If there were three more of me, On The Seawall would have covered the seven titles mentioned below long before now, each of which was published in 2014 and has been on my to-write-about list for months. Before remorse sets in permanently, I’d like to tell you something about the pleasures of these works by Katie Ford, R. A. Villanueva, Fred Moten, Erin Belieu, Dan Chelotti, Peter Streckfus, and Joanna Penn Cooper. (RS)

* * * * * * * * * *

Blood Lyrics by Katie Ford (Graywolf Press)

American poetry today is rife with grievances – but rarely adept at grieving. Katie Ford’s Blood Lyrics issues from the stricken moment when “the mother can’t know / if she counts as a mother.” The prematurely born child may not survive. Although the poems cry out, their plaints don’t appeal for empathy. They seem to rise directly out of the ravaged body with no impulse to reflect credit on the one who feels. Like the child’s life, the language hangs in the balance. This is no topical project book about giving birth and the taking of lives. Both mother and child are discovered and transformed in the wake of trauma. The poems enact a visionary persistence rather than settle for self-elevating description.

LITTLE TORCH

There should have been delight, delight

and windchimes, delight.

But she was clawing the beach

after so much battering,

a torch lit past the slim pine pitch

and draw of resin she was dipped in

at the beginning of the earth.

They said life might flee –

then tended the creature as if a torch,

bundling reeds tightly as day torched

toward them,

soaking rags in lime and sulfur

around barely lit bone.

Such are the wonders I saw.

In the book’s second part, “Our Long War,” the “unbeaten body” of the speaker now peers at bodies less fortunate — dire and depraved situations of which she may be an agent: “If we war there ought to be a sign. / Our lives should feel like cut-outs of lives, / paper dolls drifting to the ground, / ready for chalk outlines.” These speeches are sacraments, chastened but undaunted: “Shot me, said the earth, / like a woman who would not / do it to herself. The ones who heard / convinced her why not, why not / even as they took their sticks / to her in the street. // Shoot me, said the earth. Shoot.” Ford has made instruments out of communal, broken things. Rather than make demands through editorial pieties, she has created a language whose haltings and yearnings make our vulnerability palpable, whether depicted on a hospital gurney or the sites of political violence.

In the book’s second part, “Our Long War,” the “unbeaten body” of the speaker now peers at bodies less fortunate — dire and depraved situations of which she may be an agent: “If we war there ought to be a sign. / Our lives should feel like cut-outs of lives, / paper dolls drifting to the ground, / ready for chalk outlines.” These speeches are sacraments, chastened but undaunted: “Shot me, said the earth, / like a woman who would not / do it to herself. The ones who heard / convinced her why not, why not / even as they took their sticks / to her in the street. // Shoot me, said the earth. Shoot.” Ford has made instruments out of communal, broken things. Rather than make demands through editorial pieties, she has created a language whose haltings and yearnings make our vulnerability palpable, whether depicted on a hospital gurney or the sites of political violence.

[Published October 21, 2014. 80 pages, $16.00]

* * * * * * * * * *

Reliquaria by R. A. Villanueva (Nebraska)

Vividly and unconventionally devotional, at once elegiac and celebratory, Villanueva’s poems are dense with acutely perceived life. His instinct is to praise whatever was sufficiently present to remember — and this includes a whole world in which the very matter that comprises us seems to yearn for something other: “I need you to know I’ve tried. To name ghosts, / to face them, dark as they are, slurred in with / the city’s glossed clots and fresh buttresses, / that earthworks’ trill we’ve let pass for rebirth …” While attuned to and watchful for the breakdowns, Villanueva lures us to remain steadfastly among the materials of living whether promising or not. Belief here has a certain weight – the earnest transit between the sacred and the profane, the centuries of such shiftings bearing down on him.

Vividly and unconventionally devotional, at once elegiac and celebratory, Villanueva’s poems are dense with acutely perceived life. His instinct is to praise whatever was sufficiently present to remember — and this includes a whole world in which the very matter that comprises us seems to yearn for something other: “I need you to know I’ve tried. To name ghosts, / to face them, dark as they are, slurred in with / the city’s glossed clots and fresh buttresses, / that earthworks’ trill we’ve let pass for rebirth …” While attuned to and watchful for the breakdowns, Villanueva lures us to remain steadfastly among the materials of living whether promising or not. Belief here has a certain weight – the earnest transit between the sacred and the profane, the centuries of such shiftings bearing down on him.

