“I see a postman everywhere”: Elizabeth Bishop’s Postcards, an Exhibition at the Vassar College Libraries

I.

Those of us born around 1980 might be the last generation attuned to the drama of the mail. We were alert, as children, to its twinned sense of urgency and privacy; its sealed envelopes; its conveyance of dreaded bills and relieving checks; its transit by officials in serge blue uniforms, threading the streets in boxy trucks that looked, themselves, like packages; its arrival through the thin mouth of a door-slot or tucked, like a secret valentine or a ballot, into the belly of a box. Mail was a gift economy (especially from aunts), a negotiation between inside and outside, and a secular sacrament of democracy, administered six days of the week. Long before I could vote, I sent letters and indulged my gluttonous diet of books at the public library. Libraries and letters were democracy to me, their protection of knowledge and communication backed by federal law. I had a bibliophile’s appreciation for being American: a patriotism yoked to poems, stories, and the post office.

I knew, even at eight, that to tamper with someone else’s mail merited fines and jail time. My pen pal exchanges — with news of crushes, my basketball team’s weekly glory or annihilation, a particularly good book or breakfast — were safe. The solemnity of the mail, its orderly delivery and the specificity of addressee, also appealed. In a boisterous house of six, I coveted the few things that I did not have to share. Years later, when a member of my household accidentally opened a college letter of acceptance, it took more than four years, and a diploma with only my name on it, to forgive the trespass. Meanwhile my faith in poems, and in letters’ treasure, redoubled. When I discovered that you could read poets’ letters and manuscript drafts bequeathed to archives, I found a path to my doctorate and to years of blissful reading; in the archive, poems’ and letters’ revelations opened for me, across the decades, offering clues to writers’ habits of mind, often startling and riveting at once.

II.

The letters of the poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), whose circumference of influence has expanded every year since her death, spurring four biographies and a fifth in progress, are marvelously good reading. As she wrote to her friends Kit and Ilse Barker in 1953, she found penning a letter “like working without really doing it.” Her epistolary art, and a spell of psychoanalysis in the late ‘40s, might account for the intimate relational aesthetic that appeared in her poems after her first book, North & South (1946), was published. Indeed, her very next book, Poems, which republished North & South and added A Cold Spring, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1956. Yet the true scope of her artistry was not fully evident until scholars began to plumb her burgeoning archive in the decades after her demise, discovering the rich substrate of her writing — letters, notebooks, unpublished poems and prose — that undergirded the work published in her lifetime.

The letters of the poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), whose circumference of influence has expanded every year since her death, spurring four biographies and a fifth in progress, are marvelously good reading. As she wrote to her friends Kit and Ilse Barker in 1953, she found penning a letter “like working without really doing it.” Her epistolary art, and a spell of psychoanalysis in the late ‘40s, might account for the intimate relational aesthetic that appeared in her poems after her first book, North & South (1946), was published. Indeed, her very next book, Poems, which republished North & South and added A Cold Spring, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1956. Yet the true scope of her artistry was not fully evident until scholars began to plumb her burgeoning archive in the decades after her demise, discovering the rich substrate of her writing — letters, notebooks, unpublished poems and prose — that undergirded the work published in her lifetime.

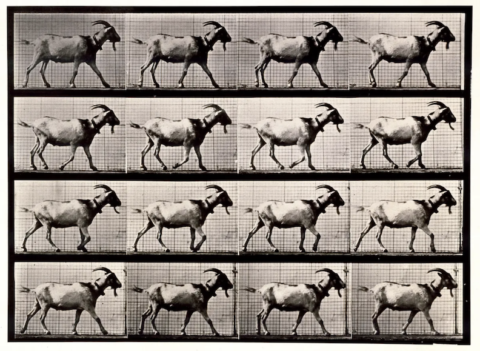

Some of Bishop’s most productive years were spent in Brazil between 1951 and 1966, and late in her career, she noted that her writing process often required mild displacement. On a postcard from January of 1979, which features Eadweard Muybridge’s Goat Walking, she confesses to the poet James Merrill, whom she addresses as “Dear Jimmy,” that she is staying at the oceanside house of the poet John Malcolm Brinnin in Duxbury, Massachusetts, where she finds she can write better:

“I find it much easier to work away from home than “at home” for some reason … It seems to me I’ve rarely written anything of any value at the desk or in the room where I was supposed to be doing it — it’s always in someone else’s house, or in a bar, or standing up in the kitchen in the middle of the night.”

