Woody Haut on Writing On Dangerous Ground

What Is Noir?

Is more than darkness. Is

corruption of the heart. Is

behind closed doors, board-

room or street. Is fucked

whether you do, don’t sing,

moan, sniff or shoot. Is a

ticket to all we have, never

enough. Is greed, lust, a fatal

kiss, the banker, cop, criminal, or

any other poor sucker who

screams for mercy. Is a

dream of autonomy, femme

fatality causality, breathing,

“Hey, baby, let’s take it all.”

is a corpse, a handful of dust

and ultimately who cares, if

the only punishment is death.

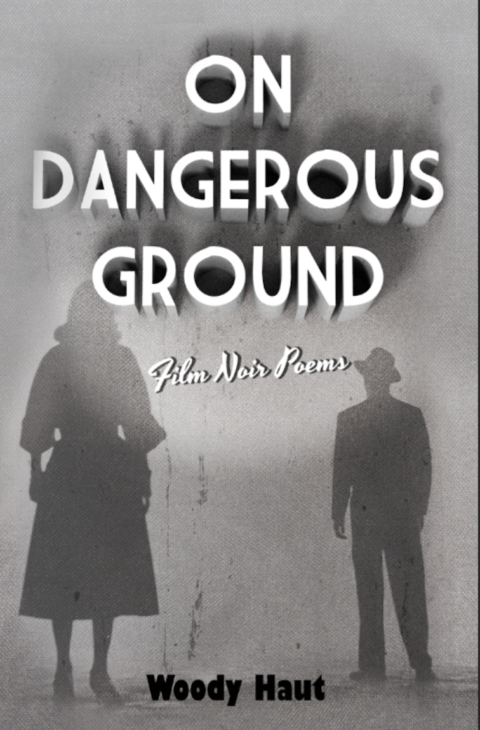

On Dangerous Ground, a book I began writing in 2012, comprises 50 poems based on classic examples of film noir. I wanted each poem to be accompanied by an image from the film under consideration. My initial intention was to write solely about the images, what they contained and implied. But soon, shifting from that remit, I deployed the images more as starting points, allowing me to move outwards, into the world surrounding those images — a kind of memory theater, setting off thoughts, reactions, rants and investigations. A tangential process that peered at aspects of the films themselves: dialogue, lighting, set designs, and the roles of directors, screenwriters, cinematographers and producers.

As I rewatched the films, I began to view them more as artifacts requiring response rather than commodities existing in a static environment. This meant the films activated the poems, and the poems reanimated the films. It also allowed me to address subjects such as crime, guilt, innocence, bourgeois values, late capitalism, and gendered space.

I had spent 30 years in the trenches of noir fiction and film – so why suddenly turn to poetry as the genre for my investigation? Poetry had been my first port of call, though over the years my relationship had succumbed to disgruntlements and separations. Blame it on the term “poet” and the bad faith it often entails, or absolutist dictums such as Pound’s about poets being the antennae of the race (about which one can only ask, what race might the great poet have been referring to?). Even so, my relationship with poetry was never to devolve into a divorce. I still carry the baggage, if not the scars, stretching back to the mid-1960s, in Los Angeles, then San Francisco, with various publications and a range of mentors, from the academic — Henri Coulette, Philip Levine, Jack Gilbert — to the peripatetic — Michael McClure, Charles Olson, Amiri Baraka and Ed Dorn. More recently, my interest veered towards the more linguistically-oriented, such as Clark Coolidge, Michael Gizzi, and Tom Raworth, and political screeds by the likes of Sean Bonney and Keston Sutherland.

I had spent 30 years in the trenches of noir fiction and film – so why suddenly turn to poetry as the genre for my investigation? Poetry had been my first port of call, though over the years my relationship had succumbed to disgruntlements and separations. Blame it on the term “poet” and the bad faith it often entails, or absolutist dictums such as Pound’s about poets being the antennae of the race (about which one can only ask, what race might the great poet have been referring to?). Even so, my relationship with poetry was never to devolve into a divorce. I still carry the baggage, if not the scars, stretching back to the mid-1960s, in Los Angeles, then San Francisco, with various publications and a range of mentors, from the academic — Henri Coulette, Philip Levine, Jack Gilbert — to the peripatetic — Michael McClure, Charles Olson, Amiri Baraka and Ed Dorn. More recently, my interest veered towards the more linguistically-oriented, such as Clark Coolidge, Michael Gizzi, and Tom Raworth, and political screeds by the likes of Sean Bonney and Keston Sutherland.