BLESSING THE ANIMALS

We have gathered up animals on this feast of St. Francis

to be blessed. In a parking lot beside the church, cleared

save for bales of hay and traffic horses, the goats

and llamas from the petting zoo a town over

are chewing at their cords, the camels’ necks hung

with scapulae. The Elks and Legion men have leashed

border collies to terriers, will garland parakeets with rosaries.

They hold house cats in their arms. Our Monsignor crosses

himself in front of a statue of Jesus and His Most Sacred

Heart, beside the flagpole where I learned to pledge allegiance,

where I will later fold the stars and stripes into triangles

to lock up in the headmaster’s desk. Next month, on my dare,

Howie will throw a bottle of Wite-Out at Christ’s face, break-

off every finger on the Lord’s right hand except his third.

Even the recalled decaying stench of the Meadowlands becomes vital evidence of what appeals to the spirit. “On Transfiguration,” one of several signature pieces, leaps between and connects the raw and ripe elements – a desperately joyous resurrection of the world into words. From “Confluences,” which begins, “Because you will not talk / about your mother’s hands”: “When you gesture at a trash barge, / the sea gulls in their furious circles, I see / a convocation above the heaps, // while cells gathering at the tips / of all her cooled syringes.” Reliquaria is the recipient of the Prairie Schooner Prize in Poetry.

[Published September 1, 2014. 70 pages, $17.95 paperback]

* * * * * * * * * *

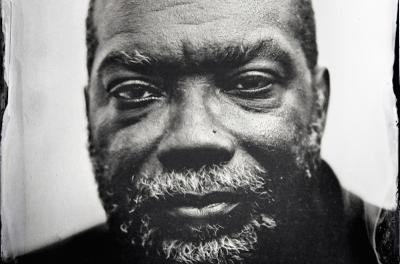

The Little Edges by Fred Moten (Wesleyan University Press)

Fred Moten has noted that Amiri Baraka and Nathaniel Mackey, two of his influences, “find it necessary to make contributions to poetics to ground and justify the kind of deconstructive and reconstructive pressure they put on poetic norms.” His choice of the word “justify” suggests an elevated sense of responsibility. One feels the pressure throughout The Little Edges — in which the edges or boundaries between everything and everyone involved become porous. Here, the relation between poetry and the world (including history) is both topic and technique. Intimacy leads to group dynamics, anecdote runs after philosophy, the oracular tips its hat to the demotic. Moten wants us to have been “composed in listening so we discomposed ourselves in one another.” His poem “Test” begins with citations from Hannah Arendt and journalist Robert McFadden on the breakdown of social relations during an incident on the New York subway system. Then Moten continues:

this is how we never arrive, infuse what we surround to not remember, every day we cross from slave state to

slave state in the barrack cars. We pass by, to avoid examination, in the sun. we were dark to ourselves when

that bird start whistling in the tunnel. Making music we were made to follow, fail to legislate, wouldn’t get off

got off so hard we got off everywhere, our breathing empties the air with fullness and we’re in love in a state

of constant sorrow. The outcome is another process, a way into no way. The refuge is open and can’t be safe.

You must witness the shape of his lines and layout for yourself. He writes, “We care about each other so militantly, with such softness, that we exhaust ourselves, and then record, in the resonance of our slightly opened mouths, the sound of that, in the absence of the enemy that we keep making.” The resonant pronouncements and wordplay are often dazzling, as in the opening lines of “sweet nancy wilson saved frank ramsey”: “The burden is also a refrain. That runs through you. You get no credit / or you get bad credit. Nevertheless, we write ourselves a sound / check.” Moten has said that he is most interested “in the qualities that break and augment and distort the voice.” Spaces open up. Yet when one reads his lines aloud, the voice that emerges from the throat feels and sounds newly whole.

You must witness the shape of his lines and layout for yourself. He writes, “We care about each other so militantly, with such softness, that we exhaust ourselves, and then record, in the resonance of our slightly opened mouths, the sound of that, in the absence of the enemy that we keep making.” The resonant pronouncements and wordplay are often dazzling, as in the opening lines of “sweet nancy wilson saved frank ramsey”: “The burden is also a refrain. That runs through you. You get no credit / or you get bad credit. Nevertheless, we write ourselves a sound / check.” Moten has said that he is most interested “in the qualities that break and augment and distort the voice.” Spaces open up. Yet when one reads his lines aloud, the voice that emerges from the throat feels and sounds newly whole.

