on Random Access, photographs by John T. Hill

In 1996, while managing global communications for a technology corporation, I assigned myself the task of writing a feature on how Iveco, the truck-making division of Fiat, was using my company’s systems. Iveco is located in Turin, Italy, the home of Cesare Pavese (1908-50), one of my essential poets. My travels were often motivated by personal interests. Such work assignments included the taking of photos – of the customer, their products and environs. A graphic designer suggested that I hire John Hill. I was told that John had been teaching photography at the Yale School of Art and Architecture since the late 1950’s and had founded the University’s first Department of Photography. He had also taught graphic design.

Meeting up with John in Turin, I discovered someone who had the same cause for visiting Iveco as I did – to make one’s way in the world and take a close look at a city resonant with our respective enthusiasms. I found him to be genial, spry, engaging, and attentive, a most worthy travel companion. And funny. While we were there, the exhibit of the Shroud of Turin was closed – John suggested that perhaps the artifact was out for dry cleaning.

John and I shared the sense that everything in the world is potential material for art. I no longer have any of his Iveco photos but I do have my travel notebook. “He’s as interested in [Iveco’s] production line as he is in the bustle of the Via Roma,” a main street in Turin. My wife Nancy accompanied me on this trip, and when John and I weren’t dealing with the customer he would sometimes head off alone to shoot and we would go in search of Pavese. Over dinner one night, John told us about his experiences as the photographic executor of the Walker Evans estate — his tenure as executor extended for 19 years, and he helped to make it possible for the Metropolitan Museum of Art to acquire the Evans archive. In 2005, he sent us a gift – a digital proof print of Evans’ 1936 portrait of Allie Mae Borroughs. By then I knew a lot more about John’s significant exhibit curatorships and his editing of photo collections. Beyond Evans (he edited six books of Evans’ work), he either curated shows or edited books of Calder, Edward Weston, Peter Sekaer, Erwin Hauer, and W. Eugene Smith.

For several years, I knew very little about John’s own work. We now have Random Access: Photographs by John T. Hill, a selection of 79 images spanning 70 years, 1952 through 2022. The collection’s title is most apt. It’s clear that John had no interest in erecting a monument to himself by forcing patterns or themes on his work where none call out for recognition. Instead, John invites the looker to consider how a single temperament can be reflected through a variety of encounters with reality. In his essay in W. Eugene Smith: Photographs 1934-1975, a book he co-published in 1998, he wrote, “A single obsession underlies Smith’s working process and that was the urge for total control – control of every micro and macro aspect of the production and presentation of his story.” Certainly such careful management has been important to John as well. But when he sent that book to me in 1998, he included a letter in which he says, “Smith was once my ‘main man.’ But along came {Robert] Frank and Evans.” This tells me that he made generous allowances for happenstance and whimsy.

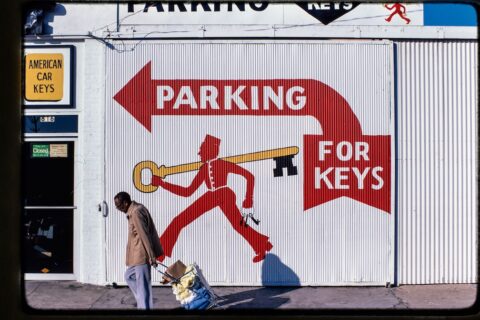

[untitled, California, no date given]

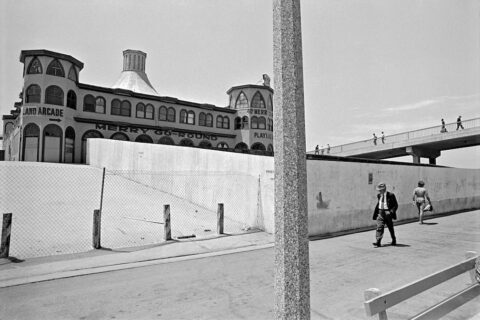

[Santa Monica, California, ca,. 1960]

The arrangement of Random Access proves this last point, since the arrangement itself is whimsical. The work does not proceed chronologically, but one does find two or three images from one period or location grouped together. The oldest photos were taken in Georgia in 1952 — John was born in Jackson County in 1934; he returned over the years to shoot there. From that same year we also find photos taken in a Manhattan automat. In 1958, he was in Brazil. From 1960 come images of a rally for presidential candidate John Kennedy (including a great close-up) as well as images taken in Santa Monica and Malibu. In the 1960s, he took pictures in Rome and at the beach at Anzio. His later photos often look at New Haven and around his home in Bethany, Connecticut.