Her poems, like postcards, are spurred by travel and novelty. As if to embrace this restless muse, Bishop’s poems often feature conventions from the media of daily life to include characteristics of the letter and postcard, the newspaper column and television broadcast, the blues song and the family Bible, a travelogue and a nursery rhyme, and even a “Large Bad Picture” painted by a great-uncle (“before he became a schoolteacher,” wisely, we surmise).

Previous editions of Bishop’s correspondence with specific recipients — Robert Lowell, her editors at the New Yorker, and a broad sampling of her letters exchanged with various persons arranged by Robert Giroux in One Art (1994) — as well as an edition of her paintings in William Benton’s book, Exchanging Hats (1996), frame Bishop’s melding, on the one hand, of artistic traditions spanning from classical antiquity to modernist anarchy, and, on the other, conventions and cognitive modes connected to popular culture and media. This ambidexterity has made Bishop seem enduringly modern, and even contemporary, more than 40 years after her death.

We might all envy such an afterlife: one increasingly vivid, celebrated, and relevant. This fall, a new limited edition of Bishop’s postcards, curated by the eminent Bishop scholars Jonathan Ellis and Susan Rosenbaum, has been published by Vassar College Libraries as a companion to an exhibit of 55 of the 570 postcards in her archive at Vassar. (This essay links to a permanent online gallery of 10 of Bishop’s postcards with Ellis and Rosenbaum’s commentaries.) The book and physical exhibition add another prismatic dimension to our understanding of the poet’s sensibility.

III.

As Bishop wrote in her story, “In the Village,” postcards “come from another world, the world of the grandparents who send things, the world of sad brown perfume, and morning.” While that particular story, set in Nova Scotia, concerns disturbing events that led to Bishop’s mother’s psychiatric institutionalization, the child-narrator’s use of “morning” bespeaks both the grief and ritualism that attend daily acts — such as sending or receiving the mail — carried out after loss, even when there is frail hope of reciprocity or response. The homophonic hinge of “morning” also hints at the postal (and psychic) errands that the child-narrator runs later in the story, delivering care packages addressed to her mother to the local post office with her hand held protectively over the hospital address, lest other villagers see it.

As Ellis and Rosenbaum note in their introduction, Bishop often mailed postcards from locales while expressing a longing, on the written (verso) side, to be elsewhere. Or she editorialized the postcard’s depiction of her location, adding captions to the visual image, often ironizing or qualifying it. Thus her postcards, like her poems, frequently enact reality principles against idealized images or convey coded secrets: the poet often keeps her hand, as it were, partially over the message.

In late December of 1948, for instance, she sent a postcard from Key West, Florida, to her friend UT (University of Texas) Summers with a long red arrow pointing to the “large, cheap, wonderful (although ugly) apartment” on Francis Street in which she’d taken up residence. The dismal-looking intersection in Key West contrasts with the bright red ink with which Bishop inscribes her holiday greeting “MERRY CHRISTMAS” and the message on the verso side, which includes, in the Christian season of consequential birth, a query about the gender of the baby that UT was expecting. Arrivals are the subtext of the postcard, its grim cheer suited to the “wonderful (although ugly) apartment” and her friend’s preparations for childbirth.

In late December of 1948, for instance, she sent a postcard from Key West, Florida, to her friend UT (University of Texas) Summers with a long red arrow pointing to the “large, cheap, wonderful (although ugly) apartment” on Francis Street in which she’d taken up residence. The dismal-looking intersection in Key West contrasts with the bright red ink with which Bishop inscribes her holiday greeting “MERRY CHRISTMAS” and the message on the verso side, which includes, in the Christian season of consequential birth, a query about the gender of the baby that UT was expecting. Arrivals are the subtext of the postcard, its grim cheer suited to the “wonderful (although ugly) apartment” and her friend’s preparations for childbirth.

