Welcome to the Seawall’s semi-annual poetry feature. This season, eighteen poets write briefly on some of their favorite new and recent collections. This multi-poet/title feature is posted here in April and November. The commentary includes:

Joshua Weiner on Bewilderment: New Poems and Translations by David Ferry (University of Chicago Press)

Evie Shockley on The Vital System by C. M. Burroughs (Tupelo Press)

Nick Sturm on Bright Brave Phenomena by Amanda Nadelberg (Coffee House Press)

Anna Journey on Copperhead by Rachel Richardson (Carnegie Mellon)

Rusty Morrison on To Keep Love Blurry by Craig Morgan Teicher (BOA Editions)

Hank Lazer on If by Leonard Schwartz (Talisman House)

Lisa Russ Spaar on Nine Acres by Nathaniel Perry (The American Poetry Review)

Christopher Merrill on Mara’s Shade by Anastassis Vistonitis, translated from the Greek by David Connolly (Tebot Bach)

Shane McCrae on Fowling Piece by Heidy Steidlmayer (Triquarterly)

Adrian Blevins on Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open by Diane Seuss (Univ. of Massachusetts Press)

Paul Otremba on ROTC Kills by John Koethe (Harper Perennial)

Joni Wallace on Animal Collection by Colin Winnette (Spork Press)

Daniel Bosch on More Pricks Than Prizes by Tom Pickard (Pressed Wafer)

Kelly Cherry on The Swing Girl by Katherine Soniat (LSU Press)

Judith Harris on Mark The Music by Merrill Leffler (Dryad Press)

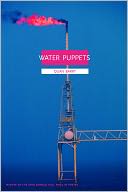

Andrew McFadyen-Ketchum on Water Puppets by Quan Barry (University of Pittsburgh Press)

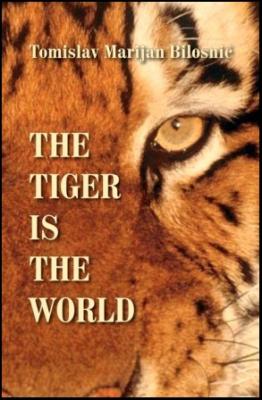

John Taylor on The Tiger is the World by Tomislav Marijan Bilosnic, translated from the Croatian by Durda Vukelic-Rozic and Karl Kvitko (Xenos Books)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Joshua Weiner

Bewilderment: New Poems and Translations by David Ferry (University of Chicago Press)

There is no American poet writing a more American poetry than David Ferry; and by the measure of Bewilderment: New Poems and Translations, Ferry succeeds again in showing how American poetry belongs to the world. The rigor of his plain style, its absolute and flexible command of the poem’s verbal surface and his cunning feel for dramatic repetition of word & phrase, put him in a first class of American plain stylists such as Stein, Hemingway, Frost, and David Mamet. As do they, Ferry has a gift for the artfully artless expression, an instinct for reaching far and going deep by sounding the lower registers of speech — Wordsworth, the subject of The Limits of Mortality (1959), Ferry’s early scholarly work, is perhaps the first strong poet behind this style for Ferry, but its timbre and muscularity have grown, one hears, with the suave & energetic classical translations that have brought him greater recognition.

Alone in the library room, even when others

Are there in the room, alone, except for themselves,

There is the illusion of peace; the air in the room

Is stilled; there are reading lights on the tables,

Looking as if they’re reading, looking as if

They’re studying the text, and understanding,

Shedding light on what the words are saying;

But under their steady imbecile gaze the page

Is blank, patiently waiting not to be blank.

This tableau of reading in solitude may evoke for some the reader in Wallace Stevens’ “The House Was Quiet and the World Was Calm,” where the solitary imagining mind hovering over the book dissolves the boundaries between inside and outside. But Ferry’s feeling for solitude is keen as Coleridge’s, who understands how deeply alone we are in the presence of others, to be the one awake at midnight in a house of sleepers. “In the Reading Room” stages Ferry’s talent for instilling the ordinary with an eerie light, the inanimate with living shadows; and the insight is quietly terrifying, that our intent hermeneutics bring us no closer to understanding than the bright light that illuminates but does not take in. The experience is far from the comprehension of George Herbert’s “Prayer (I)”. If the lamps are like readers, so too are the readers merely lamps. I find Ferry’s anti-mimesis here—the grammatical continuity that characterizes the radical failure of our understanding—to be more persuasive and moving than the most vigorous á la mode post-everything poetics.

This tableau of reading in solitude may evoke for some the reader in Wallace Stevens’ “The House Was Quiet and the World Was Calm,” where the solitary imagining mind hovering over the book dissolves the boundaries between inside and outside. But Ferry’s feeling for solitude is keen as Coleridge’s, who understands how deeply alone we are in the presence of others, to be the one awake at midnight in a house of sleepers. “In the Reading Room” stages Ferry’s talent for instilling the ordinary with an eerie light, the inanimate with living shadows; and the insight is quietly terrifying, that our intent hermeneutics bring us no closer to understanding than the bright light that illuminates but does not take in. The experience is far from the comprehension of George Herbert’s “Prayer (I)”. If the lamps are like readers, so too are the readers merely lamps. I find Ferry’s anti-mimesis here—the grammatical continuity that characterizes the radical failure of our understanding—to be more persuasive and moving than the most vigorous á la mode post-everything poetics.

In Ferry’s poems, what appear to be drab everyday events — looking out the window, for example, and observing how a truck has moved from one spot to another — are loaded with potential to enact figures of existential transformation — to unlock mysteries of living, of our struggle to understand our loneliness, separateness, our condition in time, the pathos of how we feel both bound and boundless. No poet now writing more effectively shows how language and form create psychic experiences of the body in time & space, which include the experience of memory, personal memory and tribal. His is a technical mastery of understatement, a forceful eloquence stripped of rhetoric, complete formal actions that fictively reveal the summation of souls. Other poets — John Koethe comes to mind — may be likewise committed to the philosophic/poetic possibilities of plain speech as a mode of thinking; but Ferry’s talent for lyric form create strong supple bodies where others do not; his poems have the irresistible surge of coursing water that threatens to but never overruns its banks.

And I love what the river of poetry carries along in this book: the powerful subtle portraits that readers of Ferry have come to expect; the pungent critique of self-regard that fuels lyric; heartbreaking powerful elegies to his wife, the scholar, Anne Ferry; the range of translations (Rilke, Catullus, Cavafy, Montale, the Anglo-Saxon Bible, and passages from his translations of Horace and Virgil that pick up and amplify themes in the other poems). But special mention should be made of his discursive responses to poems by his friend, the scholar Arthur Gold: collected in one section, each of the five poems by Gold — dramatic meditations on his own illness and mortality — are followed by Ferry’s loose blank verse, that pick up images, ideas & feelings, in a kind of midrashic extension of Gold’s originals, included in full. By foregrounding poetic response as such, the Gold poems concentrate an essential quality and generosity of Ferry’s poetry (that he makes space, first of all, to preserve, in his own book, the otherwise little known poems of a friend, just as he makes a place there for the great ancients & moderns). Thinking, for example, about an image in one of Gold’s poems, of “a darkness so total / That even had there been children outside the bus / And even had they reached to touch the windows with their hands / We would have seen nothing, / We would not have known they were there,” Ferry wonders about the strangeness of the image, and how “the grammar allows those in the bus / To have their vision and not to have it too / As with our every moment of being alive.”

And I love what the river of poetry carries along in this book: the powerful subtle portraits that readers of Ferry have come to expect; the pungent critique of self-regard that fuels lyric; heartbreaking powerful elegies to his wife, the scholar, Anne Ferry; the range of translations (Rilke, Catullus, Cavafy, Montale, the Anglo-Saxon Bible, and passages from his translations of Horace and Virgil that pick up and amplify themes in the other poems). But special mention should be made of his discursive responses to poems by his friend, the scholar Arthur Gold: collected in one section, each of the five poems by Gold — dramatic meditations on his own illness and mortality — are followed by Ferry’s loose blank verse, that pick up images, ideas & feelings, in a kind of midrashic extension of Gold’s originals, included in full. By foregrounding poetic response as such, the Gold poems concentrate an essential quality and generosity of Ferry’s poetry (that he makes space, first of all, to preserve, in his own book, the otherwise little known poems of a friend, just as he makes a place there for the great ancients & moderns). Thinking, for example, about an image in one of Gold’s poems, of “a darkness so total / That even had there been children outside the bus / And even had they reached to touch the windows with their hands / We would have seen nothing, / We would not have known they were there,” Ferry wonders about the strangeness of the image, and how “the grammar allows those in the bus / To have their vision and not to have it too / As with our every moment of being alive.”

