In the age of the selfie, it is difficult at times to conceive of the modern self as something that could exceed the chunky subtext of a meme or algorithmic transcription. Equally difficult is imagining the selfie — even though it is a legitimate form of photographic self-portraiture — as a means of getting any closer to whomever, or whatever, the self actually is, when the selfie is the output of platforms that encourage their users to self-promote, reward self-appeal, and perhaps foster self-delusion. When I open the selfie camera on my Instagram account, a text-bubble pops up to suggest I try on a filter that seeds my cheeks with late-summer freckles, suffusing my face with afternoon light; and in my newsfeed, I, like most, follow (or are recommended to follow) a host of preternaturally good-looking influencers who, by sharing curated images of their aestheticized everyday lives (and turning a profit), inspire followers to do the same. Following in suit, we generate social-currency through self-portraiture of our own.

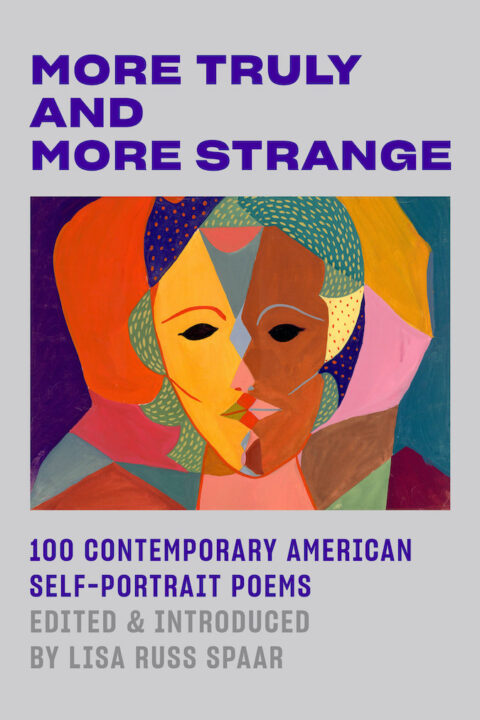

The ubiquity of the selfie, and the culture that surrounds it, make a strong case that generations inured by the image-cultures of the internet may be hopelessly out-of-touch with themselves. A disparity will always lie between who we are and who we present ourselves to be; and while our screens may have enlarged that distance more than ever, there will always be those artists and authors who endeavor to see the way that we would see in a mirror. In her new anthology of 100 self-portrait poems, More Truly and More Strange, Lisa Russ Spaar delivers a deeply informed and refreshing look at what it means to approach the American self in an era when image is dropped from the equation and replaced by lyric word.

The ubiquity of the selfie, and the culture that surrounds it, make a strong case that generations inured by the image-cultures of the internet may be hopelessly out-of-touch with themselves. A disparity will always lie between who we are and who we present ourselves to be; and while our screens may have enlarged that distance more than ever, there will always be those artists and authors who endeavor to see the way that we would see in a mirror. In her new anthology of 100 self-portrait poems, More Truly and More Strange, Lisa Russ Spaar delivers a deeply informed and refreshing look at what it means to approach the American self in an era when image is dropped from the equation and replaced by lyric word.

Few guides are more qualified to lead readers through the niche but robust world of poetic self-portraiture. A professor of English and creative writing at the University of Virginia, Spaar began to teach a course on poetic and visual self-portraiture in 2014. She has since continued to teach, research, and write on the evolution of self-portrayal in visual and written forms, and her articles on the subject have been published in several journals. A poet and critic, she is the author of more than a dozen books, three of which are anthologies.

Entering More Truly and More Strange through her lucid introduction is one of the delights of the book. Witty, clear-eyed, Spaar contextualizes the American self-portrait poem against atavistic backdrops, as she spans the ancient human question of the self, Louise Glück’s influential book American Originality, the American personality since this country’s founding, the poetic innovations of Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman, and the publication of John Ashbery’s catalyzing Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror.

This anthology, however, is not intended as a comprehensive survey, nor is it presented as the best of poetic self-portraiture. A definition for the literary genre is provided — the two factors that qualify a poem as a self-portrait poem, in Spaar’s definition, are that it chiefly concerns itself with matters of the self, and is deliberately self-conscious and/or ‘meta’ about it. She calls it something of a “self-conscious literary entity.” All born between 1926 and 1990, and all born and/or raised in the United States, the poets are both emerging and established, the canonized as well as influential young poets writing today. Among them are Tracy K. Smith, W.S. Merwin, Safia Elhillo, Terrance Hayes, Tarfia Faizullah, Natalie Diaz, Brian Teare, Kiki Petrosino, and Sylvia Plath.

Representing varied and diverse poets hybridized into a single book and a relatively short one at that, these poems show how American selfhood today is defined by collective efforts to revise it, as the voices of those persecuted and excluded in the name of the nation’s founding now bore through its age-old myths of itself. The result, like our current moment, is irreverent, valiant, and fractured. Safia Elhillo, a Sudanese-American poet, rescinds allegiance to land in “Self Portrait With No Flag,” while Hayan Charara’s “You” perceives the self as racially profiled, spoken from the perspective of an airport security officer. The speaker in Tarfia Faizullah’s poem wryly salvages themself from racial stereotype in “Self-Portrait as a Mango”:

She says, Your English is great! How long have you been in our country?

I say, suck on a mango, bitch, since that’s all you think I eat anyway …

… [I know] I’m worth waiting for, I want to be kneaded for ripeness. Mango:

my own sunset skinned heart waiting to be held and peeled, mango

I suck open with teeth. Tappai! This is the only way to eat a mango.