If you have a copy of Edna Lewis: At the Table with an American Original (or any of her first three books), you’ll see John’s portraits on the covers. His first portraits of her are from “1971 to around 1986.” In an interview in 2018, he notes that Edna and he “picnicked together in Central Park” and went to David Bouley’s restaurant (“we arrived without notice” but Bouley came out to give her a tour of the kitchen).

[Edna Lewis, Duane Park at Hudson Street, New York, 1983]

Street scenes, portraits, images of graffiti and arrays of objects, still lifes – the eye zooms in and out. In his brief introduction to Random Access, John writes, “When I’m holding a camera, I am receptive to whatever I may find most provocative. Baudelaire described this in his account of the flaneur, that person who goes out with an open eye and mind. My goal is to record chance happenings that strike a visual chord. In these photographs, what drives me re two things. One is selecting a worthy subject. The second is to create a visual tension.” John’s training in design reveals itself in two ways. His street photos were created in a fraction of a second, yet they are as gorgeously composed as if he had toiled to get them just right. The shapes found in his urban scenes often resemble and resonate with each other. In other photos, intrigued with color and forms, it seems as if he was absorbed into what he saw and context becomes secondary or irrevelant.

I esteem John’s work and thrived on his fellowship. In addition to his letter of December 1998, John also inscribed the copy of W. Eugene Smith for me. He wrote, “Ron. Remember Mr. Smith’s advice – manipulation is necessary to get to the truth – or something like that.”

[Published by Steidl on April 18, 2023, 154 pages, $40.00 hardcover, 79 color and black & white images]

[Galveston Beach, Texas, 1981]

[Souvenir Shop Facing St. Peter’s Square, Rome, Italy, 1964]

* * * * *

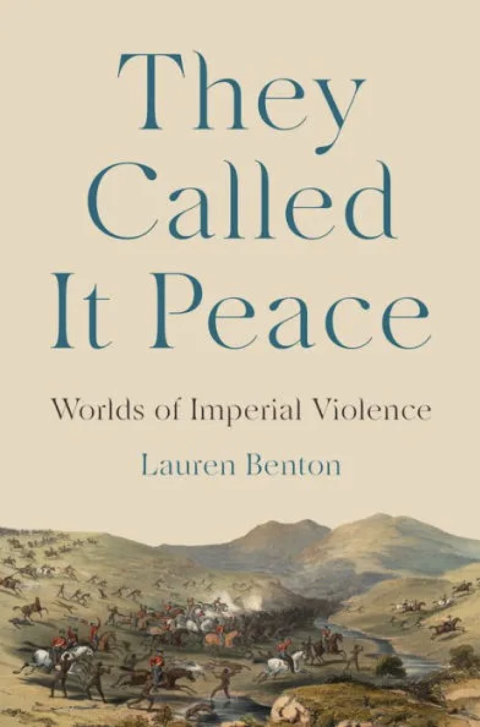

on They Called It Peace: Worlds of Imperial Violence by Lauren Benton

The Seven Years’ War of 1756-63 involved all of the dominant European powers, with France and England as the main antagonists. It was taught to me in high school as the French and Indian War, the American front of hostilities fought on five continents. On May 28, 1754 in what is now Fayette County, Pennsylvania, 44 armed settlers and a small number of Mingo warriors, led by the 21-year old colonel George Washington, ambushed 35 French Canadians and killed their commander. As Lauren Benton relates in They Called It Peace, “The French protested that the English, engaging in an offensive war during peacetime, had murdered the officer … The English complained that he was ‘actually commanding the French Party’ with ‘hostile orders’ still in his pocket.” The great powers were learning how to extend military force over great distances and maneuvering toward a “legal order” to manage their relations and supposedly keep the peace. But Benton’s main point is that “Europeans and Indigenous actors were creating and preserving spaces for violence at the threshold of war and peace.” They were devising new ways of conducting “limited warfare as the centerpiece of regional and global order.”

The Seven Years’ War of 1756-63 involved all of the dominant European powers, with France and England as the main antagonists. It was taught to me in high school as the French and Indian War, the American front of hostilities fought on five continents. On May 28, 1754 in what is now Fayette County, Pennsylvania, 44 armed settlers and a small number of Mingo warriors, led by the 21-year old colonel George Washington, ambushed 35 French Canadians and killed their commander. As Lauren Benton relates in They Called It Peace, “The French protested that the English, engaging in an offensive war during peacetime, had murdered the officer … The English complained that he was ‘actually commanding the French Party’ with ‘hostile orders’ still in his pocket.” The great powers were learning how to extend military force over great distances and maneuvering toward a “legal order” to manage their relations and supposedly keep the peace. But Benton’s main point is that “Europeans and Indigenous actors were creating and preserving spaces for violence at the threshold of war and peace.” They were devising new ways of conducting “limited warfare as the centerpiece of regional and global order.”