Is their reaching out imploring? Imploring

To be born, or tell us something, something

They know we know but that we do not know

In the way that in that other dimension, before

The event of birth or after the event of death,

They know it, though when they’re born they will

Be innocent of what it was they knew?

In these convincing, poignant experiments in poetic essay and homage, convolution becomes revolution: every turning is a verse that stages and erases human presence. Poetry being a time art, Ferry exploits its formal resources to embody this paradox of being, as a being, avant. Yes, Ferry’s translations help keep alive some of the greatest poetry of the past; and his own terrific poems have absorbed that past and grown up from its fundament; but in the Gold poems he adds something equally important by suggesting how poetry, by anyone, is to be valued as a kind of necessary expressive human document. There’s a seriousness, vulnerability, and fierce nobility in this subtle, complex, and tightly interwoven body of work that I sorely miss in much of the poetry being written now. An exemplary artistry, so confident and sure-footed, would be nothing if it couldn’t also make us feel, as a great dancer does, those moments when the body succumbs to gravity. Ferry’s is such a book; it’s a killer, with a long reach that touches us with its keen intuitive feeling for mortal limits.

[Published September 14, 2012. 113 pages, $18.00 paper]

Joshua Weiner is the author of two books of poems and the editor of a collection of essays on the poet Thom Gunn. His new book, The Figure of a Man Being Swallowed by a Fish, will be published by Chicago in spring 2013. A recipient of the 2012 Amy Lowell Poetry Traveling Scholarship, he is currently living in Berlin.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

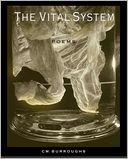

Recommended by Evie Shockley

The Vital System by C. M. Burroughs (Tupelo Press)

I waited for The Vital System for a good while, though not by that name. If asked, I would have said simply that I was looking forward to seeing a collection by C. M. Burroughs, whose work I had read only in small bursts. I imagined that her tightly controlled language, make-you-blink images, and ultraviolet emotional registers would only be more powerful within the larger context of a book, and I am happy to report that I was right.

Burroughs’ first volume of poetry is a sustained and involving exploration of three of the speaker’s relationships: one with her sister, one with her lover, and one with herself. Each is a potent mix of sorrow and need, disappointment and hope, made tangible by way of the possibilities, limits, and betrayals of the body. We learn that the speaker — whom one is tempted to conflate with Burroughs herself, as I will unjustifiably permit myself to do herein—is in an ongoing state of mourning for her sister. She parses the quality of this condition for us in “Think Away the Blood,” a two-part poem whose first section comprises small, fragmented tercets, and whose second part, which I quote here, is prose:

Burroughs’ first volume of poetry is a sustained and involving exploration of three of the speaker’s relationships: one with her sister, one with her lover, and one with herself. Each is a potent mix of sorrow and need, disappointment and hope, made tangible by way of the possibilities, limits, and betrayals of the body. We learn that the speaker — whom one is tempted to conflate with Burroughs herself, as I will unjustifiably permit myself to do herein—is in an ongoing state of mourning for her sister. She parses the quality of this condition for us in “Think Away the Blood,” a two-part poem whose first section comprises small, fragmented tercets, and whose second part, which I quote here, is prose:

Driving to Virginia, with the destination of your grave, I drive into a doe. The eyes bulb gently in their sockets; wide ears bend toward my bumper. Bone and body slam against the undercarriage. Your birthday, nine years after your death. It is 5 AM. I spend the remaining six hours thinking of that body splayed in the road. How long dead. How I travel to you with blood.

This passage illustrates Burroughs’ ability to describe the horrific in terms that render it bearable and unbearable at once. Focusing us first on the soft and beautiful aspects of the doe, which remain soft and beautiful even in the trauma of impact, she is able to shift seamlessly into the more violent images of the wrecked body and the blood that represents the repeatedly reopened wound of her sister’s death. The poem does not explain what ended the sister’s life so early; Burroughs withholds such details, even as she ensures that we feel fully the force with which death enters life. She is thus never in danger of being dismissed as “confessional,” even as her unflinching, economical phrasing steers her clear of sentimentality.

The recurring “he” of the poems, the speaker’s lover, is an emotional lightning rod and a moving target. Sometimes he explodes into an army of men:

I rode the shoulder of my poem, wanting to see

their faces, none specific, all malevolent, calling out

last moments in ridiculous language—love, affection,

tender, one screamed. Not loudly enough and too late.

I wore red paint, salvaging neither plated breast,

nor firm mouth. Not once was I tender.

I wanted them wasted—him, him, him, him, him

Sometimes “he” becomes “she,” a sign of his and Burroughs’ potential for connection:

Suddenly, you had a woman in you. I. Who loved. Who

wanted loved. You and she hyphened between layer-

shucked, glow-wrought. Spoon fed syllables under the

phasing moon. She called you gratitude. Seeing, seen.

Something given. Pocketed in the jaw, stored, hoarded —

you and she, linked in the grammar of —

These passages demonstrate the way her love of language fuels and shapes her passions, whether anger or adoration. We also see the fluidity with which she moves between the real and the imaginary, suggesting how utterly weak are the boundaries between lived experience, dream, and desire. But certain realities cannot be circumvented by love, such as the loss of her sister and the ability of racism to penetrate into one’s most intimate relationships. Burroughs, who is African American, traces the complexities of the latter in a compelling poem titled “The Power of the Vulnerable Body,” from which this passage is excerpted:

. . . Like a man in the female outhouse, he and I tried to hurt

each other

so that the public could not break our skin; we used our canines/birdshots/

live matches/

rope. We wanted to do everything that could be done to us. We used

Nth words,

which did swift damage. There was a gash where he said “[

!]”

Thankfully, he could sew. I was all new within the week except for the

weeping.

The bracketed blank marks the pain without reproducing it, another example of Burroughs’ control over her craft. These lines, like so many others, employ images of bodily vulnerability to illustrate the depth of the lovers’ bond and the consequent threat they pose to one another.

The bracketed blank marks the pain without reproducing it, another example of Burroughs’ control over her craft. These lines, like so many others, employ images of bodily vulnerability to illustrate the depth of the lovers’ bond and the consequent threat they pose to one another.

Burroughs’ poetry is also very much about the threat she poses to and affection she holds for herself. Indeed, poetry, like therapy, offers her ways to be both honest and kind as she negotiates the tricky terrain of her interiority. But this is not poetry as therapy—these poems are too aestheticized and intellectual to serve a primarily clinical purpose. Consider the prose poem “Nights’ Large Fears,” presented below in its entirety:

Hawkweed jimmies window seals. Room for a man whose liquor eclipses him. Beg quiet the body. Fight.

/strike

softly, impact nothing. Even your dream, a woman who allows a woman to die. Leaving from or for the world, prayer beads’ iridescent yes/no.

Never admit that the poet in you might use it. Wait, as you are cut into, long enough to draw the body’s pre-break, the red core’s praxis. Drafts of self and self. Deleting.

The poet does use it: ruthlessly and lovingly recasting her fears— of her body’s betrayal, of her powers of destruction, of her ability to deploy the artist’s canny response to her own deepest wounds — as poems. The poems propose ways in which she, the speaker, might be seen and understood: as weak, powerful, or both. They do so without ever giving up their status as art. The language is full of music, from the traces of black Southern rhythms of speech (“Beg quiet the body”) to the assonance and consonance that drive and conspire with them (“Room for a man whose liquor eclipses him”). Rather than pulling poetry into the realm of therapy, Burroughs reconceives self-definition as art, producing and, at times, deleting various “drafts” of her self.