By negotiating the thin line separating romanticism from fatalism, film noir may be regarded as poetic as much as stylized. One need look no further than films like Robert Wise’s The Set Up (1949) and Nicholas Ray’s Party Girl (1958), both of which were originally rhymed narrative poems by Joseph Moncure March. Or consider Abraham Polonsky’s Force of Evil (1948), whose screenplay was written in blank verse. It could even be said that poetry and film noir both often rely on set formats, manipulate narrative coherency, and proceed by implication. As for the doomed film noir protagonist, it is not unusual for him, and it is usually him, to have the temperament of a thwarted poet, from the sadistic cop Jim Wilson (Robert Ryan) in Nicholas Ray’s On Dangerous Ground (1952) to the soda shop gangster Shubunka (Barry Sullivan) in Gordon Wiles’s The Gangster (1947). Slavoj Zizek, in his 1990s essay “From Courtly Love to The Crying Game,” insists that film noir’s proverbial femme fatale may be traced back to the Troubadour poets and their objects of obsession, though few of the latter could have been as deadly as Kathy (Jane Greer) in Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past (1947) or Margot Shelby (Jean Gillie) in Jack Bernhard’s Decoy (1946).

There are several poets who’ve established a working relationship with such films — Alice Notley, Robert Polito, Geoffrey O’Brien, Nicholas Christopher, and earlier, Weldon Keyes and Kenneth Fearing. Even Raymond Chandler began his writing career composing doggerel for the Westminster Gazette, while the great Dorothy B. Hughes garnered the Yale Younger Poets Prize long before she wrote such classics as In a Lonely Place or Ride the Pink Horse.

Why title it On Dangerous Ground? Besides it being one of my favourite movies, film noir, from the end of WWII to the end of the 1950s, really did find itself, cognisant or not, trespassing onto dangerous ground. So many of those films questioned the values of the era, from consumerism to the paranoia regarding the cold war and the bomb to fear of women in post-war society. Created in large part by leftists (Nicholas Ray, Jules Dassin), soon-to-be blacklisted writers and directors (Joseph Losey, Abe Biberman, Dalton Trumbo, John Berry) and European exiles, influenced by German Expressionism (Jacques Tourneur, Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak), the movies might have been screened in black and white, but the world they depicted was anything but. At least not in the hands of such cinematographers as John Alton, Burnett Guffey and Nicholas Muscuraca; or screenwriters like AI Bezzerides, Daniel Fuchs and Ben Hecht. But this was back when film noir had license to embrace its rough edges and romantic notions regarding the criminal, the cop, the private eye, the musician, the psychopath, the patsy, the autonomous woman, and other such subjects, a genre not yet categorised, commodified and eventually stripped of its populist concerns and politics.

— Woody Haut

/ / / / /

Woman On the Run (Norman Foster, 1950)

Who finds Playland sinister necessarily gumshoes

fate, not unlike Pinocchio ogling the Fat Lady before

dodging phallic double-parkers, bumper stickers

decrying the benefits of spousal abuse. Payback hot

wire exhaust fumes stodgily mashing suburban mush.

They said it was over even before it was over, the song

celebrating insinuation, or, better yet, the benefits of

capitalist degeneration. Those westward petit-bourgeois

wankers, ensconced in ocean-side condominiums,

wallowing in cryptic crossword clues and anxious

evenings of cathode narcolepsy. Gawked while stuffing

coupons into letterbox conspiracies. Others say only

movies make it real, concentrating the mind on guilt

rather than gelt. Leaving idle hands and loose ends to

track some alienated dog walker, thrust into the numinous

night. Witnessing shock and awe gangland murder not

far from where Kid Schlemiel once shared a joint with

Janis Joplin, who, for all I know, was in fact Daffy Duck

in disguise. Or is that stating the obvious? One person’s

truth being another’s collective amnesia. But, yes, the man

on the leash, marriage on the rocks, would have been

better off had he allowed his mutt to simply crap on

the carpet. Yet any deliberation over whose tail is wagging

what dog can only be speculative. That mask of civility

frozen at the seams, Mrs Dog Walker totes the medicine

that might alleviate her husband’s frozen heart. But loyalty

only goes so far; it’s not that she wants him dead, just out

of the way. Even if the guy she confides in is not now,

nor ever has been, a confirmed newshound. Still, he speaks

in complete sentences and treats her as if she just might

actually qualify as human. But tattoo this: never fully

trust a man in a film, circa 1950, who purports to take

a woman seriously. As for Foster, his bona fides are

themselves slightly suspicious, from the Mercury Players

to Mr Moto and Charlie Chan. Schlepped his puny budget

from L.A. to San Francisco to hoover the city’s crevices

Call it psycho-geography, but only if emphasising the prefix

of that neologism. As if the gaffer might have been stealing

glances at Schlemiel’s tear-stained Baedeker, to give him

license to prowl the city like a wounded coyote woofing

and warping at every pit stop. Either smart before its time

or retrograde after the fact, its laws and stipulations bleed

the Avenues to the zoo and ocean. Holy smokey eyes,

what politics of inevitability do not decry le bon temps

roulet remain forever contradictory, insisting the plot

is not the story, the narrative barely the end of the matter.

