Grace Schulman was known to me as the Director of the Poetry Center of the 92nd Street Y long before I actually met her. For the twenty-something poet I was at the time, the annual membership card that allowed free entry to the Center’s offerings was, by any stretch, a vocational bargain. It’s impossible to exaggerate the effect of my attending these near-weekly readings and talks, the voices and physical presences encountered there having made such lasting impressions. The Y’s Kaufmann Hall, ringed at its ceiling by golden names, was a locus of aspiration and poetic actuality. The person most often at its threshold — that is, standing at the stage’s podium — was Grace. Her distinctive way of speaking became so familiar as to sound familial as she graciously introduced each evening’s set of poets and writers.

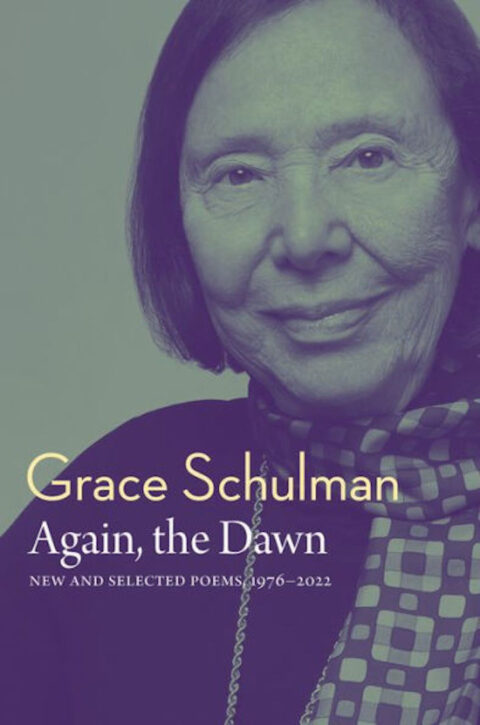

This is the same soft-spoken yet assured voice to be found in Again, the Dawn, Schulman’s latest collection. A gathering of nearly 50 years of New and Selected Poems, it is dedicated to Richard Howard. Richard would become, along with Grace, one of my teachers back in my New York City days. Under the circumstances, there is no way for me to be critically “objective” about such a book. The approach to be taken — which echoes Grace’s own toward her workshop students — is careful observation and focused praise. Come to think of it, and this is obviously no coincidence, such an attitude pervades Schulman’s poetry. It is an approach that finds expression even in her earliest work, as in the passionately elegant “Blessed is the Light” from Hemispheres (1984):

Blessed is the light that turns to fire, and blessed the flames

fire makes of what it burns.

Blessed the inexhaustible sun, for it feeds the moon that shines

but does not burn.

Praised be hot vapors in earth’s crust, for they force up

mountains that explode as molten rock and cool, like love

remembered.

Again, the Dawn is an especially well-edited selection, with a lifework’s currents and concerns returning as quasi-musical themes. Unlike many Selected Poems, their grouped appearance does not feel the least bit premature. (A number of selections, in fact, were previously reprinted in her 2002 Days of Wonder.) And yet without the newest lyrics set at the book’s front, the collection would lack its sense of sure resolution — of imperfect treasures found and put back into place — allowed by the most recent work. In her 2007 “The Broken String,” Schulman recalls a concerto performance in which one of the strings of Itzhak Perlman’s violin snapped. Unable to get up and find himself a replacement, he somehow played magnificently without it, explaining afterwards, “it’s what you do.” As in music, so in poetry you “make new music / with what you have, then with what you have left.” There is for me a particular wonder at the seemingly improvisational way disparate threads — “a teardrop / of a crystal chandelier, // a twist of braided rope / from a sunken ship, the gold locket you lost” — find their perfect weaving in the book’s opening “Invitation”: “Come with me while I drift / then rise to read the waves, // note their force and speed, and ride the breakers in.”

Again, the Dawn is an especially well-edited selection, with a lifework’s currents and concerns returning as quasi-musical themes. Unlike many Selected Poems, their grouped appearance does not feel the least bit premature. (A number of selections, in fact, were previously reprinted in her 2002 Days of Wonder.) And yet without the newest lyrics set at the book’s front, the collection would lack its sense of sure resolution — of imperfect treasures found and put back into place — allowed by the most recent work. In her 2007 “The Broken String,” Schulman recalls a concerto performance in which one of the strings of Itzhak Perlman’s violin snapped. Unable to get up and find himself a replacement, he somehow played magnificently without it, explaining afterwards, “it’s what you do.” As in music, so in poetry you “make new music / with what you have, then with what you have left.” There is for me a particular wonder at the seemingly improvisational way disparate threads — “a teardrop / of a crystal chandelier, // a twist of braided rope / from a sunken ship, the gold locket you lost” — find their perfect weaving in the book’s opening “Invitation”: “Come with me while I drift / then rise to read the waves, // note their force and speed, and ride the breakers in.”