Although I haven’t discussed the moments of humor in the text, there are many, grounded in delightful wordplay, even in poems that treat her hardest subjects. Burroughs is endlessly inventive in her array of images, expansive in her attitude toward lexicon, and catholic in her approach to form. The umbrella under which she gathers her poems encompasses vast social issues and piercing personal concerns, keeping the reader unsettled in the best possible way. The Vital System’s surprises encourage a rapid first reading; its nuances repay the additional readings it urges and deserves. I am already anticipating Burroughs’ second collection, but will be happily occupied with the first while I wait.

[Published October 31, 2012. 63 pages, $16.95 paper]

Evie Shockley’s most recent book of poetry is the new black (Wesleyan, 2011). Her critical book is titled Renegade Poetics: Black Aesthetics and Formal Innovation in African American Poetry (Iowa, 2011).

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

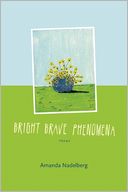

Recommended by Nick Sturm

Bright Brave Phenomena by Amanda Nadelberg (Coffee House Press)

Bright Brave Phenomena is a system of resilient, big-hearted machines, the warm chaos of the light in the grass, or the grass in the light, a field of slightly glitched musics tending to the terrible loveliness that makes us human. It is difficult to leave these poems not feeling a determined YES resonating off everything’s skin, the trees, the people, the windows, the mountains, asking that we be friends, at least for now, at least while we’re being and being breathtaking. Built around direct statements illuminated by a fair amount of semantic wobble, these poems take in and redefine the world, often turning those definitions over until the poem discovers some little piece of joy or sadness it allows the reader to dance with, feeling complicated and hugged. The book’s first poem, “Like a Tiny, Tiny Bird that Used to Make Us Happy,” is an appropriate entrance into Nadelberg’s sense of motion and emotional momentum, making connections that are as subtle as they are expansive, often related to our capacity or incapacity to love. The poem ends:

The lake

and fields quiet broken for winter

but you are still worth thinking, and so

in the tiny century of my mouth

I see you sitting in a window holding

forth, charming the backpacks right

into the night. There were no thoughts

before feet appeared, there was no

time for mapping. The floor of the river

answered the phone, took a message –

the fire smelled of peanuts, the telephone

of stars – it was forever ago dear friend,

you beast, and still I won’t let go.

Propelled by a tender attention that resists anything being inconsequential, the poem, a world inside the world of language (“in the tiny century of my mouth / I see”), delights in its buoyant movements, establishing a logic based on wonder and emotional truth that asks, as desperately as it does joyfully, how is it we can touch the world knowing we cannot hold on to anything. “I say things / because I’m going to lead you to a place and / when we get there it will be so sad,” she writes in “Our Situation,” but this sadness is to be shared, reveled in, recognized as how we know we’re human. It is the door to a pleasure these poems defiantly insist upon believing in, as the poem continues: “We are a lot of / clapping here. So you don’t like flowers? / Fine. Hideous people can have each other, / I don’t care. I just don’t want to be / the assassin. It would kill the mice.”

A search for compassion and empathy is the primary emotional current in Bright Brave Phenomena, continually enacted in moments of simple connection, kindness, and hope: “The telephone is nothing without / friendship” (from “Powerage”), “I will pour two glasses. I will / give you the bigger one” (from “Regardless of Rivers, Aggression in the Driveway is Unlovely”), and “I’m sorry this package does not contain / tiny horses, next time, friend” (from “Recommendation or Decision”). Indeed, these poems create a sense of intimacy between speaker and reader that not only validates the emotional accuracy of our shared confusion, but also suggests that the willingness to acknowledge our wounds as sources of laughter and light is, ultimately, what will save us. “[P]eople are shit shows of fright,” Nadelberg writes in “The Moon Went Away,” but it is “[t]ime for all the what you want, darlings, / darlings, take the fear from your mouths / and listen, blow on the loveliest lamps.” And in the midst of these poems’ well-lit party are the traces of an excellent soundtrack, including references to Springsteen, Dylan, AC/DC, and Stevie Nicks, confirming that these poems aren’t willing to be so serious they forget the music, beyond poetry, that lifts and rescues us daily. From “Here in the Space-Time Continuum”:

A search for compassion and empathy is the primary emotional current in Bright Brave Phenomena, continually enacted in moments of simple connection, kindness, and hope: “The telephone is nothing without / friendship” (from “Powerage”), “I will pour two glasses. I will / give you the bigger one” (from “Regardless of Rivers, Aggression in the Driveway is Unlovely”), and “I’m sorry this package does not contain / tiny horses, next time, friend” (from “Recommendation or Decision”). Indeed, these poems create a sense of intimacy between speaker and reader that not only validates the emotional accuracy of our shared confusion, but also suggests that the willingness to acknowledge our wounds as sources of laughter and light is, ultimately, what will save us. “[P]eople are shit shows of fright,” Nadelberg writes in “The Moon Went Away,” but it is “[t]ime for all the what you want, darlings, / darlings, take the fear from your mouths / and listen, blow on the loveliest lamps.” And in the midst of these poems’ well-lit party are the traces of an excellent soundtrack, including references to Springsteen, Dylan, AC/DC, and Stevie Nicks, confirming that these poems aren’t willing to be so serious they forget the music, beyond poetry, that lifts and rescues us daily. From “Here in the Space-Time Continuum”:

I shine. I

keep trying. I mean, why not, I am out

of small slips of paper and if Stevie

Nicks can be broken-hearted then so can

I. I’m going to get red tights. No. No

no, I will sit right here. If I ever wear

lipstick I’d like it to be “June Bride.”

The reference to “June Bride,” a 1948 comedy staring Bette Davis and Robert Montgomery, (which includes such wonderful moments as Montgomery’s character, drunk on hard cider, saying “Man’s best friend is the apple” before falling face first into the snow) again points to a larger cultural and emotional frame of reference for these poems, one in which what’s funny often leads to what is most affecting.

Certainly, these poems are brave and exciting due to their freedom of feeling and association, but they also pop and show their intelligence when they elucidate their own meaning-making, presenting a kind of argument for reconsidering the experiential function of narrative, comparison, and understanding. “You could / be a narrative,” she writes in “This is When I Tell You Like It Is (Part Deux),” implying that a person or object, and here a pronoun, has the ability to contain a sequence of events simply, the poem seems to suggest, by existing in any emotional context. Furthermore, Nadelberg plays with the instability of simile and metaphor, acknowledging the transformations we can undercut and amplify in the cracks in language, as in “Dear Fruit” where she writes, “I am a terrible river but with you / I was a yellow shoe holding open a door. / Riding around in the park like a ship / the car was only itself.” Also, reinforcing Stein’s belief in the role of feeling in understanding, in “The Dinosaur Dreams Its Colors Into View” Nadelberg writes

Certainly, these poems are brave and exciting due to their freedom of feeling and association, but they also pop and show their intelligence when they elucidate their own meaning-making, presenting a kind of argument for reconsidering the experiential function of narrative, comparison, and understanding. “You could / be a narrative,” she writes in “This is When I Tell You Like It Is (Part Deux),” implying that a person or object, and here a pronoun, has the ability to contain a sequence of events simply, the poem seems to suggest, by existing in any emotional context. Furthermore, Nadelberg plays with the instability of simile and metaphor, acknowledging the transformations we can undercut and amplify in the cracks in language, as in “Dear Fruit” where she writes, “I am a terrible river but with you / I was a yellow shoe holding open a door. / Riding around in the park like a ship / the car was only itself.” Also, reinforcing Stein’s belief in the role of feeling in understanding, in “The Dinosaur Dreams Its Colors Into View” Nadelberg writes

A person has to

feel something to believe it.

If a person has a face

it could be very hard for

that person to imagine

having another face.

Does anyone understand

anything? Two benches

are two people. Words are

kinds of special to any

body.

