But maybe

in a smokecloud of error

we have

created a wandering cosmos

with the language of our breath —

Have we

time and again

sounded the fanfare

of the beginning

shaped the grain of sand

quick as wind

before, once more, there was light

above the bud of the embryo?

And again

we are encircled

in your districts, and again,

though we don’t recall the night

nor the depths of the sea

with our teeth we bite off

the star-veins of words.

And still we work your field

behind death’s back.

Maybe the detours of man’s fall

are like the secret desertions of meteors

marked in the alphabet of storms

alongside rainbows–

And who knows

the course of becoming fertile

how seeds bend up

out of depleted soil

for the suckling mouths

of light.

/ / /

Aber vielleicht

haben wir

vor Irrtum Rauchende

doch ein wanderndes Weltall geschaffen

mit der Sprache des Atems?

Immer wieder die Fanfare

des Anfangs geblasen

das Sandkorn in Windeseile geprägt

bevor es wieder Licht ward

über der Geburtenknospe

des Embryos?

Und sind immer wieder

eingekreist

in deinen Bezirken

auch wenn wir nicht der Nacht gedenken

und der Tiefe des Meeres

mit Zähnen abbeißen

der Worte Sterngeäder.

Und bestellen doch deinen Acker

hinter dem Rücken des Todes.

Vielleicht sind die Umwege des Sündenfalles

wie der Meteore heimliche Fahnenfluchten

doch im Alphabet der Gewitter

eingezeichnet neben den Regenbögen–

Wer weiß auch

die Grade des Fruchtbarmachens

und wie die Saaten gebogen werden

aus fortgezehrten Erdreichen

für die saugenden Münder

des Lichts.

* * * * *

So it’s said —

drawn in snaking lines

plunge.

The sun

Chinese mandala

divinely warped jewel

turned in inward phases

back home twisting,

smile fixed

in constant prayer

light-dragon

spitting at time

the shield bearer was earth’s wind-fallen fruit

once

scorching-bright gold —

Prophecies

point with flaming fingers:

This is the star

husked to death —

This is the apple’s core

sown in the solar eclipse

so we fall

so we fall.

/ / /

So ist’s gesagt

mit Schlangenlinien aufgezeichnet

Absturz.

Die Sonne

chinesisch Mandala

heilig verzogener Schmuck

zurück in innere Phasen heimgekehrt

starres Lächeln

fortgebetet

Lichtdrachen

zeitanspeiend

Schildträger war die Fallfrucht Erde

einst

goldangegleist –

Weissagungen

mit Flammenfingern zeigen:

Dies ist der Stern

geschält bis auf den Tod —

Dies ist des Apfels Kerngehäuse

in Sonnenfinsternis gesät

so fallen wir

so fallen wir.

* * * * *

For a long time

Jacob

with the blessing of his arm

scythed down

the grain of millennia

hanging in the sleep of the dead —

saw

with blind eyes —

held suns and stars

in his arms

for a bright blissful moment —

till finally all leapt

like birth from his hand

and

into Rembrandt’s celestial eye.

Joseph

still tried

quickly

to deflect

the flash of false blessing

already flaring up

God-knows-where —

And the firstborn went out

like embers —

/ / /

Lange

sichelte Jakob

mit seines Armes Segen

die Ähren der Jahrtausende

die in Todesschlaf hängenden

nieder —

sah

mit Blindenaugen —

hielt Sonnen und Sterne

einen Lichtblick umarmt —

bis es endlich hüpfte

wie Geburt aus seiner Hand

und

in Rembrandts Augenhimmel hinein.

Joseph

schnell noch

versuchte den Blitz

des falschen Segens

abzuleiten

der aber brannte schon

Gott-wo-anders auf —

Und der Erstegeborene losch

wie Asche —

* * * * *

Line like

living hair

drawn

deathnight-darkened

from you

to me.

Bridled

on the outside

I am bowed down

thirsting to kiss

the end of distances.

The evening

is throwing the springboard

of night over the crimson

lengthening your headland

and I place my foot, hesitating,

on the quivering string

of death, already begun

But such is love- –

/ / /

Linie wie

lebendiges Haar

gezogen

todnachtgedunkelt

von dir

zu mir.

Gegängelt

außerhalb

bin ich hinübergeneigt

durstend

das Ende der Fernen zu küssen.