Writing about small wars that erupted from the 15th to the 19th centuries, Benton describes the actions of colonial powers that established settlements, plundered local resources, and enslaved people. When local insurgents fought back, colonialists responded with overwhelming force, further tightening their grip. “Over the course of the nineteenth century, the idea of a global regime protecting Western interests pervaded visions of peace based on commercial expansion, democratic alliances, and visions of global dominance by White civilization,” Benton writes. The peace would be enforced.

Benton asserts that “protecting” colonial interests entailed keeping violence-on-tap – and that this model for legitimizing bloodshed remains at work today. She quotes Vladimir Putin who appeared on Russian state television on February 22, 2022 to say of his invasion and bombing of Ukraine, “This purpose of this operation is to protect people who, for eight years now, have been facing humiliation and genocide perpetrated by the Kviv regime,” recalling, says Benton “the logic of protection emergencies across the nineteenth-century world.” Just as Putin refuses the recognize the legitimacy of Ukraine as a state, colonial powers believed that only they had both the right and expertise to wage peace.

Benton is a professor in Yale’s history department, and also a professor of law at Yale Law School. As in two previous books that integrate the history of European empires and the development of international law, in They Called It Peaceshe tracks the efforts of major powers to agree upon rules of engagement between them. Those rules eventually morphed into those ineffectually imposed the World Court. In the past 15 years, Israel has responded to rocket fire by Hamas from Gaza by launching five offensives. In his article on “Israel’s Descent” in London Review of Books (6/20/24), Adam Shatz called those actions “colonial counterinsurgencies,” a term Benton perhaps would employ as well. One would be in error when regarding these aggressions as only “colonial” or “capitalistic” or any other popular epithet. Boundary skirmishes, land grabs, hostage taking and kidnapping had long been tactics of tribal wars, for instance, among indigenous tribes of North America.

Benton is a professor in Yale’s history department, and also a professor of law at Yale Law School. As in two previous books that integrate the history of European empires and the development of international law, in They Called It Peaceshe tracks the efforts of major powers to agree upon rules of engagement between them. Those rules eventually morphed into those ineffectually imposed the World Court. In the past 15 years, Israel has responded to rocket fire by Hamas from Gaza by launching five offensives. In his article on “Israel’s Descent” in London Review of Books (6/20/24), Adam Shatz called those actions “colonial counterinsurgencies,” a term Benton perhaps would employ as well. One would be in error when regarding these aggressions as only “colonial” or “capitalistic” or any other popular epithet. Boundary skirmishes, land grabs, hostage taking and kidnapping had long been tactics of tribal wars, for instance, among indigenous tribes of North America.

The momentum of They Called It Peace is hampered in places by Benton’s reiterations – and for most readers, her narratives of uprisings and crushing retribution will be more appealing than her analyses of so-called legal order. But no one has been more articulate than Benton in showing how “The regime of armed peace mapped clear pathways from lawful interventions with modest objectives to brutal campaigns of dispossession and extermination … a move from treating individuals as criminals to defining whole communities as natural enemies.”

[Published by Princeton University Press on February 13, 2024, 304 pages, $39.95 hardcover]

* * * * *

on The Work of Art: How something comes from nothing by Adam Moss

As the famed but creatively blocked Silesian writer, Gustav von Aschenbach, proceeds to his fateful end, the narrator of Thomas Mann’s Death In Venice says of him and his behavior, “It is most certainly a good thing that world knows only the beautiful opus but not its origins, not the conditions of its creation; for if people knew the sources of the artist’s inspiration, that knowledge would often confuse them, alarm them, and thereby destroy the effects of excellence.” But indicating those sources is exactly what Mann is doing, since he knows that the “excellence” of his own tale not only hinges on our interest in such interior gropings, but also arises from his own disguised urges.

As the famed but creatively blocked Silesian writer, Gustav von Aschenbach, proceeds to his fateful end, the narrator of Thomas Mann’s Death In Venice says of him and his behavior, “It is most certainly a good thing that world knows only the beautiful opus but not its origins, not the conditions of its creation; for if people knew the sources of the artist’s inspiration, that knowledge would often confuse them, alarm them, and thereby destroy the effects of excellence.” But indicating those sources is exactly what Mann is doing, since he knows that the “excellence” of his own tale not only hinges on our interest in such interior gropings, but also arises from his own disguised urges.

