on Bernd & Hilla Becher, edited by Jeff L. Rosenheim

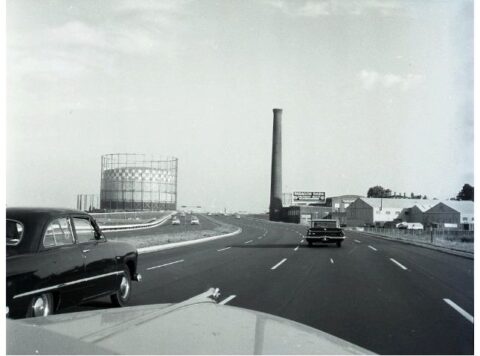

I grew up in Quincy, MA, just south of Boston, but my mother’s relatives, whom we visited regularly, lived north of the city. On Sundays, my father’s Chrysler would carry us through Dorchester, South Boston, Charlestown and Everett up to Malden. Landmarks became familiar, even as outmoded buildings were razed and America’s space-age economy erected new marvels. One notable example of industrial scale was the venerable Boston Gas tank, built in 1923 on Commercial Point, replaced in 1971 by a sleek LNG tank famously splash-painted by Corita Kent. But it was the original tank that captivated me with its exoskeletal steel framing and the portly vessel, decorated atop with a checked belt, contained within it. The tank was just the sort of structure sought after by Bernd and Hill Becher who in 1959 began shooting the rusting and soon to be demolished industrial architecture that serviced the booming post-WWII economies of Europe and North America.

I grew up in Quincy, MA, just south of Boston, but my mother’s relatives, whom we visited regularly, lived north of the city. On Sundays, my father’s Chrysler would carry us through Dorchester, South Boston, Charlestown and Everett up to Malden. Landmarks became familiar, even as outmoded buildings were razed and America’s space-age economy erected new marvels. One notable example of industrial scale was the venerable Boston Gas tank, built in 1923 on Commercial Point, replaced in 1971 by a sleek LNG tank famously splash-painted by Corita Kent. But it was the original tank that captivated me with its exoskeletal steel framing and the portly vessel, decorated atop with a checked belt, contained within it. The tank was just the sort of structure sought after by Bernd and Hill Becher who in 1959 began shooting the rusting and soon to be demolished industrial architecture that serviced the booming post-WWII economies of Europe and North America.

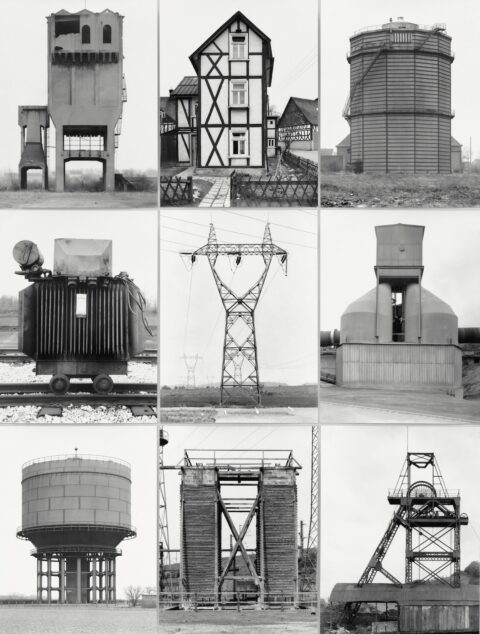

They didn’t photograph their subjects — water towers, storage tanks, factories and smokestacks, grain silos — out of nostalgia nor, unlike photographers today, to document or critique harsh conditions faced by laborers. Never including people and always showing their objects before a blank overcast sky casting no shadows, the Bechers weren’t exactly documentarians nor did they ever suggest that their meticulous images were fine art. They eliminated any effects that would cast a scenic or charming glow. There was no implied message to preserve the architecture. But the minimalist modesty of their work ultimately earned them the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 1990, the show’s most prestigious honor. The Bechers worked with a large-format 13×18 cm Plaubel camera on a tripod, disregarding the 35mm camera and the art market’s rage for color.

I discovered their work in 1993 when the MIT Press published Gas Tanks (also released by Schirmer/Mosel Verlag in Germany at that time). When one opens the book, the introduction immediately states, “Gasholders (colloquially, ‘gas tanks’) are containers for coke, natural gas, and other gases. They provide temporary storage that allows supply and demand to be balanced in municipal gasworks and industrial plants.” There is no artist’s statement. I became engrossed in the images. Why? What is it about their compositions that invites us to keep looking? Was I simply responding nostalgically, recalling my vanished Boston Gas tank?