Der Abend

wirft das Sprungbrett

der Nacht über das Rot

verlängert deine Landzunge

und ich setze meinen Fuß zagend

auf die zitternde Saite

des schon begonnenen Todes

Aber so ist die Liebe —

* * * * *

Deep inside

the station of suffering

possessed by a smile

you answer

those

who question in the shadows

their mouths full of god-deformed words

hammered out

from pain’s distant past.

Love no longer wears a shroud,

space is spun

in the thread of your longing.

Stars ricochet

back from your eyes

sunsubstance

softly turning to char

but over your head

Stella Maris, lodestar of certainty,

glows ruby red

with the arrows of resurrection —

/ / /

Inmitten

der Leidensstation

besessen von einem Lächeln

gibst du Antwort

denen

die im Schatten fragen

mit dem Mund voll gottverzogener Worte

aufgehämmert

aus der Vorzeit der Schmerzen.

Die Liebe hat kein Sterbehemd mehr an

versponnen der Raum

im Faden deiner Sehnsucht.

Gestirne prallen rückwärts ab

von deinen Augen

diesem

leise verkohlenden Sonnenstoff

aber über deinem Haupte

der Meeresstern der Gewißheit

mit den Pfeilen der Auferstehung

leuchtet rubinrot —

* * * * *

Behind the lips

the unutterable waits

tears at the umbilical cords

of words

the martyr’s death of the alphabet

in the mouth’s urn

spiritual ascension

out of searing pain —

But the breath of inner speech

through the wailing wall of air

whispers a confession freed of secrets,

sinks into the asylum

of the world’s wound

even in its downfall

still overheard by God —

/ / /

Hinter den Lippen

Unsagbares wartet

reißt an den Nabelsträngen

der Worte

Märtyrersterben der Buchstaben

in der Urne des Mundes

geistige Himmelfahrt

aus schneidendem Schmerz —

Aber der Atem der inneren Rede

durch die Klagemauer der Luft

haucht geheimnisentbundene Beichte

sinkt ins Asyl

der Weltenwunde

noch im Untergang

Gott abgelauscht —

* * * * *

Joshua Weiner on Nelly Sachs

The Jewish-German (naturalized Swedish) poet Nelly Sachs was born in 1891, in the Schöneberg district of Berlin, to a bourgeois and assimilated family. Frail of health and sheltered for much of her childhood, Sachs wrote poems and stories that show the deep influence of German Romanticism, an influence she would later distill and refract through more modernist techniques and perspectives into some of the first powerful responses to the Holocaust in poetry, poems in which she discovered her mature voice as a poet and made her reputation.

As a young woman she absorbed at some remove the fin-de-siècle atmosphere around the Stefan George circle, her poetry and prose appearing in local newspapers including, after the Nuremberg race laws of 1935, Jewish community publications; her marionette plays from this time also found modest production. Sachs never really took much part in the Berlin literary scene around figures such as Gottfried Benn and Bertolt Brecht, but lived in the familiar margin, like most writers, of being both known and unknown. (Readers of German lyric poets such as Gertrud Kolmar and Else Lasker-Schüler may detect some influences there, though Sachs’s later turn from lyric conventions sets her apart.) The story of her narrow escape from Nazi Germany to Sweden in 1940 with the help of close friends in Berlin; the last minute aid of powerful friends from afar (such as the Swedish Nobel laureate Selma Lagerlöf, also an influence on her early writing); and even a sympathetic police officer who told her to avoid the trains, reads like a 1940’s Hollywood script.

As a young woman she absorbed at some remove the fin-de-siècle atmosphere around the Stefan George circle, her poetry and prose appearing in local newspapers including, after the Nuremberg race laws of 1935, Jewish community publications; her marionette plays from this time also found modest production. Sachs never really took much part in the Berlin literary scene around figures such as Gottfried Benn and Bertolt Brecht, but lived in the familiar margin, like most writers, of being both known and unknown. (Readers of German lyric poets such as Gertrud Kolmar and Else Lasker-Schüler may detect some influences there, though Sachs’s later turn from lyric conventions sets her apart.) The story of her narrow escape from Nazi Germany to Sweden in 1940 with the help of close friends in Berlin; the last minute aid of powerful friends from afar (such as the Swedish Nobel laureate Selma Lagerlöf, also an influence on her early writing); and even a sympathetic police officer who told her to avoid the trains, reads like a 1940’s Hollywood script.