In the early poems of Burn Down the Icons and Hemispheres, Schulman’s vocation of visual and auditory notation first begins to present itself. “Art does not ask fidelity to life,” Schulman will later write, “but ardent precision,” a form of observation derived from Marianne Moore. “In a Country of Urgency, There is a Language,” in fact, is dedicated to the surface-cool Moore, whom the young Schulman knew. But there is also in these first books a sense of heated necessities and burning determinations, the way pagan impulses can’t help but express themselves in the stone of Christian cathedral sculpture. There is in Schulman a sense of response in extremis, “Blood forces up my praise.” For this, one would have to compare the young poet to Moore’s fellow student at Bryn Mawr, H.D. From the seminal “Blessed is the Light,” for example, there are these lines that so powerfully recall H.D.’s imagist possession:

Branches of pine, holding votive candles,

they command, disturbed by wind, the fire that sings in me.

Unfurled over the course of the volume are poems of cosmopolitan travel to Europe, as well as the divided emotions evoked by visits to Israel. But even in these there is a distinct sense that the poet is visiting from New York City, from “New Netherland.” Manhattan in particular is so much a part of Schulman’s emotional context that the city nearly figures as a relative, this urban personage’s seasonal moods expressed as uptown and down. In the downtown synagogue of “Charles Street Psalm,” where “towers redden after sunrise,” twelve “early risers” chant the morning’s praise and recall the dark past of Schulman’s father. The Twin Towers’s falling is also remembered through the “orange alert” of “From the New World.” Yet at the heart of Schulman’s poems is Washington Square, once a potter’s field, echoing ghostly voices heard in her work as allusion and prosodic echoing: “We pass The Row, each day.” Greenwich Village, among other things, serves as a locus for serious jazz. where “snapped fingers … / shape pain into order. That was form.” From the Village’s “dope fumes, / dog piss, rat poison, banal conversations,” a subway ride (alongside W.H. Auden on the No. 6) takes readers uptown to the meaningful “Elegy Written in the Conservatory Garden” where “cocoa mulch merges with hints of urine” and “blossoms mix with candy wrappers.”

Schulman’s strong ekphrastic impulse provides a kind of recurring refrain for the collection, especially in description of religious painting, where “the light pours down / less on the holy figures than on objects / waiting to be used,” such as “the persimmon in St. Anne’s hand / as she teaches the Virgin to read.” This is less a matter of religious topics than religious impulses. There is the determined impiety of “Chaim Soutine” and his own pained and forbidden “graven images,” as well as of the Parisian art critic who repeats the assertion that “the palette is the devil’s platter.” The productions of the Creator himself are subject to Schulman’s consideration, culminating in the monotheistic punchline of “God Speaks”: “I always work alone.” From “Confessions of a Nun” back to “Written on a Road Map,” religious myth makes its presence known through human figure and natural image:

Barbara of the storm, John of the sea,

Saint Catherine fix me here, your fire my fire,

Establishing a chapel on a map

To stop the blur of trees, the flow of roads.

Lines from “The Abbess of Whitby,” one of the book’s earliest poems, both heralds and describes the nature of the poet’s vocation:

Holy men wondered that so great a power

Could whirl in darkness and force up his song;

There must have been an angel at his ear

When Caedmon gathered up his praise and sang.

For listening and observation are Schulman’s foundational approaches in her own psalms’ creation. She writes about a powerful experience when as a child she was taken by her father to see King Lear and came to know that “watching was a kind of prayer.” Or as she writes at the close of “Ascension,” “I’ll be there, / gazing impiously — unless / that is what sacred is, the work, the looking up, / the wonder.”

