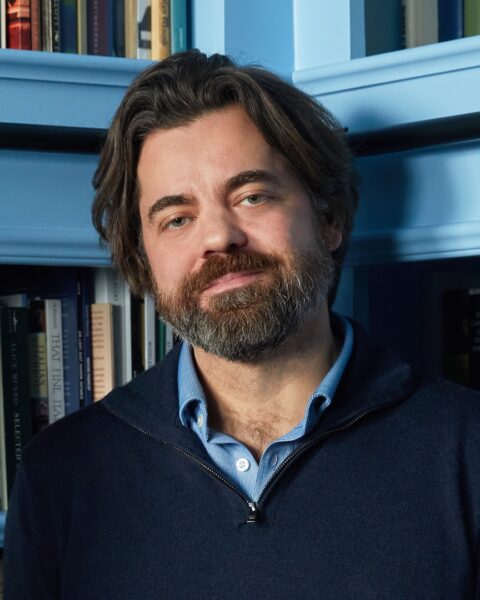

Walking to the microphone with a sheaf of poems instead of a published book, V. Joshua Adams was something of a mystery to the New Orleans regulars who packed Saturn Bar in August, 2023. Most of us were there simply because we put trust in the Splice Reading Series, whose curators have cast a wide net in recent years, showcasing poets as different as Rodger Kamenetz, Sandra Simonds, Karisma Price, Carolyn Hembree, Alina Stefanescu and Rodney Jones.

But what about Adams? Would this lively Twitter presence and Louisville prof give us tidy confessions from academe, doctrinare politics, Language School retreads — or some other echo of MFA-era poetics? With no book in hand, one could only guess.

We needn’t have worried. In his lively 30-minute reading, Adams offered taut lyrics and expansive narrative poems that gained amplitude by holding their subjects at arm’s length. Even in a barroom setting, Adams was able to drive home the many virtues of his poems: vowels and consonants set to an inner music that underscored meaning and welcomed fresh mysteries; cascades of language, sweeping listeners through narrative twists; comic asides unleashed with vaudeville panache. That night, Adams wasn’t echoing anyone. He gave his audience counter love, original response and prompted some to pre-order Past Lives, his debut collection, which JackLeg Press would eventually publish in July, 2024.

We needn’t have worried. In his lively 30-minute reading, Adams offered taut lyrics and expansive narrative poems that gained amplitude by holding their subjects at arm’s length. Even in a barroom setting, Adams was able to drive home the many virtues of his poems: vowels and consonants set to an inner music that underscored meaning and welcomed fresh mysteries; cascades of language, sweeping listeners through narrative twists; comic asides unleashed with vaudeville panache. That night, Adams wasn’t echoing anyone. He gave his audience counter love, original response and prompted some to pre-order Past Lives, his debut collection, which JackLeg Press would eventually publish in July, 2024.

Fair warning: Even in print, Adams remains a bit of a mystery. He’s charming, but private — like the life-of-the-party who prefers to go home alone, a tad rueful, perhaps, but happy to tend his ironies under a desk lamp with pen in hand.

Yet, despite Adams’ reserve, Past Lives offers some biographical hints. In a comic passage from “Lotus,” for example, the poet reveals both his teaching style, and his self-mocking ease with an audience:

There are things we now know.

A woman may play

bagpipes expertly next to

a statue of Jimmy Page.

The potato pancakes taste

like cigarettes and the

cigarettes taste like artichokes

and the artichokes taste

like mild regret.

And what does the student know after sampling such verse? Surely, that Adams’ lines spring down the page with a tap dancer’s elan; that his patter-driven narratives can quickly swing from surreal whimsy to mature remorse.

In “Discourse on Method,” Adams spins a retrospective fiction, sustained by a first-person voice. We’re told of two young beachgoers who sit “cross-legged on the cement in La Spezia,” most likely grad students on holiday, quite possibly in love, but certainly touched by travel-induced ennui and the habit of overthinking. Their desultory exchanges include queries about The Edict of Nantes, a shared hope that the upcoming train to Pisa will be air-conditioned, and much philosophic chatter:

I remembered Descartes’ argument

concerning God’s perfection and goodness,

that these were a sort of trancendental insurance policy

guaranteeing all our knowledge

in the event of an accident, like an accidental doubt

of God’s perfection and goodness,

something that might just happen someday

like a tree limb falling through the top of an old cabriolet

and marring the sheepskin seat covers.