“Cooling Tower, Caerphilly, South Wales, Great Britain,” 1966, Gelatin silver print, 14 5/8 × 11 3/4 in. (37.1 × 29. 9 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of the LeWitt Family, in memory of Bernd and Hilla Becher, 2018 (2018.618.1) © Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher

Looking at the Bechers’ photographs one after the other, I see “a meticulously consistent point of view and perspective,” as Jeff L. Rosenheim says in his introduction, “one that generally eliminated all but a modest suggestion of scale and environmental context for the buildings in the pictures.” Each object seems unwaveringly individual among other individuals, even as format and category are predetermined. Just as minimalist artist Sol Lewitt made his art out of basic formulae of his own choosing, the Bechers “used an almost Linnean system of classification in which each photograph is treated like a botanical or zoological specimen.” In 1963, the Bechers hung their first show at a gallery in Siegen, Germany. Five years later, their work was featured in Architectural Forum and in a solo show at the School of Architecture and Fine Arts at the University of Southern California. “Bernd was arguably then world’s most important teacher boy photography in the last half-century,” asserts Rosenheim, noting that younger photographers such as Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Thomas Ruff and Andreas Gursky all embraced the Bechers’ rigorous approach.

“Comparative Juxtaposition, Nine Objects, Each with a Different Function,” 1961–72, Gelatin silver prints\ , each 9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.1 × 19.1 cm), mount 38 × 30 in. (96.5 × 76.2 cm) , The Daniel and Estrellita Brodsky Family Foundation Gift, and David Hunter McAlpin Fund, by exchange, 2022 (2022.165) © Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher

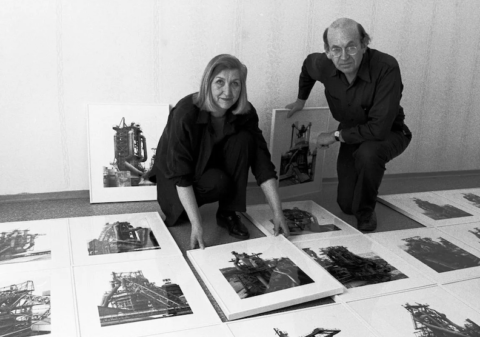

But there is a crucial difference between the Bechers’ work and Lewitt’s wall drawings. The Bechers peered directly at a world in decline — its lines, shapes, and stature. Bernd & Hilla Becher is informed and enlivened by three contextual essays contributed by Virginia Heckert, Gabriele Conrath-Scholl and Lucy Sante. Heckert quotes them: “We prefer to leave the concept of art open. Creativity can be found in any discipline and creativity is about expanding boundaries.” Nevertheless, and like the Oulipians in literature, the Bechers insisted on strict guidelines. For instance, they focused on specific kinds of structures with forms that reveal function. Heckert says that “each type needed to have a continuous history of development that demonstrated variations int form over time.” There were also special projects — such as the Concordia Mine project, detailed in Conrath-Scholl’s essay. Finally, in “A Postmortem for Industry,” Lucy Sante places the Bechers within the history of industrial imagery: “The Bechers’ work will be the final memorial to this epoch, a cenotaph that by extension honors the millions of lives conducted within, around, and in the shadow of their outsize and unmourned objects.”

Bernd Becher (1931-2007) and Hilla Becher (1934-2015) led me back towards my youth with an eye for the actual and its guaranteed demise — not to mourn the Boston Gas tank with “remember when?” but to situate my memory within the global dissolution of ingenious objects.

Bernd Becher (1931-2007) and Hilla Becher (1934-2015) led me back towards my youth with an eye for the actual and its guaranteed demise — not to mourn the Boston Gas tank with “remember when?” but to situate my memory within the global dissolution of ingenious objects.

[Published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art on August 2, 2022 and distributed by Yale University Press, 282 pages, 217 duotone illustrations, $65.00 US]

/ / /

on The Greatest Evil is War by Chris Hedges

“War is only a cowardly escape from the problems of peace,” wrote Thomas Mann, sounding a lot like Ronald Reagan who said, “Peace is not the absence of conflict. It is the ability to handle conflict by peaceful means.” Conflict abides, from the self-hate of the unloved to the state-hate of rival nations. Reagan’s epigram suggests that the skillful management of a simmering conflict, precluding its eruption into war, is the job of an American president. But our innate capacity for violence and the persistence of daily conflict aren’t the root causes of war, according to journalist Chris Hedges. He indicts the “warmongering pundits, foreign policy specialists, and government officials … pimps of war, puppets of the Pentagon, a state within a state, and the defense contractors who lavishly fund their think tanks.” Reagan’s military support to El Salvador’s and Guatamala’s murderous regimes, as well as his support of Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist Iraq during its war with Iran, reveal a president disinterested in “peaceful means.”