[Published December 15, 2014. 79 pages, $22.95 hardcover]

* * * * * * * * * *

Slant Six by Erin Belieu (Copper Canyon)

“Above all things, I am accurate,” writes Belieu in “Perfect,” thus putting her accuracy in doubt, but not for long. Nothing ignites her candor so hotly than pretension. “America, it’s time / to unsuck those bellies / and show our ugly asses,” she writes in “H. Res. 21-1: Proposing the Ban of Push-Up Bras, Etc.” In “When At A Certain Party in NYC,” she gets into a lather over “the Lacanian soap dispenser in the kitchen” and would return by Conestoga to Nebraska “where the other / losers live.” It’s desire that triggers these prickly unmaskings and anticipated demises. Clearly, she relishes the opportunity to abuse any pleasantries, just as Wordsworth surely loved London Bridge (what else to write about?). These are companionable poems (if you enjoy a tart-tongued friend as much as I do) from Belieu’s “Great Middle Period,” mordantly mentioned in “Ars Poetica for the Future.” But to lavish attention on the attitude alone is to scant the rhetorical darting and punchy phrasing of her disquisitions.

“Above all things, I am accurate,” writes Belieu in “Perfect,” thus putting her accuracy in doubt, but not for long. Nothing ignites her candor so hotly than pretension. “America, it’s time / to unsuck those bellies / and show our ugly asses,” she writes in “H. Res. 21-1: Proposing the Ban of Push-Up Bras, Etc.” In “When At A Certain Party in NYC,” she gets into a lather over “the Lacanian soap dispenser in the kitchen” and would return by Conestoga to Nebraska “where the other / losers live.” It’s desire that triggers these prickly unmaskings and anticipated demises. Clearly, she relishes the opportunity to abuse any pleasantries, just as Wordsworth surely loved London Bridge (what else to write about?). These are companionable poems (if you enjoy a tart-tongued friend as much as I do) from Belieu’s “Great Middle Period,” mordantly mentioned in “Ars Poetica for the Future.” But to lavish attention on the attitude alone is to scant the rhetorical darting and punchy phrasing of her disquisitions.

THE BODY IS A BIG SAGACITY

is another thing Nietzsche said

that hits me as pretty specious,

while sitting in my car in the Costco

parking lot, listening to the Ballet mécanique of metal buggies shrieking,

as each super, singular, and self-contained

wisdom of this Monday morning rumbles

its jumbo packs of toilet paper and Diet Coke

up the sidewalk. So count me a Despiser

of the Body, though I didn’t generate this

woe any more than the little man parked

next to me, now attempting the descent from

his giant truck, behemoth whose Hemi roars

like a melting reactor and stands

as the ego’s corrective to the base methods

by which the body lets the spirit down.

Buzz-clipped, tidy as an otter, he’s high and

tight in his riding heels. Pearl snaps on

the little man’s shirt throw tiny lasers

when he passes. But who isn’t more war

than peace? And how ridiculous to suffer

this: to be a little man, with itty hands

and bitty feet, to know yourself lethal, but

Krazy Glued for life to the most laughable

engine. Recycled, rewired, product of

genes and whatever our mamas thought

to smoke: the spirit gets no vote, Fred.

My body once was whole, symmetrical, was

actually beautiful for three consecutive years,

expensive as a rented palace, and yet I blew

that measly era watching my clock hands move,

as if I were the trigger rigged to homemade

dynamite. But if you would look inside me,

into all the lonely seeming folks here loading

their heavy bags, you’d hope we’re something

more than a sack of impulse, of soul defined

by random gristle. Which is why the little man

pauses on the sidewalk, why he stops to look at

me looking at him: this pocket-size person,

whose gaze unkinks a low, hairy voltage from

my coccyx. And thus speaks Zarathustra,

You Great Star,

what would Your happiness be had You not those for whom

ou shine?

Ask the little man, neither ghost nor plant,

his bootheels ringing down the concrete.

The comedic turbulence of the domestic life inspires commentary, an insistence that the materials of even this life can be made into art. An observant distancing that creates an accomplice in the reader. “Poem of Philosophical and Parental Conundrums Written in an Election Year” begins with a child in the backseat saying “Mama, I HATE / Republicans” – a child who has never been heard to say “hate” before – and then weaves its way chat-wise (with a whiff of desperation) through parenthood, divorce, dealing with the ex, liberals and conservatives, evangelicals, the neighborhood, and then concludes: “But with kids, you never know, / as our present is busy becoming / their future, every minute, every day, // while they’re working as hard as they can / to perfect the obstinate and beautiful mystery / that every soul ends up being to every other.”