Here, the plural “kinds” and break on “any / body” are what create all kinds of celebratory radiance. Bright Brave Phenomena is full of such moments, but never as cute tricks. These poems are honest emotional structures, admitting their weaknesses, asserting their joys, and embracing their obsessions. Through it all, as the book’s title suggests, these poems, inciting curiosity and out-of-the-ordinary interest, refuse to be artifacts of resignation. From “This All Came From a Box, Find a Bright Way Out”:

I don’t know how to gauge defeat.

There are still more chances,

little friends, the way wind

would form a thing. I decided

to become wonderful, found my

legs and removed a heart.

Good thing that Nadelberg’s poems remind us how many hearts we have, and how necessary it is to keep giving them away. Enjoy this book. It insists.

[Published April 24, 2012. 118 pages, $16.00 paper]

Nick Sturm is the author of WHAT A TREMENDOUS TIME WE’RE HAVING! (iO Books), as well as four other forthcoming chapbooks: A Basic Guide (Bateau), Beautiful Out (H_NGM_N), I Feel Yes (Forklift Ink), and, with Wendy Xu, I Was Not Even Born (Coconut). He lives in Tallahassee, Florida.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Anna Journey

Copperhead by Rachel Richardson (Carnegie Mellon University Press)

Asked whether or not I identify as a Southern poet, I often don’t know exactly what’s being asked of me. And when C.D. Wright observes in her poem, “Our Dust,” “I was the poet / of shadow work and towns with quarter-inch / phone books, of failed / roadside zoos,” one suspects she’s been asked that question regularly, too. Are we yarn-spinners in love with spells and sweet tea, people with sticky foods for nicknames? Do we sleep with Dickey tucked under our pillows? At times, folks ask The Inevitable Southern Question out of critical earnestness and, at other times, with an air of patronizing regionalism. While such labels may serve a practical purpose beneath a book’s ISBN, they are reductive in their failure to account for a collection’s complexities, surprises, and subtleties. Folks, a poet is more than her Spanish moss or muscadine jelly.

The work of Rachel Richardson, author of the debut poetry collection, Copperhead, may be vulnerable to the reductive potential of the Southern poet caricature. Richardson does in fact foreground many representations of “Southerness”: her portraits of Leadbelly and the young Britney Spears, section three’s epigraph from Mark Twain, imagery of swamps and parishes, a community fraught with racial tensions, family histories evoked with local color and quirky vernacular. Richardson subverts those poems that enact the dominant narratives of Southern representation, however, through her poems of fragment and mystery, which act as both interrogations of and glosses upon those dominant narratives. Furthermore, I’d argue that like the two definitions of the word “copperhead” in the book’s initial pair of epigraphs — the Northern traitor who sympathizes with Secessionists and the dreaded venomous snake — Richardson’s poetic vision in the collection is a plural one. The various sides act not as mirror images but as warped pairings that distort our more familiar perceptions of “Southerness” — foils that through nuanced narratives and discreet details keep us destabilized and thoroughly seduced.

The work of Rachel Richardson, author of the debut poetry collection, Copperhead, may be vulnerable to the reductive potential of the Southern poet caricature. Richardson does in fact foreground many representations of “Southerness”: her portraits of Leadbelly and the young Britney Spears, section three’s epigraph from Mark Twain, imagery of swamps and parishes, a community fraught with racial tensions, family histories evoked with local color and quirky vernacular. Richardson subverts those poems that enact the dominant narratives of Southern representation, however, through her poems of fragment and mystery, which act as both interrogations of and glosses upon those dominant narratives. Furthermore, I’d argue that like the two definitions of the word “copperhead” in the book’s initial pair of epigraphs — the Northern traitor who sympathizes with Secessionists and the dreaded venomous snake — Richardson’s poetic vision in the collection is a plural one. The various sides act not as mirror images but as warped pairings that distort our more familiar perceptions of “Southerness” — foils that through nuanced narratives and discreet details keep us destabilized and thoroughly seduced.

Throughout Copperhead, Richardson exhibits at least two markedly different subgenres of poems, which I’ll call — borrowing from the poet’s own language — “portraits” and “notes.” The “portraits,” which comprise the prevailing type of poem, strike me as conventional narratives that foreground either family history (grandmothers, sisters, a beloved family friend named Lola) or Southern history (executions, racial injustice, notorious figures). These poems build meaning through the logic of telling stories — or parts of them — and tend to strive toward closure and epiphany. The “notes,” the secondary type of poem, are fragmentary, short, elliptical, resist closure, and accrue meaning through associative logic through the rapid juxtaposition of images, often without explication or commentary. To characterize Richardson’s two main approaches to poems in such a manner is not to reach for easy or reductive labels, it’s to appreciate the sophistication and heterogeneity of her work.

Richardson’s series of seven elliptical lyrics — all titled “[sign]” and scattered throughout the book’s three sections — make up the bulk of the latter kind of poem I’ve described that ruptures the more conventional syntax, linear progression, and closure of the family/historical narratives with mystery, fragment, and a sense of unresolved or submerged danger. Here’s the first of these “notes” poems in the book:

( sweet tea / big girl / get up off your knees )

The lesson is: stop crying. Flies are drawn to honey, not

vinegar. This is how a girl gets what she wants. Beaucoups

dollars, shoes.

Sometimes a bridge goes over a river. Sometimes it goes

over a road.

Sign: Bible answers will be given to many Qs

The way Richardson utilizes both a secular folk saying (“Flies are drawn to honey, not / vinegar.”) and an eccentric Protestant quip (“Bible answers will be given to many Qs”) contrasts established modes of communal wisdom with “big girl”’s own internalized “lesson”: that she’ll get what she wants by ceasing her tears and acting sweet instead of sour. And one must admire the resourcefulness of the lyrical ear that brought together the mellifluous assonance and flavorful Cajun dialect in the sentence fragment, “Beaucoups /dollars, shoes.” I admire the energy and momentum of this poem, how its juxtapositions rapidly develop an interrogation into how we negotiate differing registers of wisdom in our lives. I also appreciate Richardson’s implicit critique of the Bible sign’s dubious offer, with her omission of the final sentence’s punctuation. Richardson’s sly defiance of the sign’s abstract proclamation seems more in step with the concrete stability of the bridges, despite the shifting unpredictability of the rivers or roads that may run beneath the structures.

The way Richardson utilizes both a secular folk saying (“Flies are drawn to honey, not / vinegar.”) and an eccentric Protestant quip (“Bible answers will be given to many Qs”) contrasts established modes of communal wisdom with “big girl”’s own internalized “lesson”: that she’ll get what she wants by ceasing her tears and acting sweet instead of sour. And one must admire the resourcefulness of the lyrical ear that brought together the mellifluous assonance and flavorful Cajun dialect in the sentence fragment, “Beaucoups /dollars, shoes.” I admire the energy and momentum of this poem, how its juxtapositions rapidly develop an interrogation into how we negotiate differing registers of wisdom in our lives. I also appreciate Richardson’s implicit critique of the Bible sign’s dubious offer, with her omission of the final sentence’s punctuation. Richardson’s sly defiance of the sign’s abstract proclamation seems more in step with the concrete stability of the bridges, despite the shifting unpredictability of the rivers or roads that may run beneath the structures.

One of the most striking poems of the “portrait” variety is the prose poem “The Scale” that weighs a series of halved or parallel images in a family narrative fraught with division and darkness. In the first two stanzas, Richardson writes:

The swamps and the silver coffee tray I loved with equal pas-

sion. And, too, finding a robin’s nest flung to the ground in

wind, with three of its eggs destroyed, and three babies bleating.

The world was nothing if not fair. Bread almost broke itself

into halves.

The asymmetrical pairing of the familiar swamp and the coffee tray, the three crushed eggs and the three live birds, and the “almost” perfectly self-halving loaf suggests that aspects of the speaker’s family circumstance will be revealed as similarly fractured or askew. Take, for example, the following stanza in which the speaker’s flâneur father wanders “block by block as / if to divide the city were to understand,” and how, in the fourth stanza, we find the speaker engaging — or perhaps refusing to engage — a malevolent elderly racist with divisive intent:

“What’s the difference between a live_____________and a

dead_____________?” a friend of my grandmother’s asked, el-

bow to my ribs, a secret grin poisoning his face. He had me

alone in the sitting room, among Chinese silk cushions.