In a campier vein, Bishop’s postcards to Frani Blough Muser, whom she had known since she was 16, include a black-and-white postcard from 1937 featuring tourists in Ireland bending over backward to kiss the Blarney Stone. Bishop gives individual captions to each of the three women gathered by the storied stone, while a group of men hold onto the legs of one man, sprawled on the castle floor, intent on smooching the edifice. Above the three women, including the first figure with short-hair, she writes: “man? Fashion-plate? Ban-shee? … (Adding sex-interest to the B.S.)” And she notes, on the verso side, “We did NOT do this — we happened to be the only people on the tour at the time and did not trust each other’s grip.”

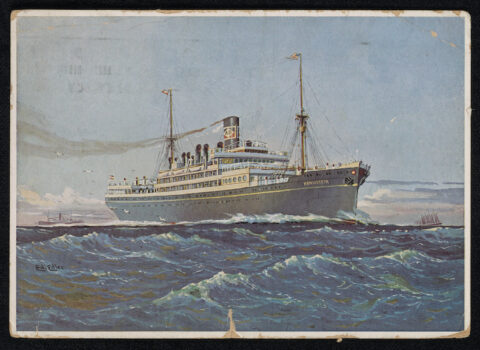

Another more troubling postcard to Muser features a painting of the Königstein, a Nazi freighter Bishop took to Europe in 1935. In her message, Bishop complains about the “German tourists” whom she says “have so trampled over my person & intellect… I just hide away & moan & wait for Antwerp.” The freight (and fright) between Bishop’s lines is audible, though she leavens her situation on the Nazi ship by thanking Muser for send-off gifts: “Your literature has been invaluable—I now know 26 ways of cooking gooseberries, & have several addresses of lonely boys in England, from the ‘Sunshine Corner’ of the Family Herald, whom I shall look up.” The postcard again proves to be a vehicle for situational satire and mild innuendo, however grim the authoring circumstance. Postcards generally seem to have been Bishop’s shorthand for negotiating “betweenness,” keeping in touch with others and, we suspect in reading this volume, keeping track of herself as her coordinates shifted across countries, companions, and continents.

Another more troubling postcard to Muser features a painting of the Königstein, a Nazi freighter Bishop took to Europe in 1935. In her message, Bishop complains about the “German tourists” whom she says “have so trampled over my person & intellect… I just hide away & moan & wait for Antwerp.” The freight (and fright) between Bishop’s lines is audible, though she leavens her situation on the Nazi ship by thanking Muser for send-off gifts: “Your literature has been invaluable—I now know 26 ways of cooking gooseberries, & have several addresses of lonely boys in England, from the ‘Sunshine Corner’ of the Family Herald, whom I shall look up.” The postcard again proves to be a vehicle for situational satire and mild innuendo, however grim the authoring circumstance. Postcards generally seem to have been Bishop’s shorthand for negotiating “betweenness,” keeping in touch with others and, we suspect in reading this volume, keeping track of herself as her coordinates shifted across countries, companions, and continents.

IV.

Examining Bishop’s use of the postcard is further warranted by her reflexive habit of importing postures of everyday writing into the lyric poem, and vice versa: looking at Bishop’s postcards, in which she often indicated paragraph breaks as one would indicate stanza breaks in poems, we see Bishop treating the spatial constraints of a postcard as she might a closed poetic form. In an unfinished forward to Sylvia Plath’s Letters Home (1975), Bishop tellingly notes the difference between letter-writing and telephoning, championing the letter as a rhetorical space, one that improves even the least adept correspondent:

“Writing letters, not telephoning, is, or was, a bit like getting dressed up and going to the symphony concert instead of sitting at home in pajamas and listening to it on the radio: no matter how illiterate, ignorant, or inarticulate, once one takes pen in hand, one has to make an effort; certain formalities are to be observed, unless one was either eccentric or a literary genius.