[Published November 4, 2014. 68 pages, $16.00 paperback]

* * * * * * * * * *

X by Dan Chelotti (McSweeney’s)

In “Reruns” Chelotti writes, “I try to mean more than I can.” Fortunately he fails, but without deconstructing language into a medium of lack and distortion. His poems are sparkling clarities which, like cool glasses of water, don’t promise protein. The boyishness reminds me of James Tate, a bias for tilted situations and modest, quirky involvements. “I love making true things more true, because so often fact is insufficiently true,” Chelotti remarked in an interview – a sanguine foundation since there is something “true” to begin with, made more so by allowing a freed color commentary.

In “Reruns” Chelotti writes, “I try to mean more than I can.” Fortunately he fails, but without deconstructing language into a medium of lack and distortion. His poems are sparkling clarities which, like cool glasses of water, don’t promise protein. The boyishness reminds me of James Tate, a bias for tilted situations and modest, quirky involvements. “I love making true things more true, because so often fact is insufficiently true,” Chelotti remarked in an interview – a sanguine foundation since there is something “true” to begin with, made more so by allowing a freed color commentary.

A PIECE OF MUSIC THAT SOUNDS

LIKE SORROW IS NOT REAL SORROW

I want to do nothing but imitate

the voices of others sometimes

I want to do nothing but imitate

the last thing I’ve read or the song

I’ve just heard so much so I wonder

if I am anything at all

like Piotr Sommer or Lisa Jarnot

whose books are the first books I saw

just now on the shelf next to my desk

which belonged to my great

grandmother who complained

before she died about all the fucking

in the romance novels my mother

would bring her, about how she used

to put candles on the Christmas

trees to risk beauty – that someone should

bring beauty back to the world

or the world might give up

but she didn’t really say any of this

except for the thing about the fucking —

Big topics – art-making, beauty, inheritance – become light, almost weightless, but retain their bigness. Reflective and droll, Chelotti’s engaging, odd intimacies suggest a deep, youthful yearning that quickly hooks the reader: “I wish I could eat a hot dog / when I run around the bases.”

[Published March 26, 2013. 82 pages, $20.00 hardcover]

* * * * * * * * * *

Errings by Peter Streckfus (Fordham)

“A bardo is a boundary between states,” writes Peter Streckfus. The luminous, speculating intelligence of Errings, situated in a liminal state, probes the notion of “my author” – the profound influences of others, as well as the mysterious dwelling of strange energy within oneself – that gather into a radical presence on the page. Cross-genre and multi-textual mixes are often facile in practice and unsatisfying in effect, the easy pretending to be hard. Errings is the collection to study and admire if you’re keen on the integration and variety of texts to create an unpredictable span of thought, in this case, unconventionally elegiac. Streckfus’ father, who died in 2009, wrote an unpublished pirate tale, a “parent text” entitled Two Golden Earrings, appearing here as part of a diverse multi-voiced inquiry on the sources of expression, a call and response over immeasurable distances from worlds entered and left behind – from earrings to errings. The book opens with a poem addressed to and inspired by his wife Heather – and later, “Time Ghazal” speaks to her again:

“A bardo is a boundary between states,” writes Peter Streckfus. The luminous, speculating intelligence of Errings, situated in a liminal state, probes the notion of “my author” – the profound influences of others, as well as the mysterious dwelling of strange energy within oneself – that gather into a radical presence on the page. Cross-genre and multi-textual mixes are often facile in practice and unsatisfying in effect, the easy pretending to be hard. Errings is the collection to study and admire if you’re keen on the integration and variety of texts to create an unpredictable span of thought, in this case, unconventionally elegiac. Streckfus’ father, who died in 2009, wrote an unpublished pirate tale, a “parent text” entitled Two Golden Earrings, appearing here as part of a diverse multi-voiced inquiry on the sources of expression, a call and response over immeasurable distances from worlds entered and left behind – from earrings to errings. The book opens with a poem addressed to and inspired by his wife Heather – and later, “Time Ghazal” speaks to her again:

TIME GHAZAL

There is fire in the beginning – without it, we thought, we could not see one another.