There is no paucity of studies, craft workbooks, interviews and artist autobiographies and essays on the nature of creativity. So when such a book stands out, I want to know why it resonates with me. Perhaps one reason that Adam Moss’ The Work of Art stands out is his own motivation. In his introduction, he talks about looking at sketches and says, “What I find most satisfying about them is the way they seem to embody anticipation.” Moss likes to paint but “got frustrated easily and gave up easily, never knowing when to persevere or surrender … as if I had an overeager immune system that was sabotaging me.” And so, he conversed with 43 artists and writers “to try to capture the artist’s process in all is mundanity.”

What he gives us aren’t roadmaps or sets of instructions. The Work of Art is enriched by the artists’ idiosyncrasies, provisional gestures, gatherings of fragments, and the atmospherics of waiting, sometimes for years, for the convincing if unexpected sound, image or form.

Take Gregory Crewdson, whose large and “exquisitely lit staged dreamscapes” that resemble tableau movie stills seem so meticulously produced that waywardness would hardly seem to be involved. But “location scouting” for him is “just me driving around.” He found the site for “Redemption Center” in Pittsfield, MA., brought his partner Juliane to look at it, and described “where the frame begins, where it ends, what might be happening in the picture. And she’ll take notes.” But he supplies no story. “I’m interested in the moment,” he says. “I almost don’t want to know what’s going to happen before or after. I work in motifs mostly. All artists do. All artists create iconography for themselves over a period of time. And that’s kind of unconscious.” He goes on to describe the production with a crew of about 45 people – and the mystery about the planned image that continues even as the details are settled. Throughout The Work of Art, I was struck by how well edited the contents are, how Moss keeps the suspense going. The book’s variable design grid system and typography make each spread unique, enhancing the experience of discovering the emerging patterns of creativity in the narratives.

Gregory Crewdson, “Redemption Center,” 2018-19, 50×89″

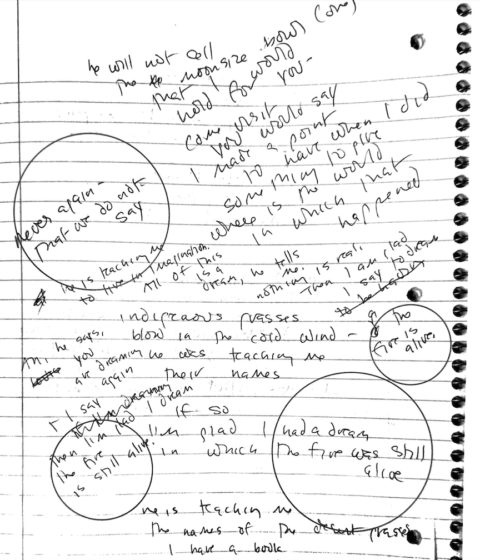

The subject of Louise Glück’s segment is her poem “Song” from Winter Recipes from the Collective. She had started the work by jotting phrases in a notebook and on a slip of paper during a faculty meeting. Moss asked, “Did you start making practical steps toward turning it into a poem?” She replied, “I don’t do it like that.” She says, “At the very beginning, when I have only a fragment of language or even two pieces that seem related, I just, in a sense, ignore them. But the ignoring allows for a kind of haunting.” To elicit more insight from her, Moss quotes lines from her essay “The Education of the Poet” to which she responds with memories of writing, or trying to write, “The Wild Iris.”

Louise Glück’s notes on “Song’

The genesis of Lincoln in the Bardo is George Saunders’ subject here, from his first sighting of the Oak Hill cemetery which Lincoln had visited after the death of his son Willie. A decade went by and Saunders wrote other things. Then seven or eight more years passed. Other stories were written. Saunders’ equable description of progress toward the novel is both charming and daunting – the perseverance seems extraordinary, but something in his nature allows the work to unfold as it seems to want to do.

Some other chapters that especially engaged me focused on Sheila Heti, Suzan-Lori Parks, Sofia Coppola, Ami Silliman, Max Porter and Wesley Morris. Cheryl Pope describes the making of “Mother and Child on a Blue Mat,” a textile painting made after her third miscarriage that expresses “what I wanted to happen, what I imagined would happen, what didn’t happen.” Moss writes, “Of all the decisions she had to make for this work, the hardest might be the decision to give faces to the mother and baby, or not – to make the picture specific or to generalize, to close it, in her words, or to open it.” Pope said, “Listening is at the ground of all of this … In those moments of debate, I just tried to stay very quiet, listening for what she wants me to do.”

