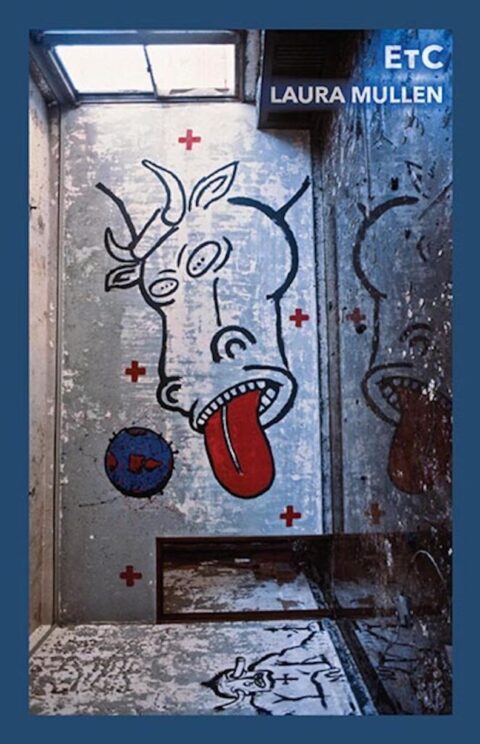

During the years of my soccer motherhood, when my daughter was younger and played for a club called Eastside on Oahu, her team practiced on a field where an old dairy had operated. The grass was luscious, the view of the mountains sublime. Each week the coach would send out an email to announce that practices would be held at “Souza Diary.” As an English professor, I got a chuckle out of the pun (unintended) between a place where cows are milked and a space in which girls (stereotypically) write down their memories. I didn’t go any further with the pun. But Laura Mullen has — her new book, EtC, grows from the pun on industrial farming and institutional higher education. The “diary,” you see, is lodged in a “Department of Anguish,” a place where many get milked.

The British-Australian writer and scholar Sara Ahmed has done important work on bullying and harassment in higher education, the ways that institutions, in claiming to mitigate lacks of diversity and other ills, create structures that merely perpetuate the status quo. One of her interlocutors formed a reading group in her department that was quickly dominated by senior male professors; judgments were cast, and racist jokes were told. Laughter ensued, as it does. In What’s The Use, Ahmed notes that “These were the sorts of things: sentences as sentences; violence thrown out as how some are thrown out. Even the air can be occupied.” Puns can enact the Catch-22s of academe, if not quite explode them. When the woman lodged a “complaint,” based on the testimonies of 20 people in her department, she wasn’t ignored (one strategy used by administrators); instead, she was accused of “arrogance” and “self-promotion.” And then the complaint was ignored.

The British-Australian writer and scholar Sara Ahmed has done important work on bullying and harassment in higher education, the ways that institutions, in claiming to mitigate lacks of diversity and other ills, create structures that merely perpetuate the status quo. One of her interlocutors formed a reading group in her department that was quickly dominated by senior male professors; judgments were cast, and racist jokes were told. Laughter ensued, as it does. In What’s The Use, Ahmed notes that “These were the sorts of things: sentences as sentences; violence thrown out as how some are thrown out. Even the air can be occupied.” Puns can enact the Catch-22s of academe, if not quite explode them. When the woman lodged a “complaint,” based on the testimonies of 20 people in her department, she wasn’t ignored (one strategy used by administrators); instead, she was accused of “arrogance” and “self-promotion.” And then the complaint was ignored.

Ahmed also quotes a student who came back to a department after some time away. She felt disconnected from what appeared to be a place of harassment, both physical and psychic (jokes again). The woman reports, “They were talking about ‘milking bitches.’ I still can’t quite get to the bottom of where the jokes were coming from.” But everyone was laughing. And then the transposition to fishing and catching, or versifying, as Ahmed writes, “Each time the expression is used, that history is thrown out like a line, a line you have to follow if you are to get anywhere.” The phrase “milking bitches” is the line. A line is also administrative jargon for a job.