/ / /

Dark Passage (Delmar Daves, 1946)

It’s never easy, clocking the world, driving

the back roads and waterfront. Yesterday’s

headlines now obsessive scrapbook fodder.

Together they watch for cops, nosey citizens

and night-time denizens. Bandages, undone,

his face, that voice, going back to just prior.

The fall, the money and a six year sentence,

their words falling like Fortian frogs through

the fog. Then, what if, a small bar in Mexico.

Walking through the door, sunshine framing

her to faded perfection. If only his paranoia

would subside. But innocence is invariably

tricky, proof “on the other side,” hardly enough.

Her inherited wealth, Count Basie and a Nob

Hill apartment no more than a coming attraction.

The writer sitting at his desk, staring at a blank

page, disgusted with its whiteness, yearning for

tough mamas and after-hours on the Avenue.

No matter that Philly is written across a series

of comic asides, shoddy sofas and cheap hotels.

If not for second-rate pulpsters and their spit-

balling brethren, where would we be? Ping-

pong with Henry Miller. Insisting he was no

Dashiell Hammett, this no Maltese Falcon.

Instead: those paperbacks, that law suit, and

a camera-eye that tells only half the story.

/ / /

Human Desire (Fritz Lang, 1954)

Her legs crossed, propped

on a dressing-table. Your eye

moves from slip to slippers.

Her right arm across her stomach,

left hand resting on left knee.

Head tilted to the right. Not

yet thirty: if vulnerable, then

contemplative. Or vice versa.

Perhaps a neon hotel, refuge

from everything but the camera.

Lit to highlight the shadows.

Three profiles, two mirrors.

In one an open door, a towel

on a hook. Next to another door,

room or hallway. How many

doors to make a room, to make

an exit? How many mirrors to

reflect the world? How many

profiles to glimpse a likeness?

And who would enter, if jealous

husband, roustabout lover or

predatory boss. She who might

murder, the desire to be human,

so human to desire. The tracks

parallel, meeting, crossing, straight

out of Europe, the entrance like

the exit, through the hallway,

door, shadows, reflection, desire.

/ / /

Phantom Lady (Robert Siodmak, 1944)

Oh, Phantom Hat, worn on the

wrong side of a disturbed mind.

Even poor Henderson, cops

lingering in his apartment, wife

strangled, recalls a hat no one

will corroborate, reduced to:

“Maybe I only imagined that

woman.” Hats like nobody’s

business, blatant, yet universal,

real, if fanciful, with a credit all

its own. Chapeau-noir worn at

a non-existent angle by Jack, his

psychopathic pal. A euphemism

for bonkers? If not those who

bonk? Like Kansas, the secretary

not the state, more than a match

for Cliff, the drummer not the

precipice, who, having absconded

with Jack’s money, paradiddles

himself into a frenzy. More

perturbing is that fucking cop,

Burgess, who, like a spit-roasted

Republican switches sides with

the flimsiest of alibis. Perhaps it’s

the heat, back when courtroom

settings had not yet been turned

into a series of air-conditioned

nightmares. No sweat, but saturated

shadows and oblique confrontations.

None so unsettling as Burgess’s reply

to Jack’s suggestion — self-flattery, of

course — that the killer might well be

a genius. “No,” says Burgess, “he’s a

paranoic. It’s not how a man looks,

but how his mind works. Some day

we’ll have the sense to train the mind

like we train the body.” To which one

might reply, if the hat fits, why in the

world would anyone want to wear it.

/ / /

Where the Sidewalk Ends (Otto Preminger, 1950)

”A cop is basically a criminal,”

with “an instinct for … legalized

violence. Not so much symptomatic

as stating the obvious. Back before

the bald guy entered the picture.

It’s a daddy-thing, I guess. The old

guy works for the man or

the mob, or is there a difference?

Reeking blood brother nemesis.

I didn’t know a guy could hate

that much.” Say, what? Blame

the city, schmuck-face. All that

neon moral ambiguity. Kills the

soul as well as the robbery suspect.

Who never hopped a red-eye

heading for Dreamland. Dumped

the body but not the soul. They

say if you throw an egg from

the Dead Zone nine times out

of ten you’ll hit a fucking Cartesian.

Framing the question, not

the cabbie- his high-flag

drenched in sassafras, headlong

towards an imperfect circle.

Blissed-out rainwater and graveyard

tips. Tight-wadded miracles

frenetically enbedded in a father

who falls for the murdered man’s

wife. As watered down as Luke

the Drifter retching for redemption

cralwing through a cookie jar

delirium. Prompting the great

man to feign ignorance: “I remember

nothing.” Low box office, high

impact, late night fodder, legalised-

something-or-other, without even

a manifesto to fall back on.

/ / / / /

On Dangerous Ground: Film Noir Poems by Woody Haut was published by Close to the Bone Publishing (UK). To acquire a copy via Amazon for $8.99 (paperback), click here. On The Seawall usually does not usually encourage purchasing from Amazon, but we find no other point of sale available for this title.