Recent work also recalls Schulman’s marriage, whose echoes reach back to “Psalm for an Anniversary” from her 2001 The Paintings of Our Lives: “Praise to the sun / that flares and flares again in fierce explosions / even after sunset.” Set forth in work from The Marble Bed (2020) are the specificities of love and grief, a personal narrative also related in her prose memoir, Strange Paradise. Long Island Sound is the choral backdrop for this absence containing presence, the poet’s craft a sailboat on “Judah Halevi’s sea” negotiating choppy experience. The “rasping’” sea itself “writes and revises, / breaks, pours out, recoils,” with the surge turning as a form of enjambment: “Breakers roared when Caedmon sang Creation / in a new verse with the rhythmic pull of oars.” Towards the front of the collection, there is a distinct paring down of effects and increased clarity of line that at moments approach the Merwinesque: “Angry winds, / as the moon eclipsed is still the moon / dark in a sharp circle. “ It was through his friendship with Grace that I met W.S. Merwin, so I may be forgiven for hearing him in vocative lines like “Follow the phosphorescent line / marking the road’s edge, even on dark nights, / and watch it flow until you smell the sea” or “Observe the ocean / that draws back only to move ahead.”

Recent work also recalls Schulman’s marriage, whose echoes reach back to “Psalm for an Anniversary” from her 2001 The Paintings of Our Lives: “Praise to the sun / that flares and flares again in fierce explosions / even after sunset.” Set forth in work from The Marble Bed (2020) are the specificities of love and grief, a personal narrative also related in her prose memoir, Strange Paradise. Long Island Sound is the choral backdrop for this absence containing presence, the poet’s craft a sailboat on “Judah Halevi’s sea” negotiating choppy experience. The “rasping’” sea itself “writes and revises, / breaks, pours out, recoils,” with the surge turning as a form of enjambment: “Breakers roared when Caedmon sang Creation / in a new verse with the rhythmic pull of oars.” Towards the front of the collection, there is a distinct paring down of effects and increased clarity of line that at moments approach the Merwinesque: “Angry winds, / as the moon eclipsed is still the moon / dark in a sharp circle. “ It was through his friendship with Grace that I met W.S. Merwin, so I may be forgiven for hearing him in vocative lines like “Follow the phosphorescent line / marking the road’s edge, even on dark nights, / and watch it flow until you smell the sea” or “Observe the ocean / that draws back only to move ahead.”

Refuge from Covid provides the ostensible subject for Schulman’s prayer-like “Scallop Shell.” An important visual motif throughout her poems, here shells spark a meditation on shape and pattern. The poem’s repeated alternation from paired triplets to couplet winds down to its closure from three lines, to two, to the single-lined envoi:

See them at low tide,

scallop shells glittering on

a scallop-edged shore,

whittled by water

into curvy rows the shape

of waves that kiss the sand

only to erode it. Today

I walked that shoreline, humming,

Camino Santiago,

the road to St. James’s tomb,

where pilgrims traveled,

scallop badges on their capes,

and chanted prayers

for a miracle to cure

disease. And so I,

stirred by their purpose,

hunted for scallop shells

shaped like pleated fans,

with mouths that open and close

to steer them from predators.

I scooped up a fan

and blew off sand grains, thinking,

for that one moment,

of how Saint James’s body

rose from sea decked with scallops,

and of this empty beach

in another austere time.

Let this unholy pilgrim

implore the scallop shell,

silvery half-moon, save us.

Such recognitions of the holy in art and nature form a kind of ars poetica producing undulating lines in which one can hear the swing of the tide. “I, / whose heirs are words, wish for them: fly / … long over water and survive.” The prosody is one of gentle yet purposeful movement; like scallops themselves, the speaking mouth becomes both a mode of survival and of psychic locomotion.

Again, the Dawn’s assembled contents also bring forth a sense of “movement” in its other usage, when the word refers to the related sections into which musical compositions are divided. Each movement takes place in varied tonal or rhythmic locations, but when performed together in sequence, the themes of its oceanic voyage come together to create the arc of an emotional and intellectual journey. At the music’s close there arrives a feeling of resolution, thrills of balloon-light technique balanced by soulful ballast. This, for me, is exactly the after-feeling created by Again, the Dawn. At the conclusion of a stirring performance, after the catharsis of applause has fallen to silence, there follows the thoughtful exit from an auditorium or nightclub made hallowed by art. For the poems of Grace Schulman, as well as for the work of such poetic practitioners I’m fortunate to have known, I myself can only declare, “Praised be.”

[Published by Turtle Point Press on November 15, 2022, 256 pages, $22.00 paperback]