A place for silence and a place for speech. Friend chicken is an

induction. Beer cans on the stoop.

The man’s “poisonous” joke, deliberately disarmed of its racial slurs in the poem by the author (“A place for silence and a place for speech”), recalls the juxtaposition of the live and the dead fauna in the first stanza. But even amid the creature comforts of “Chinese silk cushions,” friend chicken, and beer, the speaker is ill at ease in such offensive company and her preoccupation with division continues. The poem becomes increasingly stifling as Richardson evokes a scene claustrophobic with both kitsch and a peculiar, stylized gentility:

One evening at the Hobbit Shop, green in the night-lit

emptiness, she threw a party to introduce us to the neigh-

borhood girls. A stuffed lion moodily shadowed a train on a

circular track. The arms of porcelain dolls reached for finger

sandwiches on trays.

Like the toy train never arriving at its destination on a circular track or the gap between Adam’s finger and the hand of God on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Richardson’s porcelain dolls’ reach remains imperfect, divided from the object of desire. Elsewhere, at the end of “The Scale,” Richardson’s enactment of division is more explicit:

…one day, in anger, my sister threw me into

the Robinsons’ pool.

Because to divide is God’s will?

Underwater, I tried to pretend I had jumped on pur-

pose, crossing my legs in my billowing rose-print dress.

I raised an imaginary teacup to my lips, determined to

remain until someone fished me out.

By the end of Copperhead, I could contribute a general definition of what constitutes a Southern poet—a writer concerned with regional landscapes, Southern history, family narratives, racial tensions, Protestant ironies, vernacular wisdom, and the idiosyncrasies of a community that must find ways to honor and, at times, indict its own historical culpability—but that might be way too tidy. I’ll say, instead, that the way Richardson’s speaker in “The Scale” attempts to sip from an imaginary teacup after being shoved into the pool by her sister is perhaps a kind of uniquely stylized composure within extremity. One delights in the imaginative performance of her pride even as she hopes for salvation, a desire that, call it the “Southern spirit”—or not—we all may secretly harbor.

[Published February 17, 2011. 87 pages, $15.95 paperback]

Anna Journey is the author of two collections of poetry: Vulgar Remedies (Louisiana State University Press, 2013) and If Birds Gather Your Hair for Nesting (University of Georgia Press, 2009), selected by Thomas Lux for the National Poetry Series.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Rusty Morrison

To Keep Love Blurry by Craig Morgan Teicher (BOA Editions)

What can it mean To Keep Love Blurry — an infinitive phrase suggesting not only value but vigilance. In his second poetry collection, Craig Morgan Teicher demonstrates what is irreconcilable in our commonplace: “Ironic —or not? — that what shames you most is organically yourself?”; what is ineluctable in our tedious internal squabbles —“Well here we are. Does night / race or erase the time / between now and morning?” Such questions make apparent that neither alternative can be the simple answer. They wink conspiratorially toward a reader in tone, and replace any faith in incisive resolution with a hankering for what Giorgio Agamben has subversively extolled — that we should observe, even cultivate our “ways of not knowing.” Agamben is not promoting “carelessness” or “inattention,” but “an art of ignorance,” or as Teicher calls it “blurry”-ness. Agamben explains that “the articulation of a zone of nonknowledge is the condition — and at the same time the touchstone — of all our knowledge.” This zone is where Teicher’s “blur” takes us. Hear it in Teicher’s “Well here we are,” which registers the value of recognizing with humor and compassion the impossibilities that plague us. As Agamben has recommended, Teicher allows “an absence of knowledge to guide and accompany” him.

I hide beneath the sheets, close

to your belly, and apologize

—to you, to my mother, to our son,

to motherhood and fatherhood,

to all those now fleeing

what they love.

………………………..

You may not understand—I don’t

either—but someday we might:

Someday shines on families like light.

The “shine” of that “someday,” which ostensibly proposes a future understanding, actually underscores the value of this moment—its “light” is in the mutual acknowledgement of what can’t be parsed in the present with logical practices.

This collection takes as its purported subject the characters of Teicher’s life story, or let us call it his “Life Studies,” since the first section is so titled, with a bow to Robert Lowell. Indeed, we might take Teicher at his word when he offers humorously — “If Robert Frost is my mom, / then so is Robert Lowell.” And, yes, there is the pull toward the “bare sorrow” of Frost, as Randall Jarrell called it, which is set against what Teicher describes as the “charm” of Lowell’s “show” of “self loathing.” In addition to his articulated allegiances to Lowell and Frost, Teicher acclaims the value of W.G. Sebald’s “detachment,” — “What more could a mourner want than the cool capacity to simply watch without longing?” Though this is another question that has no simple answer, thanks to Teicher’s deft ability to resist, even in his praise, an unequivocal stance. Hear it in his appreciation of Sebald’s ability to “think until feelings are only thoughts and so less potent, less capable of surprise, whether as rapture or despair.”

This collection takes as its purported subject the characters of Teicher’s life story, or let us call it his “Life Studies,” since the first section is so titled, with a bow to Robert Lowell. Indeed, we might take Teicher at his word when he offers humorously — “If Robert Frost is my mom, / then so is Robert Lowell.” And, yes, there is the pull toward the “bare sorrow” of Frost, as Randall Jarrell called it, which is set against what Teicher describes as the “charm” of Lowell’s “show” of “self loathing.” In addition to his articulated allegiances to Lowell and Frost, Teicher acclaims the value of W.G. Sebald’s “detachment,” — “What more could a mourner want than the cool capacity to simply watch without longing?” Though this is another question that has no simple answer, thanks to Teicher’s deft ability to resist, even in his praise, an unequivocal stance. Hear it in his appreciation of Sebald’s ability to “think until feelings are only thoughts and so less potent, less capable of surprise, whether as rapture or despair.”

Obviously, wise elders abound in this collection, but none will quite account for Teicher’s vigilant candor in the ways that he vitally enacts the “blurry.” Even in a collection that is rich with the past’s re-enactment, he admits that the most relevant memories, the most clarifying instances of forgotten dream, are most likely irretrievable, “locked away somewhere.” Surprisingly, Teicher lets us feel the ways in which such a memory’s very irretrievability will offer him something more valuable than clarity: “When I realize I am waiting for it, I feel childhood rising within me: powerlessness, hope.” No writer I know exposes better Giorgio Agamben’s dictum, that “[t]he ways in which we do not know things are just as important (and perhaps more important) as the ways in which we know them.”

Or as Teicher elaborates, turning a question of meaning inside-out in response to his son’s inscrutability:

What’s to be gleaned from what a child

does and why? He’s simply not given to

interpretation, mine or his own. That’s

the lesson: some things aren’t anything

else. Then, later, all things are other things …

That “some things aren’t anything” (are simply unimportant) shape-shifts in its meaning at the enjambment into “some things aren’t anything else” (which can mean they are entirely without equivalent, even semantically, and that they are simply what they seem to be), and leads, “later,” to “all things are other things” (which suggests that meaning is never what you expect). Teicher is gifted in his plainspoken articulations of a world steeped in disequilibrium for the child and parent alike. But disequilibrium does not engender despair. Teicher’s many vertiginous shifts do not leave us in a landscape of ennui, though a summary of the book’s subjects might suggest this — the loss of his mother while still a child, the fear of failed artistic accomplishment, the often inscrutable responsibilities of fatherhood and marriage. But such fierce challenges, such exacting portrayals of suffering, remain infectiously subversive of sorrow. Even the epigraph hints at this: “For Cal and Simone [his children] — you should know that it’s a lot more fun that these poems suggest — and for Brenda, who knows …”

That “some things aren’t anything” (are simply unimportant) shape-shifts in its meaning at the enjambment into “some things aren’t anything else” (which can mean they are entirely without equivalent, even semantically, and that they are simply what they seem to be), and leads, “later,” to “all things are other things” (which suggests that meaning is never what you expect). Teicher is gifted in his plainspoken articulations of a world steeped in disequilibrium for the child and parent alike. But disequilibrium does not engender despair. Teicher’s many vertiginous shifts do not leave us in a landscape of ennui, though a summary of the book’s subjects might suggest this — the loss of his mother while still a child, the fear of failed artistic accomplishment, the often inscrutable responsibilities of fatherhood and marriage. But such fierce challenges, such exacting portrayals of suffering, remain infectiously subversive of sorrow. Even the epigraph hints at this: “For Cal and Simone [his children] — you should know that it’s a lot more fun that these poems suggest — and for Brenda, who knows …”