This was the lead headline on my Reuters feed on November 24, 2022: “Prague/Warsaw – Europe’s arms industry is churning out guns, artillery shells and other military supplies at a pace not seen since the Cold War.” The CEO of Poland’s state-owned PGZ (Polish Armaments Group) beamed, “There is a real chance to enter new markets and increase export revenues in the coming years,” adding that the conglomerate will double its investment in new facilities. Markets and revenues … the profit motive for war doesn’t bother to hide its face. Last May, the U. S. Congress approved $19 billion for immediate military support to Ukraine with more aid coming.

This was the lead headline on my Reuters feed on November 24, 2022: “Prague/Warsaw – Europe’s arms industry is churning out guns, artillery shells and other military supplies at a pace not seen since the Cold War.” The CEO of Poland’s state-owned PGZ (Polish Armaments Group) beamed, “There is a real chance to enter new markets and increase export revenues in the coming years,” adding that the conglomerate will double its investment in new facilities. Markets and revenues … the profit motive for war doesn’t bother to hide its face. Last May, the U. S. Congress approved $19 billion for immediate military support to Ukraine with more aid coming.

Hedges has told us all about this before in his books, starting with his best-selling War Is A Force That Gives Us Meaning (2002) and continuing with Collateral Damage (2008) in which interviews with Iraq combat veterans uncovered the atrocities inflicted by American soldiers. In his new book, The Greatest Evil Is War, comprising sixteen brief essays, the shock of his experiences as a war correspondent in Central America, the Balkans, Africa and the Middle East arises anew. In these stark, blunt essays, Hedges hews to his singular message – and if the polemical assertions become repetitive, they repeat out of passion, not poor editing. By giving each essay at a slightly different sub-topic, he adds various aspects of his argument – the evolution of a conscientious objector in “The Soldier’s Tale,” the suicidal urges of returning vets in “Wounds That Never Heal,” the manipulation of the American populace in “War Memorials,” the motives and instincts behind “Permanent War.” In the latter, he acknowledges the “powerful yearnings for death and self-immolation” feared by Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents – just as for Hedges, who has seen the corpses and body bags, our task is to restrain our evil desires. Permanent war, he believes, ”is finishing off the liberal traditions in Israel and the United States.”

The essays are collected from among those written for Truthdig and ScheerPost over the past two decades. In 2003, Hedges gave a commencement address at Rockford College in Rockford, Illinois in which in which he denounced the American occupation of Iraq. After his employer at the time, The New York Times, reprimanded him, Hedges resigned. But he has inspired other journalists to continue reporting on our war industry, the actualities of combat, and the ruination of lives. Consider this recent article by Chris Blattman in Boston Review, “The Roots of War,” in which “five reasons for war” are named.

The essays are collected from among those written for Truthdig and ScheerPost over the past two decades. In 2003, Hedges gave a commencement address at Rockford College in Rockford, Illinois in which in which he denounced the American occupation of Iraq. After his employer at the time, The New York Times, reprimanded him, Hedges resigned. But he has inspired other journalists to continue reporting on our war industry, the actualities of combat, and the ruination of lives. Consider this recent article by Chris Blattman in Boston Review, “The Roots of War,” in which “five reasons for war” are named.

Hedges knows that “there are times – World War II and the Serb assault on Bosnia would be examples – when a population is pushed into war. There are times when a nation must ingest the poison of violence to survive. But this violence always deforms and maims those who use it.” The book’s first sentence reads, “Preemptive war, whether in Iraq or Ukraine, is a war crime” — which then forces us to examine and specify the West’s role in deterring Russia — and coming to terms with the Bush-Cheney Iraq occupation. Clearly, NATO and the U.S. don’t wasn’t to confront Russia directly — and they don’t have to. The Ukrainians will suffer the horrors and after effects of battle spelled out by Hedges, while Lockheed, Boeing, Raytheon and Northrup Grumman submit their invoices to the Pentagon.

“What a country calls its vital economic interests are not the things which enable its citizens to live, but the things which enable it to make war. Gasoline is much more likely than wheat to be the cause of international conflict.” — Simone Weil

[Published by Seven Stories Press on September 13, 2022, 208 pages, $21.95US]

* * * * *