Working in a genre that lends itself to the visual and the paradoxical, almost all of these poems involve some interplay between the “I” and the “Eye,” be that through visual tropes such as photographs, mirrors, and cameras, or sleights of hand that call into question the separateness between the poet and the speaker, and the speaker and their reflection. W.S. Merwin talks to his reflection in “To the Face in the Mirror”: “so how far / away are you / after all who seem to be / so near and eternally / out of reach,” he asks, “you with no weight or name / no will of your own / and the sight of me / shining in your eye,” whereas Brittany Perham’s poem “Double Portrait” does so lyrically, capturing through rhyme and formal play the paradoxical relationship between first- and second-person:

When will you stop being You

who fits inside my catchall Thou

the one I post each letter to?

… a pronoun never loved or grew.

I return you to your common noun;

then you will stop being you.

Who fits inside my catchall thou?

Some of the poems conclude in ecstatic, self-actualizing breakthroughs — self-love trumps rejection, for example, in the Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s “At Last the New Arriving,” as she concludes, “what a prize you are. / What a lucky sack of stars.” The speaker in Anna V.Q. Ross’ “Self-Portrait at Treeline” arrives at “the breaking news of myself,” as does the speaker in R.T. Smith’s “Keel Bone”: “I felt a lifting. I swear this is not lying. It is not nonsense. I might yet soar.” No single poem here manages to construct an all-encapsulating, singular self-portrait, or even tries to — rather they offer us one layer of a Russian doll, holding still a single version of the self as it continues to become without ever really becoming. In Miller Oberman’s words, from his poem “On Trans,” “the process of through is ongoing.”

Self-destruction, self-evisceration, and self-eviction are just as evident, spanning from poems that manage ecstatic escapes from the self via the act of self-portraiture, to others which capture the violence done to the self with unflinching frankness. Self-portraiture as self-resuscitation takes place in Justin Boening’s “Self Portrait in Which I Resemble the Man Next to Me”: “To save myself, I remove myself. / My voice is waking me. / I want it to wake me again.” In “Post-Op Overdose,” Susannah Nevison writes, “It is possible to love what lays me to waste,” yet that very line is challenged by the speaker in Nick Flynn’s “Self Exam: My Body as a Cage,” saying, “we think / we can think anything & it won’t / matter, we think we can think cut out her tongue, / then ask her to sing.”

These poems, moreover, aren’t easy, and it is in the going-through of More Truly and More Strange that we fully comprehend the catharsis that self-portraiture may enact. This catharsis is, in part, personal; for Sylvia Plath, in the poem “Mirror,” taking her bedroom mirror as a narrative mask offers a means of facing age with unflinching frankness:

A woman bends over me,

Searching my reaches for what she really is.

… each morning it is her face that replaces the darkness.

In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman

Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.

… as does Mary Jo Bang: “My eye repeats horizontally what I by / this time already know: there is no turning back to be / someone I might have been. Now there will only ever / be multiples of me.” Among dying, sex, love, illness, rejection, acceptance, the birth of a child, and the death of a loved one, aging is one of those themes that repeats across this collection; those experiences which, for one reason for another, demand or even inflict self-witness, perhaps say more about the common human experience than self-portraiture itself.

“Everyone and everything we see is a self-portrait,” writes Terrance Hayes in the opening line of “Self-Portrait as the Mind of a Camera.” If that’s true, many of us will emerge from this anthology with a strong impression of those portraits that most closely resemble ourselves. There is something for everyone here; crises both timely and timeless merge in this gallery of American identity.

It is within the rigid limits that Spaar imposed on her selection process that these poems crystallize into a hyper-present capture of American selfhood as we see it today. If such is the scope of this project, Spaar is more suggestive than conclusive. In her introduction, she proposes:

“Can a gathering of aesthetically and demographically diverse contemporary American self-portrait poetry — poetry written in the dramatically fraught decades between the mid-twentieth and early twenty-first century, years that have seen technological, cultural, racial, sexual, and political changes of revolutionary import — help us to better understand ourselves and each other: as Americans, as human beings?”

“Can a gathering of aesthetically and demographically diverse contemporary American self-portrait poetry — poetry written in the dramatically fraught decades between the mid-twentieth and early twenty-first century, years that have seen technological, cultural, racial, sexual, and political changes of revolutionary import — help us to better understand ourselves and each other: as Americans, as human beings?”

[left: Lisa Russ Spaar] It would be unreasonable to expect from this anthology a cohesive or definitive understanding of what a self-portrait poem is. Safeguarding her creative agency as an anthologist, Spaar caps this book at 100 poems, imposing a specific time frame that allows her to enlarge this historical moment via the self-portrait poem rather than focusing on the self-portrait poem itself. What readers will gain, though, is a keen sense for the tropes and preoccupations found in a self-portrait poem, the playfulness and mercilessness that tend to characterize them, the urgency with which they disclose of their selves more truly, if more strange.

American poetry has seen a surge in self-portraiture over the last century, ever since the debut of Ashbery’s “Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror” in 1975 — the point at which, Louise Glück points out in “American Originality,” the poet looking inward has begun, simultaneously, to watch themselves looking inward. “Why?” Asks Spaar. She continues:

“An exploration of the reasons is, in many ways, a key to the vision, development, praxis and significance of contemporary American lyric poetry in the context of a nation that is on one hand claustrally cyber-connected and on the other increasingly diverse and ideologically splintered.”

At this moment — fractured, imperiled, and charged — the trend of self-portraiture in American poetry resounds as an echo of the collective effort to cope. With being alive, but also with the Us that America is, wanted or not. Or the Us that is We. Or the Us that is You and Yourself.

[Published by Persea Books on September 8, 2020, 256 pages, $20.00 paperback]