Watching Teicher in the act of keeping vigil to life’s blurriness is — dare I say it — “a lot more fun” for the reader as well. Take for example even a poem in which the phrase “all words stand for pain” is repeated twice: “To An Editor Who Said I Repeat Myself and Tell Too Much.” Here, the repetition manages to both underline the phrase’s meaning and displace it — becoming as much a rebellious rebuff of the editor by repeating the criticized offence as it is lament. So many of these poems suggest that any experience cannot be understood at surface value, which keeps somberness as questionable as any other pose, especially when it is paired with the sensuous physicality of Teicher’s humor:

the mouth works all its life to spit a vowel—

some long sound with feeling fenced in

by the sharp stops of a few consonants, a howl

In many poems, Teicher uses the structural certainties of repetition and rhyme, which recall childhood lyrics and lullabies, recreating a seemingly trustworthy frame for the dis-clarity and disruptiveness of experience. In this way, Teicher’s casts a quiet enchantment upon suffering — a lilting air of mystery holds sway. As Amittai F. Aviram explains, a poem rich in repetition, rhythm, rhyme, “retains a residue of the … meaningless or nonreferential” as the reader “feel[s] the tension between … these two dimensions in the poem, the meaningful and the meaningless.”

Notably, the book’s first poem engages in rhythmic repetition to introduce a character of fairytale mystery and paradox, suggesting immediately that we must read Teicher with our eyes open to what simple logic can’t disclose to us. “In the land of rivers I was a prince of rivers… / In the land of questions I was the subject of questions. / I’m sorry what was lost was utterly changed …” Think of Robert Walser’s protagonists, whom J.M. Coetzee calls “fairy-tale characters once the tale has come to an end.” Yet Teicher is uncannily adept at exposing even the painful ‘reality’ of surfacing-at-the-end-of-the-fairytale as simply another ineffective realization of the actual, another experience to watch closely, to see where it “blur[s].” Read Teicher to understand why Agamben says “The art of living is, in this sense, the capacity to keep ourselves in harmonious relationship with that which escapes us.”

[Published August 21, 2012. 110 pages, $16.00 paper]

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Hank Lazer

If by Leonard Schwartz (Talisman House)

Leonard Schwartz’s If is, as advertised (in Rebecca Brown’s blurb), “a profound and moving book, a modern book of wisdom that merits rereading again and again and again.” If may in fact be Schwartz’s finest book. What interests me most about this book, though, is what I think of as the metric of wisdom, or perhaps more accurately, the metric of dispensing wisdom. Schwartz has an eloquence – a seeming ease of writing – that carries If along. He has a facility for a kind of grand statement with a touch of humor and irony that reminds me of Ashbery. As with Ashbery, I end up wondering about the function, value, and nature of that eloquence.

And yet, a major strand of If is the opposite of a proud eloquence; the overall book, in its beautifully stately couplets, speaks as much to aging, diminished accomplishment, and a humbling relationship to time:

Now I think it is my turn to miss the point

Yet a voice has many arms and builds us a life

Even after language is pillaged of its magic

And flowers no longer know our individual names

Foothills continue to give meter to the way we speak

And glaciers give it weight, thrown boulders

Suggestive of the force of things, so violent

So fragile and so forlorn that by comparison

You can fit any one of our endeavors

Into a little pocket on an ice cube tray.

Even this brief passage provides a good sense as to the seemingly effortless flow of generalization that Schwartz is able to achieve, and the passage also typifies a turning back on itself by questioning or contextualizing the poetic performance itself. Threats of illness and mortality keep the somewhat manic eloquent performance in check: “How avoid betraying / The necessary elegy?”, and, in reference to the poet’s daughter’s illness, “I love her too much to any longer / Distance myself from disease.” Or, the peril implied in these lines: “As if roped together like mountaineers / Parent and child begin the day’s difficult ascent.”

Even this brief passage provides a good sense as to the seemingly effortless flow of generalization that Schwartz is able to achieve, and the passage also typifies a turning back on itself by questioning or contextualizing the poetic performance itself. Threats of illness and mortality keep the somewhat manic eloquent performance in check: “How avoid betraying / The necessary elegy?”, and, in reference to the poet’s daughter’s illness, “I love her too much to any longer / Distance myself from disease.” Or, the peril implied in these lines: “As if roped together like mountaineers / Parent and child begin the day’s difficult ascent.”

In person and in poems, Schwartz is funny, quick, and sharp in his observations, as in this snapshot of the contemporary:

So everyone texts everyone else

As if this were a silent movie

And the viewer has to wait for the words to appear

As to make sense of the preceding image.

It takes an extended passage to convey the quality of performance involved in Schwartz’s long poem – the way that the poet builds thought upon thought on the scaffolding of the recurring “if”:

If one rarely leaves the cloister of

The Mother Tongue even when ushered

By the conversation elsewhere, if some

Borough of the broken is inescapably one’s voice

If possibilities come into being and pass away

As actualities do, though they never really were

If a bulldozer lurks in every

Innovation

And the alphabet remains essentially unchanged

For thousands of years

If the warming flesh of rhetoric is

Cut away and the spiritual

Bone-structure underneath

Is, surprise, neither warm nor fleshy

If under the pressure of the tragic

Speech seeks out the clearly other

If my mind disengages the moment we start

Imperiously diagnosing our societal ills

If what is said

Is what is sad

If we are signs without interpretation

And what is contemporary in me

Is the sun, the moon, and the stars

Our existence at an inner distance

This community of persons

Born in the same instant

And each instant precious in which cars

Of a moving train do not decouple.

Schwartz’s performance is admirable, and the virtues and problems of this mode of writing are similar to those for Ashbery’s work. As Schwartz himself notes, “If I’m a raincloud and can’t stop talking/ We all get drenched.” There is simultaneously a glorious, inspiring quality to the beauty of the writing along with a sense of it being a masterful performance that, at times, loses sight of the poet’s plausible relationship to the truths and wisdom at the heart of the poem. It’s as if the poem proceeds on autopilot, obeying its governing if-structure, and displaying an engaging inventiveness that perhaps allows us to return to (or wait for) the more centrally profound moments of wisdom. Perhaps If is a transitional work for Schwartz, one where he begins the process of weaning himself from an accomplished eloquence to engage other possibilities: “The loss of impetuousness unfolding over / A thirty year period as if in a few minutes // Contributes to my decision / To lay aside my counterfeiting activities // Even if that means / I can no longer fool my peers.”

Schwartz’s performance is admirable, and the virtues and problems of this mode of writing are similar to those for Ashbery’s work. As Schwartz himself notes, “If I’m a raincloud and can’t stop talking/ We all get drenched.” There is simultaneously a glorious, inspiring quality to the beauty of the writing along with a sense of it being a masterful performance that, at times, loses sight of the poet’s plausible relationship to the truths and wisdom at the heart of the poem. It’s as if the poem proceeds on autopilot, obeying its governing if-structure, and displaying an engaging inventiveness that perhaps allows us to return to (or wait for) the more centrally profound moments of wisdom. Perhaps If is a transitional work for Schwartz, one where he begins the process of weaning himself from an accomplished eloquence to engage other possibilities: “The loss of impetuousness unfolding over / A thirty year period as if in a few minutes // Contributes to my decision / To lay aside my counterfeiting activities // Even if that means / I can no longer fool my peers.”