I can’t figure out whether to call EtC double-realism or double-allegory, but it does the work of both by way of satire. Her Elsie is a very decorated cow/professor, possessed of “Degrees, including ‘Doctor / of Bovinity, Human Kindness, / And Economics.” Professor Cow, as I shall call her, “Grows up marries / Chairs a Department / Of Anguish 3 years / In the Diary Industry.” But like any industry manager, this department Chair needs to trim the sails to accommodate “reductions in market / Share,” so she calls a meeting. Anyone who has worked in an English department knows that the first budget item cut is “copying.” We all milked those machines with hand-outs for our students and with copies of our own work. So “stop all this copying now,” she ordains. In my department, printers were next on the chopping block, bringing production into line with re-production. Oh, and there was no more paper, either.

“Copying” is a loaded word, of course. You can reduce your budget by turning off the Xerox machines, but there’s human copying to worry about, too. Yes, there are copyright laws to protect us from having our work milked by others, or our image marketed by someone else. We are talking “promotion” here, both of one’s work and in one’s job. Tenure ends the need for promotions, but by then you’re well taught in the craft. The law of “citation” isn’t far behind the “originality requirement.” (That Mullen’s Bibliography is called “Supply Chain” nails down the link between Diary and Dairy.) You need to act like an original, while occupying the space of a copy. That is a crucial matter for Elsie, who inhabits dairies and a poem by William Carlos Williams; Mullen asks us to wonder if Williams’s Elsie is not a cow, or vice versa. Williams seems to talk of her as one, with “her great / ungainly hips and flopping breasts.”

“Copying” is a loaded word, of course. You can reduce your budget by turning off the Xerox machines, but there’s human copying to worry about, too. Yes, there are copyright laws to protect us from having our work milked by others, or our image marketed by someone else. We are talking “promotion” here, both of one’s work and in one’s job. Tenure ends the need for promotions, but by then you’re well taught in the craft. The law of “citation” isn’t far behind the “originality requirement.” (That Mullen’s Bibliography is called “Supply Chain” nails down the link between Diary and Dairy.) You need to act like an original, while occupying the space of a copy. That is a crucial matter for Elsie, who inhabits dairies and a poem by William Carlos Williams; Mullen asks us to wonder if Williams’s Elsie is not a cow, or vice versa. Williams seems to talk of her as one, with “her great / ungainly hips and flopping breasts.”

AT THE BORDER COMPANY

In the diary barn

Everyone is writing

And no one can really

Talk What are you working on

Is the only question

I’m working on a book

About a cow who goes

To space And you O great

Count every word

Adding white to white

So where does she go

The cow The Milky Way

Of course and never

She never comes back

Sometimes someone else writes lines that we identify with so much we want to use them for ourselves. This is the case with Laura Mullen who wanted to quote Tom Petty’s 1980 song, “Refugee,” in her book. But it would have cost too much, as a lawsuit over appropriating the image of, say, a cow, might do. This part of Mullen’s book struck me closely. We were both born in 1958, as was Mullen’s dear friend, the late Marthe Reed, to whom the book is dedicated. Perhaps because my middle name is Martha, I remembered Marthe’s story of how she got her name. Her father loved cows, so he named one Martha. Then, the better not to confuse them, I guess, he named his daughter Marthe. “Chain chain chain,” Aretha Franklin sang “Chain of Fools,” but Little Richard wrote it. (I did not know that.)

Like me at a certain age (that sometimes includes now), Mullen describes belting out Tom Petty’s lyrics “Along loudly I was full of self- / Pity thought the words I couldn’t / Afford or get permission to use / Were meant for me …” Here “self” enjambs before “Pity,” as if Mullen herself could be Petty, but can’t be because regulations stand in the way. “End of the line,” sang the Traveling Wilburys, who included Petty. The question of how to define a “refugee” is one that Petty neglects in his song. She concludes, “Because we’re trying so hard / To remember the words / And forget the meaning.” A pop song can stand in for our feelings, but only if we believe the singer sings to us alone. Petty probably didn’t feel like a refugee for the same reasons Mullen does (though there is the music business, after all). But his words cover a multitude of exiles, including (?) the non-metaphorical ones.