When the “I” appears in Adams’ poems, it’s not to offer the stamp of emotional authenticity, but to take advantage of the many masks that a skilled raconteur can adopt. If Adams opens his wounds, he never displays them publicly, preferring to lead readers astray in a dark funhouse of references, points of view, wordplay and plot twists. Tellingly, he avoids the material that many poets would tap automatically. Here you won’t find mention of Adams’ marriage, his children, his parents, his health, his politics, his French and Italian fluency, his translations and reviews, or his blue chip education, which culminated with a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago.

For many readers of Past Lives, the salient biographical detail will be the book’s long gestation. Adams spoke about that in a recent interview with Variant Literature: “The oldest poem in the book is ‘Bohemia Bagel,’ which has its origins with me being in Prague in the summer of 2003 at a place called Bohemia Bagel, reading John Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror — 21 years ago.”

For many readers of Past Lives, the salient biographical detail will be the book’s long gestation. Adams spoke about that in a recent interview with Variant Literature: “The oldest poem in the book is ‘Bohemia Bagel,’ which has its origins with me being in Prague in the summer of 2003 at a place called Bohemia Bagel, reading John Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror — 21 years ago.”

During a fact-check call for On the Seawall, Adams added that “Bohemia Bagel” began life as six finished poems which he molded into one piece over the decades. The resulting collage still brims with touristic particulars. It features shops full of handbags and chocolate, Prague waiters, some “serpent-peppered maps with their winged ships / buoyant as the overture to the Zauberflöte,” and a lone dental assistant who exits a gilded art nouveau elevator and offers “a most frankly appraising look, top to toe, widely smiling.” But the poem is more than a bundle of old snapshots. From his youthful observations, Adams has crafted a 49-line, autumnal palimpsest, one that embosses a young a traveler’s elation with the Old World melancholy of Mittel Europa — even as it hints at the poet’s own middle-aged woe. In its closing lines, the poem fades, as life often fades, with some sighing, disabused observations, worthy of Ashbery himself:

Like tennis or chess, it’s doubtful you will become a master,

but the cultivation is the thing

or at least the sound of the word cultivation

as you repeat it silently to yourself in the supermarket.

Past Lives also rewards with a host of short, lapidary works that demand close reading. Poems such as “Revisionary Ratios,” “Letter to the Corinthians,” and “After ‘Marie Antoinette’” work their magic via dream association, nonsensical word play, copious rhyming, and something akin to Mallarmé’s mad faith in the abstract, purely musical qualities of language. Such experiments don’t always work in English — maybe we’re too impatient — but in Adams’ densely packed lyrics the willing reader gets a taste of the true French vintage. Here’s how it works in “After ‘Marie Antoinette’” an ekphrastic poem inspired by Sofia Coppola’s 2006 biopic about the French Queen:

First chum, then semaphore,

until at last the crosshair

grid goes dark.

Buried key, our liquid

pleas are bricked

knee-deep with hush,

the abject flush of palm

to eye says such, that trust

alone won’t translate into reach.

We preach. But where,

and out of what relief?

Signs flank the pilgrim girls

in their square feet

and fork the path to pollen,

then to tree. Champagne

shadows sailed the privy walls

to scald the hair of those

who sewed your fleur de lis.

Spit guaranteed this loan

could not be called

until lips were currency.

In such poems, Adams serves the same intoxicating draught that Ashbery and his modernist predecessors once sipped in Paris. His work is for readers who disdain the fresh-squeezed benefits of American horticulture — all that natural stuff that goes down easy and suits our national fetish for health and authenticity. Instead, Adams brims the glass with daring artifice. He’s a perfect host, happily uncorking the bottles of literary form, those spirit vessels wherein our loves and losses, our daily commonplace, our ticking sense of duration are converted, by slow fermentation, to the wine of infinitude.

[Published by JackLeg Press on July 15, 2024, 71 pages, $18.00 paperback