So am I really asking that the poem have a higher percentage of passages of less eloquent, less performative, less comedic or ironized “wisdom”? It might also be argued that in fact such a debate is already within the domain of If, a poem deeply committed to wondering how a poet, how Schwartz, might ever say what is true – “If the aspect of language that melts away/ Is the part that tells the truth.” Or perhaps the truth of If lies in the acknowledgment of dissolution as the inevitable condition of any extended language performance (which might also be another way to describe a human life?):

If it is so clear earthly life is corrupted by time

That the concept of “corruption” itself decays

And is discarded, leaving us only with time,

Time and the collective memory of earthly time;

If memory is the only victory over time

But the concept of “victory” loses all its pluck:

The comic models freedom and elasticity

And whatever dissolves whenever approached.

Admittedly, it would take another essay to explore the specific nature of Schwartz’s own comedic methodology – quite different, say, than Charles Bernstein’s mode of the comedic (based on a transformation of stand-up comedy) – but let me suggest that If points toward a more encompassing metaphysical point of view, something akin to Kenneth Burke’s (ethical and philosophical sense of) a comic frame of acceptance. That comic frame of acceptance comes from a tragic sense of our existence, a perspective that Schwartz pushes even further (so that we might see ourselves possibly as the bearer of death):

If we are a living speck surrounded by death

On a planet that supports life some of the time

On some of its surface, icy

Or burning or dry, or if we are the germ of death

Spreading itself amongst a mass of living cells

And forces succumbing around us as we grow …

Perhaps all that we can do is to extemporize – to perform the mixed eloquence of If as a heuristic process of knowing by doing:

One cannot prepare in advance

For one’s conversation with unknowns

And so there’s no reason to stop

Making it all up on the spot.

If it isn’t extemporized it isn’t the important

Conversation… never write about what one knows.

Sacrilege! “We do what we know

Before we know what we do” (Creeley)

So that where we find ourselves – and If is definitely the testing-by-writing-it of shifting perspectives on who and what we are – is in a place simultaneously of beauty and constraint:

A treasure impossible to describe,

Subduing even those not consciously aware.

If sacrifices are required there is

No god or mortal who would not offer himself.

If speech is the source of a compensatory

Cosmos in the mouth

If the unknown can only be created

Out of what is known

And the known is already created stuff

A cow fence electric with current

Please set me free from anguish as one might

A calf from a rope, a horse from a bit.

For our circumstance, in human being, and in our loving relations with other mortals, is one of anguish. A poem, then, a poem such as If, becomes a way to share perspective, to make a vision and saying trans-personal, though with the awareness, as beings in time and as beings constrained by our own radical particularity, that we will, to a great extent, miss one another:

If an individual’s thinking is a mystical ground

Between concealment and disclosure

If a private point of view

Both particularizes and traps

Like a sharp knife plunging

Into the chatter of good intentions –

Suppose each of us our own time zone

Such that by the time one reaches the other

One is already jet-lagged.

But with effort, with some rest, we can shake off the jet-lag and join one another in this time, in the place of speculation and eloquence that pours forth from that profoundly initiating and simple word if.

[Published October 20, 2012. 88 pages, $15.95 paper]

Hank Lazer has published seventeen books of poetry, including Portions, The New Spirit, and Days. His seventeenth book of poetry, N18 (complete), a handwritten book, is available from Singing Horse Press. Lazer’s most recent collection of essays is Lyric & Spirit (Omindawn, 2008).

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Lisa Russ Spaar

Nine Acres by Nathaniel Perry (The American Poetry Review)

All poetry, whether free verse or no, is formal. And all poems, whatever their ostensible subjects, are finally also about form: the torsos of language they erect, the fields of white space their lines plough, and in which their words alight and from which they take flight. Nathaniel Perry’s Nine Acres, winner of the American Poetry Review/ Honickman Book Prize, takes its 52 poem titles from the 52 chapter headings of a go-to farm manual, Five Acres and Independence, written by M. G. Kains and published in 1935. Perry’s is a daringly formal book.

All poetry, whether free verse or no, is formal. And all poems, whatever their ostensible subjects, are finally also about form: the torsos of language they erect, the fields of white space their lines plough, and in which their words alight and from which they take flight. Nathaniel Perry’s Nine Acres, winner of the American Poetry Review/ Honickman Book Prize, takes its 52 poem titles from the 52 chapter headings of a go-to farm manual, Five Acres and Independence, written by M. G. Kains and published in 1935. Perry’s is a daringly formal book.

Each poem (with Kains-borrowed titles like “Essential Factors of Production,” “Green Manures and Cover Crops,” “Who is Likely to Succeed?,” and “Figures Don’t Lie”) consists of four tetrameter quatrains, often enmeshed by rhyme schemes. In the overarching story of the series, the speaker narrates his young family’s acquisition of and engagements over time with nine acres of rural property. But the poems themselves — as agile, nimble, sexy, smart, and culturally and linguistically savvy as his prosody is regular — are about much more than agricultural husbandry. Eschewing any over-simplification of this endeavor, or of the heart, even as they strive for an utter clarity of expression, these are love poems —f or place, for spouse, for children, for the making and the mystery of making. Here is “Soils and their Care”:

The field we bought is filled with clover.

You are still my lover, I am still

yours. Our children are halfway here,

and we try to imagine being filled

more—like a pint of beer before

it loaves above the glass and kisses

the landlord’s hand. Remember the year

we lived in London? We don’t miss

it much, but you were my lover there

as well, and I was yours, which was

a good way to be in the city, so many

roads to cross and places to puzzle

over. And what, exactly, binds

this August meadow and that year?

I could say love—we’d all, of course,

expect that. I should, but won’t, say fear.

What is it — if not love, fear, beauty, and desire — that leads us to create things: a garden, an orchard, a family, a poem? As I suggested above, Perry’s poems are, in essence, about this impulse to transform a field, to form a poem, to be formed by the act of making. Poems like “Who is Likely to Succeed?” have as foreground and subtext a meta concern with their own cultivation, shape, and process:

What is it — if not love, fear, beauty, and desire — that leads us to create things: a garden, an orchard, a family, a poem? As I suggested above, Perry’s poems are, in essence, about this impulse to transform a field, to form a poem, to be formed by the act of making. Poems like “Who is Likely to Succeed?” have as foreground and subtext a meta concern with their own cultivation, shape, and process:

I always assumed beginnings were

the best places to start. But times

are that middles are all you see

or something slowly muddles the line

between starts and middles or middles and ends,

like love, or something just like love

but more so for its having lit

the corners of what you’d always thought of

as the start of something but now

seems exactly like the middle

of something else, a thing you had thought

you might miss, like the sweet note on a fiddle,

if you’d tried. And now my song’s all soured

with thinking. I’ll start over. It begins:

you, then you, then here, where the trees

are bright, will soften, will brighten again.

Farm. Form. Coincidence? Form, Perry writes in “Introduction,” is “that which hunts before me, / that which is not dark in the darkness.” In his farming manual, M. G. Kains writes that above all, farm life “gives the thinking observer mastery over his business, brings him en rapport with his environment and in tune with The Infinite.” Perry’s “The Farm Library,” in which Perry’s speaker directly addresses Kains’s text, ends this way:

What did Kains, his skiff

of a book shored up, his harvest stored

for winter, need me to know of knowledge?

That in seed and land we find an anchor,

and in language we weigh out our courage.

This figurative nexus of the wild order of horticulture is at the ardent heart of this collection.

[Published October 25, 2011. 96 pages, $14.00 paper]

Lisa Russ Spaar’s sixth collection of poems, Vanitas, Rough, has just been published by Persea Books. In March 2013, Drunken Boat media will publish The Hide-and-Seek Muse, a selection of her essays that had been published weekly from 2010 to 2012 for the Chronicle of Higher Education’s “Arts and Academe” blog. She teaches creative writing at the University of Virginia.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Christopher Merrill

Mara’s Shade by Anastassis Vistonitis, translated from the Greek by David Connolly (Tebot Bach)

Anastassis Vistonitis occupies a unique position in Greek letters: equally acclaimed as a poet and a journalist, he switches from one medium to the other with seeming ease, now composing poems and literary essays, now turning out book reviews and articles, often on the same day. Both streams feed the sea of his imagination—he calls his prose a continuation of poetry by other means — and his Greek readers are fortunate to have his work available to them in so many forms. He has published eleven collections of poetry, three volumes of essays, four travelogues, a book of stories, and a translation of the Chinese poet Li Ho; he edits and writes for the book section of To Vima, the leading newspaper; he even assembled the candidature file for the Athens Olympics, articulating the argument that convinced the International Olympic Committee to return the Games to their original site. Indeed his work is a testament to the ancient Greek idea of the intimate connection between the body and the soul. What good luck to have a selection of his poems in English, in the splendid translation of David Connolly.