Edward Albee once quipped, “The thing that makes a creative person is to be creative and that’s all there is to it” – an apt response to someone intruding into the artist’s space with a question that can’t be answered except at length. But Adam Moss takes us into the memories of having wandered intentionally into that classical zone of unknowingness. Or as Marie Howe told Moss about writing poetry, her best work comes when she is “in my nightgown for days, not thinking about anyone else. It takes a couple of days just thrashing through the brambles to get to any type of clearing, and it’s very painful. It’s frustrating, you see all your limitations, but a lot of what is happening is the unconscious is just waiting to see if you mean it.”

[Published by Penguin Press on April 16, 2024, 424 pages, $45.00US/$60.00CAN hardcover]

* * * * *

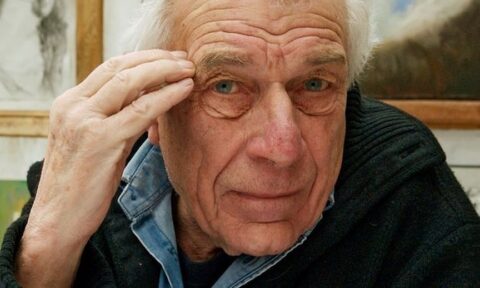

on Cataract: Some notes after having a cataract removed by John Berger, with drawings by Selçuk Demirel

In 2023, almost four million cataract surgeries were performed in the United States, making it one of the most commonly performed procedures. About 90% of patients regain 20/20 vision after the surgery. But there was nothing common about John Berger’s reaction to the removal of cataracts, first on his left eye, which occurred on March 26, 2010 at age 84. By June, he had already published a short essay about his experience in the British Journal of General Practice.

In 2023, almost four million cataract surgeries were performed in the United States, making it one of the most commonly performed procedures. About 90% of patients regain 20/20 vision after the surgery. But there was nothing common about John Berger’s reaction to the removal of cataracts, first on his left eye, which occurred on March 26, 2010 at age 84. By June, he had already published a short essay about his experience in the British Journal of General Practice.

One of Berger’s most lyrical early essays is “Five Ways of Looking at a Tree.” Ways of Seeing is usually named as his most widely read and influential book (and the title of his popular BBC series on art). Looking had significant implications for Berger who died in 2017. In 1959 he wrote, “Every way of looking at the world implies a certain relationship with the world, and every relationship implies action.” As Joshua Sperling put it in his study of Berger, A Writer of Our Time (2018), “A ‘way of looking,’ understood as an attitude, orientation or worldview so intrinsic to the person it coloured perception and became almost a way of being – this was central to Berger as he enlarged his understanding of the political and its intercourse with the aesthetic.”

And more: “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognises before it can speak. But there is also another sense in which seeing comes before words. It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.”

The 2010 essay has now been resurrected as a chapbook, Cataract: Some notes after having a cataract removed, accompanied by the drawings of the Turkish artist Selçuk Demirel. Four days after the procedure, he wrote, “May 30th. Unusually blue sky, by any standards, over Paris. I look up at a fir tree and I have the impression that the little fractal fragments of sky, which I see between the masses of pine needles, are the tree’s blue flowers, the colour of delphiniums.” At this point, the cataract on the right eye hadn’t been removed, so he would compare the effects offered by each eye. He wrote, “With the right eye alone, everything looks worn, with the left eye alone, everything looks new. This is not to say the object being looked at changes its evident age; its own signs of relative age or freshness remain the same. What changes is the light falling on the object and being reflected off it. It is the light that renews or — when diminished — makes old.”

He remarks on depth of vision, the qualities of light, the displays and variations of color. There are also assertions: “Let’s be clear about the implications of what I’m saying. Clearly, during many decades after my childhood, I saw sheets of white paper as white as this one. But gradually the whiteness dimmed without my taking account of it. Consequently, what I called white paper, changed, grew dimmer. And this afternoon what’s happening is not that I realise this with my intelligence, but that the whiteness of the paper rushes towards my eyes, and my eyes embrace the whiteness like a long-lost friend.”

For Berger, seeing was reciprocal – that is, we may agree that something can be seen but we are often unsure about what we’re looking at. It takes another’s seeing to confirm the qualities of what we’re looking at – even as we each have our own way of looking. As he wrote in Ways of Seeing, “They eye of the other combines with our own eye to make it fully credible that we are part of the visible world.” Cataract is Berger’s amazed reaction to the visual sense that had amazed him for decades. He ends by saying, “And the two eyes, portcullises removed, again and again register surprise.”

[Published by Notting Hill Editions on November 14, 2023, 65 pages, $17.99 hardcover]

To read Ron Slate’s review of Bento’s Sketchbook by John Berger (2011), click here.

To read Ron Slate’s review of Hold Everything Dear by John Berger (2007), click here.