The reception of the poems she wrote in the forties, in which she takes on the personae and speaks through voices of the Shoah’s murdered Jews, has a history complicated by the politics of reconciliation (between Jews and Germans) after WWII, East Germany being more receptive than West to grappling with the immediate crimes of the Nazi state; these have also become, paradoxically, the poems most readers know, and the most widely anthologized in English translation. But such poems don’t define the force of Sachs’ oeuvre. A poet whose voice was forged in the Holocaust, she is not a “Holocaust poet” per se, but one who wrote her way through the horror of the Shoah and into a poetry of the eternal refugee, a poetry influenced, as well, by her studies in Jewish Kabbalah. It was these poems of the 50’s and early 60’s that became more widely read in Germany thanks to the advocacy of younger poets such as Hans Magnus Enzensberger; a broader recognition was thereby launched that culminated in her receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature, an honor she shared with the Israeli fiction writer, S. Y. Agnon, in 1966. Sachs died in 1970, the day her dear friend, her “brother” survivor, the poet Paul Celan, was buried.

The poems in this selection are drawn from Sachs’s 1959 volume, Flucht und Verwandlung (Flight and Metamorphosis), which marks the culmination in a period of her development as a poet. (The original order of the poems is maintained here.) In this book-length sequence of poems, Sachs turns from speaking through the murdered of the Shoah to speaking more for herself, her own condition of being a refugee from Nazi Germany—her loneliness living in a small Stockholm flat with her elderly mother, her exile, her alienation, her feelings of romantic bereavement, her search for the divine, even as she sees with visionary power the state of continual flight and asylum-seeking as a historical, political, spiritual, and legendary experience that shapes the lives of Jews through time (although in the period before and immediately after WWII, it was no more an exclusive condition than it is now). In these poems, we hear a Nelly Sachs who is closer to us today than she was 20 or even 40 years ago.

The poems in this selection are drawn from Sachs’s 1959 volume, Flucht und Verwandlung (Flight and Metamorphosis), which marks the culmination in a period of her development as a poet. (The original order of the poems is maintained here.) In this book-length sequence of poems, Sachs turns from speaking through the murdered of the Shoah to speaking more for herself, her own condition of being a refugee from Nazi Germany—her loneliness living in a small Stockholm flat with her elderly mother, her exile, her alienation, her feelings of romantic bereavement, her search for the divine, even as she sees with visionary power the state of continual flight and asylum-seeking as a historical, political, spiritual, and legendary experience that shapes the lives of Jews through time (although in the period before and immediately after WWII, it was no more an exclusive condition than it is now). In these poems, we hear a Nelly Sachs who is closer to us today than she was 20 or even 40 years ago.

/ / /

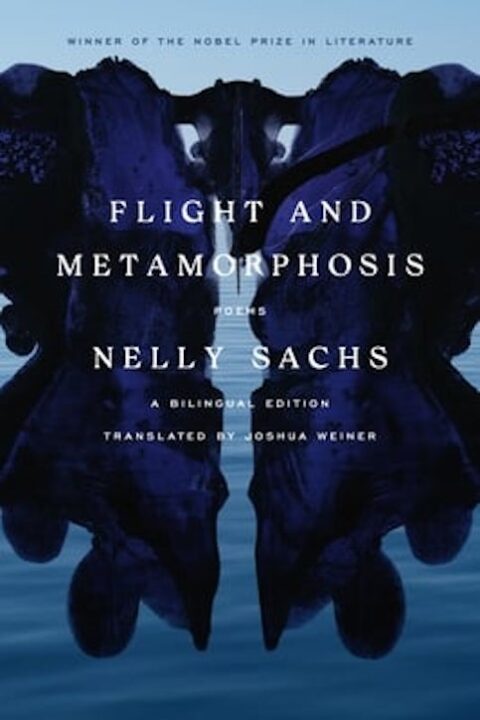

The six poems published here, in German with English translations, appear in Flight and Metamorphosis, poems by Nelly Sachs, a bilingual edition published by Farrar Straus & Giroux on March 14, 2022, translated by Joshua Weiner with Linda B. Marshall. We are grateful to Joshua Weiner for permission to include the poems here with his remarks. You may order the book from Bookshop.org by clicking here.

The six poems published here, in German with English translations, appear in Flight and Metamorphosis, poems by Nelly Sachs, a bilingual edition published by Farrar Straus & Giroux on March 14, 2022, translated by Joshua Weiner with Linda B. Marshall. We are grateful to Joshua Weiner for permission to include the poems here with his remarks. You may order the book from Bookshop.org by clicking here.