

I woke up

in these clothes

someone else’s

cheaply manufactured

persona

bag of discounted

egg noodles

in one hand

throttling

dream’s sweet neck

with other

2.

I still don’t understand

how my face

ended up in the painting

that you are laughing at

while the rest of me

was tossed in the trash

Not even the bird

that whispers in my ear

knows the answer

to this ridiculous riddle

3.

And I still have no idea

why I am straddling

a broken tricycle

waiting for snow

to obliterate

this poem

Nor do I understand why

my declarations of love

are considered

unwarranted distractions

an annoying mosquito

full of venom

it doesn’t know it is carrying

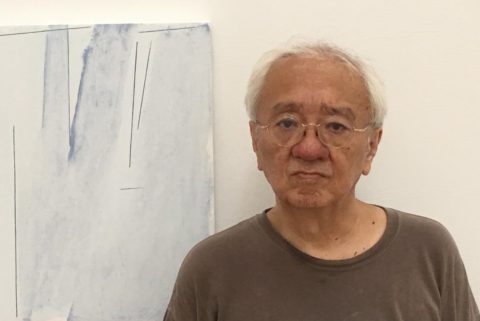

Born in 1950 and awakened to poetry at age 15 by encountering Robert Lowell’s For The Union Dead, and soon thereafter, Robert Kelly’s anthology A Controversy of Poets, Yau discovered Ashbery, O’Hara, and Spicer. A conspicuously youthful customer at the Grolier Poetry Book Shop in Harvard Square, Yau wrote his first poems as a high school freshman. At the same time, he was already an avid gazer of art. In a lively interview published in Jarrett Earnest’s What It Means To Write About Art, Yau recalls his many visits to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. The father of his closest friend was John Way, “an abstract painter, and he painted in the living room of their apartment in Beacon Hill. So at seven, eight, nine, I see a man making abstract paintings in his living room, like it is a normal activity.”

Born in 1950 and awakened to poetry at age 15 by encountering Robert Lowell’s For The Union Dead, and soon thereafter, Robert Kelly’s anthology A Controversy of Poets, Yau discovered Ashbery, O’Hara, and Spicer. A conspicuously youthful customer at the Grolier Poetry Book Shop in Harvard Square, Yau wrote his first poems as a high school freshman. At the same time, he was already an avid gazer of art. In a lively interview published in Jarrett Earnest’s What It Means To Write About Art, Yau recalls his many visits to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. The father of his closest friend was John Way, “an abstract painter, and he painted in the living room of their apartment in Beacon Hill. So at seven, eight, nine, I see a man making abstract paintings in his living room, like it is a normal activity.”

At age 20, after transferring from Boston University to Bard where Kelly was teaching, Yau learned that Ashbery and O’Hara wrote art reviews. In 1974, he applied to the MFA writing program at Brooklyn College to study under Ashbery. One day, the phone rang: Ashbery, with news that his application had been accepted. By 1977, Yau was writing for Art in America. He says, “I remember [Ashbery] brought me to an opening and introduced me to David Hockney. I was, like, twenty-seven and meeting all these people … There was a moment where I actually told John, I can’t write about any of the people you’ve written about. I have to find out everything on my own.”

Yau’s essay “The Poet as Art Critic” (2005), collected in The Passionate Spectator, describes the ways in which Ashbery’s and O’Hara’s art criticism differed from that produced by those with academic training in art history and theory-driven techniques. But more illuminating to Yau’s poetry is his selection of excerpts from Ashbery’s art writing and its frequent references to the work and thinking of poets. About Ashbery’s remarks on director Robert Bresson, Yau writes:

“Already masterful in his ability to shift tones and focus, Ashbery has consciously rejected transparency, received notions of realism in poetry, and confession, all of which were (and still are) believed to be allegorical narratives that naturally culminate in revelation, universal truth, or epiphany. All too often, these states of illuminated insight are familiar and border on cliche. The revelation is not something the poet discovers in the process of writing, but is something he or she already possesses, and must figure out how to package. Such poems are full of detachable symbols and images, triggers that set of the reader’s sympathetic Pavlovian response.”

“Already masterful in his ability to shift tones and focus, Ashbery has consciously rejected transparency, received notions of realism in poetry, and confession, all of which were (and still are) believed to be allegorical narratives that naturally culminate in revelation, universal truth, or epiphany. All too often, these states of illuminated insight are familiar and border on cliche. The revelation is not something the poet discovers in the process of writing, but is something he or she already possesses, and must figure out how to package. Such poems are full of detachable symbols and images, triggers that set of the reader’s sympathetic Pavlovian response.”

“How do you proselytize without becoming proscriptive, dogmatic, or polemical?” Yau asks in reference to the hierarchical judgments of some art critics – but he could have been asking it about some poets as well. His poetry takes root in Ashbery’s own proscription for the submergence of the self-crediting personality. But as “Written in the Shadow of Francis Bacon’s Triptych” shows, Yau is keenly interested in the assertions and vagaries of identity – not the life-facts and value of identity, but its fluctuations, accretions and devolutions. Unlike Ashbery, Yau speaks to a field of relations – that is, he seems to maintain that such relations exist and are worth undertaking, if sometimes dubiously. “The only thing that holds us together are the missives we send to each other,” he writes in “Firefly Promises,” the fourth part of which reads:

4.