Vistonitis cuts a large figure, both in his presence and on the page. He was born in 1952 in Komotini, near the Turkish border, and when an injury cut short a promising soccer career he threw himself into poetry, coming of age during the military dictatorship (1967-1974). His early work is marked by the artistic, intellectual, and political ferment of the time, and it is no accident that in his subsequent writings he exhibits a deep understanding of the relationship between literature and politics (he studied political science and economics in Athens); also a grasp of the world beyond Greece. He traveled extensively in Europe, Africa, and Asia, lived in New York and Chicago, where he perfected his English, and schooled himself in several literary traditions, ever mindful of the ethical dimension of his craft. His work is dense with allusion and insight, as befits one of the best-read writers of the age, and in these poems he displays not only a range of theme but also formal possibilities, from variations on Byzantine prosody to prose poems to lyrical meditations. Readers will instantly recognize the voice of a major poet.

Vistonitis cuts a large figure, both in his presence and on the page. He was born in 1952 in Komotini, near the Turkish border, and when an injury cut short a promising soccer career he threw himself into poetry, coming of age during the military dictatorship (1967-1974). His early work is marked by the artistic, intellectual, and political ferment of the time, and it is no accident that in his subsequent writings he exhibits a deep understanding of the relationship between literature and politics (he studied political science and economics in Athens); also a grasp of the world beyond Greece. He traveled extensively in Europe, Africa, and Asia, lived in New York and Chicago, where he perfected his English, and schooled himself in several literary traditions, ever mindful of the ethical dimension of his craft. His work is dense with allusion and insight, as befits one of the best-read writers of the age, and in these poems he displays not only a range of theme but also formal possibilities, from variations on Byzantine prosody to prose poems to lyrical meditations. Readers will instantly recognize the voice of a major poet.

“From the Side of the Sea,” for example, opens with a series of apocalyptic versets:

It was night when we descended the narrow path to the sea. No wind was blowing just as yesterday. Lights were mirrored in a black glass. In it we saw our faces’ negatives.

Far off appeared the flickers of a huge fire.

This is where we’ll stay till morning, I said, and the others didn’t speak. Another land began where the fire was fading and no one knew it. no one knew if what was burning was the great palace, as the day’s rumors had it, or gleams of a glory burning in time. Someone suggested we go to find the ash remaining before the wind scattered it.

Always there’s a sea intervening, said one of the others, with his voice covering his face. We, too, could find a fire and burn the sea. Glass doesn’t burn and what you see is not the sea.

The speaker, who claims to have born with a glass eye, goes on to raise questions —“Who is the night, what is the night, left right, O left right”— and pose hypothetical solutions: “If I were to jump, I’d find myself at the other edge of the sky, if I turned around. If…” He means to discover his bearings in a place that has not been mapped before and a time that demands a more accurate form of measurement than conventional literary practice offers. The situation is dire, and yet the very surge of these lines suggests that an imaginative response is possible—which, if nothing else, may make our walk in the sun more bearable. The poem thus concludes with an image —“The ruins of the fire in the palace began to set”— that in its seeming finality promises nevertheless that another sun will rise, another occasion to light the darkness.

The speaker, who claims to have born with a glass eye, goes on to raise questions —“Who is the night, what is the night, left right, O left right”— and pose hypothetical solutions: “If I were to jump, I’d find myself at the other edge of the sky, if I turned around. If…” He means to discover his bearings in a place that has not been mapped before and a time that demands a more accurate form of measurement than conventional literary practice offers. The situation is dire, and yet the very surge of these lines suggests that an imaginative response is possible—which, if nothing else, may make our walk in the sun more bearable. The poem thus concludes with an image —“The ruins of the fire in the palace began to set”— that in its seeming finality promises nevertheless that another sun will rise, another occasion to light the darkness.

This is what distinguishes Vistonitis: his determination to grasp the meaning of the fact, as he writes in a poem titled “1968,” that he is but “a fragment of all that [he has] encountered.” Whether exploring China, traveling on a train from Lisbon to St. Petersburg in the company of a hundred poets and writers, or reflecting on the achievement of literary figures from around the globe, he brings to bear an exacting and exuberant intelligence. “Nightmarish imagination,” he proclaims in the last line of this book: “you are not yourself, you are not, you are not.” Indeed it is other, it is the language itself, and in these poems it speaks for all of us, lighting the way.

[Published May 25, 2011. 116 pages, $15.00. To learn more about or contact the press, click here.]

Christopher Merrill is the Director of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Recommended by Shane McCrae

Fowling Piece by Heidy Steidlmayer (Triquarterly)

The title poem of Heidy Steidlmayer’s first collection, Fowling Piece, terrifies me. Here’s the whole thing:

FOWLING PIECE

The pull of guns I understand,

my father taught me hand on hand

how death is. Life asserts.

(Best take it like a man.)

I shot a dove, the common sort

and mourned not life but life so short

that gazed from death as if unhurt.

And I had nothing to report.

It’s the last line that scares me — that actually, really terrifies me. And Steidlmayer sets the reader up to be terrified with great craft: The poem moves smoothly to its conclusion, and distracts the reader along the way with a few straightforward, even bland, poetical remarks — the first three lines of the second stanza, especially, demonstrate Steidlmayer’s skill. The language is, again, poetical — a little lofty, a little stilted. It is the sound of a poet making an observation from a great height, but the observation itself is nothing more than that — the sound of a poet making an observation from a great height: “mourned not life but life so short.” This language is deployed to make the reader comfortable, to prepare the reader for a great and wise summing-up — and then, nothingness. An abyss opens up. The poet has contemplated death—more, the poet has made death happen — but whatever effect that had on her, if any, she isn’t sharing (sure, she says she “mourned,” but I don’t think that word is meant to communicate any real sadness or regret; I think it functions only as poetry, as a poetical sound). And the reader must confront, suddenly, the possibility that the killing meant nothing to the poet, that it affected her not at all. But how familiar the language! Up until that last moment, the poem reads so familiarly that it’s almost as if the reader has read it before, it’s almost as if the poem is already part of the reader. And so the last line strikes the reader as a moment of self-revelation, but it’s more the reader’s self than the poet’s that seems revealed. And I’m frightened by what seems revealed, even though it doesn’t correspond to what I know to be true about myself, precisely because it doesn’t correspond to what I know to be true about myself.

It’s the last line that scares me — that actually, really terrifies me. And Steidlmayer sets the reader up to be terrified with great craft: The poem moves smoothly to its conclusion, and distracts the reader along the way with a few straightforward, even bland, poetical remarks — the first three lines of the second stanza, especially, demonstrate Steidlmayer’s skill. The language is, again, poetical — a little lofty, a little stilted. It is the sound of a poet making an observation from a great height, but the observation itself is nothing more than that — the sound of a poet making an observation from a great height: “mourned not life but life so short.” This language is deployed to make the reader comfortable, to prepare the reader for a great and wise summing-up — and then, nothingness. An abyss opens up. The poet has contemplated death—more, the poet has made death happen — but whatever effect that had on her, if any, she isn’t sharing (sure, she says she “mourned,” but I don’t think that word is meant to communicate any real sadness or regret; I think it functions only as poetry, as a poetical sound). And the reader must confront, suddenly, the possibility that the killing meant nothing to the poet, that it affected her not at all. But how familiar the language! Up until that last moment, the poem reads so familiarly that it’s almost as if the reader has read it before, it’s almost as if the poem is already part of the reader. And so the last line strikes the reader as a moment of self-revelation, but it’s more the reader’s self than the poet’s that seems revealed. And I’m frightened by what seems revealed, even though it doesn’t correspond to what I know to be true about myself, precisely because it doesn’t correspond to what I know to be true about myself.