To feel what the culture tells you to feel is to appropriate something. The top appropriators in Mullen’s book are the Beatles, who took Black music and made it white English for the consumption of white Americans. (I might have chosen the Stones for their more blues-saturated rock ‘n roll.) The appropriating mop tops were so alluring that girls screamed and left the smell of their piss behind at Beatles’ concerts. The Beatles played the Cow Palace, which leads Mullen to Gertrude Stein in the next poem. Stein wrote that Alice “had a cow.” Could “to have a cow” denote orgasm, as many feminist critics have argued? Or did it mean that Alice suffered from constipation? Mullen holds to the second interpretation, noting that “A cow is a cow is a cow, and poetry (a code written more often for lovers than soldiers) is what needs to come out.” By now in the book, the Beatles have somehow become our mothers. John Lennon primally screamed for his lost mother, replaced by Yoko; Gertrude called for Alice, and Mullen for the cow as a cow as a cow. These are copies with a difference. Insistence rather than repetition. No copyright needed.

Dairies brand their cows, advertising agencies brand companies, academics brand themselves. The self-brand easily becomes a narcissistic wound, opened wide on twitter, Facebook, Instagram and many social media sites between. The academic brand may masquerade as “thinking,” but it proves to be more material than that. In a dream about cows, the poet writes of calves being flayed: “they / Spoke only between cries / Of pain of their brand / How to use their youth and / Beauty to sell their books.” Cows metamorphose into women academics in this dream, as elsewhere in Mullen’s book. “Love in English Lit” is not a soap opera, but alludes to reality operas in which young women married (past tense not completely) their professors and were hired because the institution “had to have a woman.” They often transmogrified into adjuncts, a lesser paid, more precarious, kind of cow. At the end of two single-spaced pages of academic groping and abusing, Mullen’s prose piece comes to a crashing halt with the departmental assertion of the idealism that originally seduced us into the field. “You will want to remember that we value the imagination and have the highest esteem for the infinite capacities of the human heart.” The sizzle of that sentence (about that sentence, as Ahmed might remark) merits the best of emojis. That’s the way we brand our emotions, you see, but you can at least choose the one that vomits green from its little emoji mouth, speaking for you, so to speak.

Dairies brand their cows, advertising agencies brand companies, academics brand themselves. The self-brand easily becomes a narcissistic wound, opened wide on twitter, Facebook, Instagram and many social media sites between. The academic brand may masquerade as “thinking,” but it proves to be more material than that. In a dream about cows, the poet writes of calves being flayed: “they / Spoke only between cries / Of pain of their brand / How to use their youth and / Beauty to sell their books.” Cows metamorphose into women academics in this dream, as elsewhere in Mullen’s book. “Love in English Lit” is not a soap opera, but alludes to reality operas in which young women married (past tense not completely) their professors and were hired because the institution “had to have a woman.” They often transmogrified into adjuncts, a lesser paid, more precarious, kind of cow. At the end of two single-spaced pages of academic groping and abusing, Mullen’s prose piece comes to a crashing halt with the departmental assertion of the idealism that originally seduced us into the field. “You will want to remember that we value the imagination and have the highest esteem for the infinite capacities of the human heart.” The sizzle of that sentence (about that sentence, as Ahmed might remark) merits the best of emojis. That’s the way we brand our emotions, you see, but you can at least choose the one that vomits green from its little emoji mouth, speaking for you, so to speak.

Late in my career, I started an email group for women friends in the academy who were being bullied. There were not many of us in the group, though we knew that many more worked outside our virtual net. What small comfort we took was that our stories were similar. Where we had felt the pain of originality, we now felt the easing of our copyright, held in the company of those considered strange in their departments but that matched our faces in the mirror. That doesn’t completely mitigate individual hurt within an inhumane institution. There’s a lot of pain in (and out of) this book. Mullen has written about her experience of workplace violence at one institution; since the book was finished, she has had to retire from another university over a tweet she wrote about Gaza after October 7, a tweet that agitated some students’ parents and inspired death threats against her. But the triumph of Laura Mullen’s book is that she has written and foretold this history with savage humor. The laughter of the Medusa resounds. The book should be required reading for new (or attempted) academics, as for those of us who love to be astonished by poetry.

[Published by Solid Objects on November 2, 2023, 104 pages, $18.00 US paperback]

Notes

Sara Ahmed, What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use. Duke University Press, 2019. Thank you to Mike Kalish for confirming the story about Marthe Reed’s first name.