I am copying down what I am being told to write. It is not a voice I hear, yours or mine or anyone else’s, but the space between words that seems to fill with other words, other indications, hints or hums – a kind of music that words cannot accompany, falling away from their small handles on the world, like leaves on a windy day.

I am copying down what I am being told to write, but I keep thinking these are my words, not someone else’s, that I am thinking and saying and sending to you. And yet it’s not you that I am writing to, is it? It is my idea of you, my dream, illusion or glimpse. A string of silhouettes.

This can only mean that this is my ode to failing to write a poem worthy of your attention. Am I extolling you or extirpating words that are poor exposures of the quandary of pronouns you tell me constitute some of the parameters of your inexhaustible inferno?

Is this what it means to fall out of the unauthorized sky? Is this what it means to be a feather borne by the wind, or a cloud of thwarted eagerness? What brought us to this ocean of loneliness in which we can hear each other swimming in the distance?

Diverting, mocking, amusing, critical, cool and oddly companionable — Yau’s poems – in their wide range of materials, attitudes, surprises, and quipping address – appeal to and privilege the reader’s experience, not conclusions. The world here is both recognizable and transparent. The political is here, too, but an enigma shows through it. Yau grew up in Lynn, Massachusetts, fluently speaking two languages. His father, whose mother was English, attended Catholic missionary school in Shanghai. His mother studied English in China and was fluent in French. The family also conversed in a Shanghai dialect. All of this is present, somewhere, in “Music from Childhood” which begins:

You grow up hearing two languages. Neither fits your fits

Your mother informs you “moon” means “window to another world”

You begin to hear words mourn the sounds buried inside their mouths

A row of yellow windows and a painting of them

There is no narrative armature in “Music From Childhood” – instead one finds a mottled memory of wonderment about language and languages, the residue of the musing solitude of a fanciful child. The situation of the poem is vivid and moving because the mind within it moves freely between recollection and repetition, the past and the present moment of phrase-making, with no flattering of the reader’s sensibilities and opinions. Yet I don’t completely concur that Yau’s poetry is entirely mission-less and “beyond the utilitarian.” In fact, his poems rigorously teach about our inability to envision the world as anything other than indefinite — or on the flip side, the poems embody our spectacular ability to query the definite nature of a world (or an art work) that we can’t definitively describe. The ethics of aesthetics tell us to base our care for each other on an affection for the density of experience itself.

Bijoux in the Dark is filled with nods to American culture and the moment’s urgencies. There’s a lot of work here, some 58 pieces, taking various forms. The fifth section, “Bijoux in the Dark,” includes flash fictions and numbered prose pieces that riff on cinema, together comprising an entire catalog of genre obscurities — creating that suspended moment when one leaves the cineplex but hasn’t yet shifted back to one’s street life.

Ten Enduring Statements from Lost or Forgotten Films

- It was like our souls got sucked through a straw and what was waiting on the other side was a preliminary sketch of the future.

- It is not every day that you can pick out your poison and be happy with the results.

- Listen, will you — it’s doesn’t matter if you’ve never seen anything like this before: No one is going to believe you anyway.

- I’ve seen your face someplace before, and I don’t like where I seen it.

- Just look around — we got photos of every catastrophe imaginable and that’s not all.

- The law requires them to keep you alive until they are sure you are dead.

- Death isn’t a brick wall but a racing bike with a bent back rim.

- I start getting concerned when I feel the cool mud rise between my ears.

- When happens when you learn that your first language has been put on a ventilator?

- You are destined to make the headlines; you just don’t want to read them.

Towards the end of the collection, there is a memorable elegy, “Overnight,” for Paul Violi, opening with Yau’s signature toneless humor: “I did not realize that you were fading from sight / I don’t believe I could have helped with the transition.” There is a poem titled “Angry Birds” which ends, “Small birds fly from my mouth en route to you / Poems enmeshed in sounds I cannot enunciate / These sounds flying from my mouth / covered in spit / my life’s blood.” This foolishness is serious stuff. The exceptional is ordinary in Yau’s work, and vice versa. The final sentences of “Standard Operating Procedure” inform us in an idiosyncratic officialese how we might take all of this:

Towards the end of the collection, there is a memorable elegy, “Overnight,” for Paul Violi, opening with Yau’s signature toneless humor: “I did not realize that you were fading from sight / I don’t believe I could have helped with the transition.” There is a poem titled “Angry Birds” which ends, “Small birds fly from my mouth en route to you / Poems enmeshed in sounds I cannot enunciate / These sounds flying from my mouth / covered in spit / my life’s blood.” This foolishness is serious stuff. The exceptional is ordinary in Yau’s work, and vice versa. The final sentences of “Standard Operating Procedure” inform us in an idiosyncratic officialese how we might take all of this:

“You can decipher these actions by any code that you think fits. I am not one to decide how things should be read. But let me assure that there is far more to be done, even if I am not the one to do them. This is what is meant by the unavoidable reduction to essentials.”

[Published by Letter Machine Editions on April 1, 2018. 135 pages, $14.00 paperback]

References:

César Aira, On Contemporary Art, translated by Katherine Silver: David Zwirner Books, 2018.

Jarrett Earnest, What It Means to Write About Art: David Zwirner Books, 2018.

John Yau, The Passionate Spectator: Essays on Art and Poetry: University of Michigan Press, 2006.