After only months, a scorched foothill, but covered in evergreen heather.

We did not prefer it this way, love, cutting our feet on the stones of the hill as we ascended,

Scratching ourselves among the browns and greens of the heather.

On a sunny morning you fancied you might distinguish with the naked eye the deer that sometimes wandered from adjacent forests,

Or even the hares that began to swarm above the line of heather.

We simply found ourselves here, the ghosts of the grouse, deer, and hares all straying in the morning fog –

Under which we also strayed, the hillside violent in its fog blossom, can you see this, Heather.

You spoke – I listened in my silence, lost in and clinging to it, filled with fear and longing, thinking.

Thinking, come brush the stone of my tongue, grow beside it a flaming branch of heather.

On the northern face, we watched the noon sun light the fog just above the rise,

A small child on the hill, the interior of her heart like a gem, all over flowered with heather.

Streckfus also adapts language from classic eastern texts. In an interview in The Conversant, he said, “Literary history is filled with examples of mixed-form writing, and it tends to occur at points in the development of a literature when the functions of the paragraph and poetic line become revaluated. I’m curious as to why it resurfaces now, when the prose paragraph appears to be matching the poetic line as a means for lyric expression.” Exquisitely artful in every respect, Errings embodies the poet’s long probing of mixed forms, of “writing that talks back to itself,” from Basho to Milosz.

[Published March 3, 2014. 80 pages, $45.00/$19.99 hardback/paperback]

* * * * * * * * * *

The Itinerant Girl’s Guide to Self-Hypnosis (Brooklyn Arts Press) and What Is A Domicile? by Joanna Penn Cooper

A Tennessee childhood in the 1970’s, several decades of a life to consider, but approached warily, without the memoiristic tendency to matter too much and amass self-credit: Cooper finds just the right tone and pitch. As she says, “It’s hard to grow up in poems when you’ve been working on the same project all these years.” The lyric prose pieces and micro-essays of The Itinerant Girl’s Guide to Self-Hypnosis are generous with specificities but relaxed in gesture: “I was born in a town of vegetable gardens, anthropology professors, pregnant teenagers drinking Cokes, and signs in bar windows saying No Indians.” But it is spoken from New York City, the current moment tinted by “my strange combination of pertness and defeat,” a mildly plaintive nervosity. Cooper also recently published What Is A Domicile?, a debut poetry collection with prose mixed in.

A Tennessee childhood in the 1970’s, several decades of a life to consider, but approached warily, without the memoiristic tendency to matter too much and amass self-credit: Cooper finds just the right tone and pitch. As she says, “It’s hard to grow up in poems when you’ve been working on the same project all these years.” The lyric prose pieces and micro-essays of The Itinerant Girl’s Guide to Self-Hypnosis are generous with specificities but relaxed in gesture: “I was born in a town of vegetable gardens, anthropology professors, pregnant teenagers drinking Cokes, and signs in bar windows saying No Indians.” But it is spoken from New York City, the current moment tinted by “my strange combination of pertness and defeat,” a mildly plaintive nervosity. Cooper also recently published What Is A Domicile?, a debut poetry collection with prose mixed in.

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN

I’m writing to inform you of my qualifications on this sunny day inside

wearing silent headphones, a small white feather stuck to one foot.

I can hear that tree clearing its throat outside my fifth floor walk-up.

I can see all this packing and half unpacking of boxes as a compulsive

metaphor for how we’re all of us always moving, always learning

it all the freaking time: How to lose how to lose how to lose.

How to know the dark leather gloss of July leaves and let them go.

How to wear the crown of love and fresh pita for lunch and let it go.

My life is not a plastic hamster ball. My life is not that refugee song.

Not any more than anyone else’s. I’ve cured myself of being

so meta, or else I’ve embraced it. Either way I’m wearing

the crown. Either way, we’re all wearing the crown.

The beginning of “November Dispatch” could also be a description of her mode: “Often in a play, a scene will open on a stage in such a way as to remind you of individual consciousness spreading out into a shared domestic space. A lamp, a rug, a plant. The indication of a heart. A comforting sight and one with a slight frisson of dread.”

[The Itinerant Girl’s Guide to Self-Hypnosis: published February 25, 2014, 60 pages, $15.95 paperback; What Is A Domicile?: published June 30, 2014, 66 pages, $14.00 paperback]