In her letters, as in her poems, Bishop could partake of both formality and improvisation, courtesy and camp; in the postcard, the letter’s junior cousin, she indulges a paratactic license that, as Ellis and Rosenbaum suggest, has something of Frank O’Hara’s “I do this I do that” mode, which allowed her to echolocate across changing terrains, evolving impressions, and the weather of moods.

In her letters, as in her poems, Bishop could partake of both formality and improvisation, courtesy and camp; in the postcard, the letter’s junior cousin, she indulges a paratactic license that, as Ellis and Rosenbaum suggest, has something of Frank O’Hara’s “I do this I do that” mode, which allowed her to echolocate across changing terrains, evolving impressions, and the weather of moods.

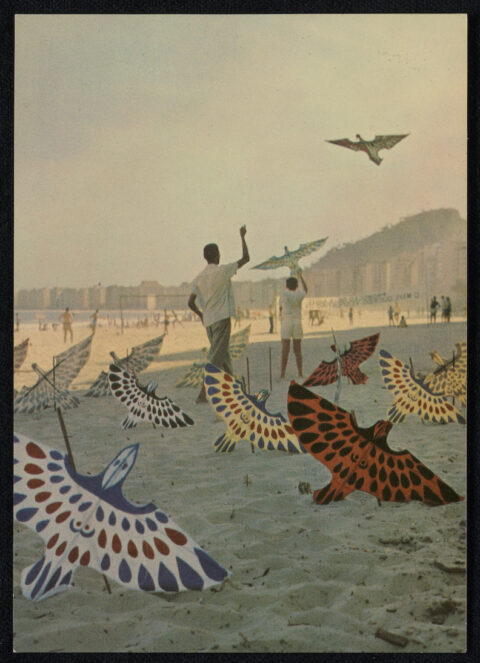

One of her most moving missives in this vein is a postcard from Brazil that features a man and a boy flying large beautiful kites at Copacabana Beach in Rio. Bishop writes to her friends, Loren MacIver and Lloyd Frankenberg, in 1962, opening with the line: “Oh for the wings of a kite to fly to Paris on.” She rues that Lota de Macedo Soares, her partner for over a decade in Brazil, is thoroughly absorbed by her job reclaiming Flamengo Park on the Rio waterfront, a project that will likely take several more years, while Bishop would rather be traveling — to Paris, France, and to Egypt to see the Nile River. Then she indulges in a bit of epistolary scolding:

“You are the World’s Worst Correspondents. For Christmas I’d like nothing better than a nice long letter full of gossip and personalities and that intellectual ferment that’s supposed to exist only in Paris – Why don’t you share a bit of it? …

Who are your favorite French painters? If you see Miss Toklas please give her my regards —”

Bishop’s hunger for “gossip,” “ferment,” and transport is evident — from the dozen bird-like kites on the postcard to her salutations to Gertrude Stein’s retiring partner, Alice B. Toklas, with whom she might feel some kinship as the less charismatic figure in a famous couple. Bishop’s unhappiness is palpable: “Lota is working terribly hard & was given a medal a while ago … [But] parks need centuries, unfortunately.” Within four years, Soares would suffer a nervous breakdown, related to the stress of overwork, political turmoil in the Brazilian government, and her concerns about Bishop’s wavering fidelity.

Poignantly, the postcard on the corresponding page of the exhibition catalogue, dated from 1968, is addressed to a Brazilian friend after Lota’s death (from an overdose of Valium) while she was staying with Bishop in New York City in 1967. The card concludes with Bishop musing: “I miss Lota horribly, more all the time, it seems – not the Lota of the past few years, but the old, well one I was so happy with. I know life will never be so nice again.” It was not the first time Bishop had felt subject to daily grief (“morning”) or bereft of a transitory happiness.

V.

Despite her postcards’ periodic errands of grief, Bishop frequently deployed the postcard to poke fun at her immediate situation or to share a coded joke. She writes to Merrill in 1973 with a postcard featuring a “Saint Day Card,” inscribed in Greek, with a pair of feminine and masculine hands, clasped together, surrounded by a wreath of flowers. She jests, on the recto side: “I’m either congratulating you on yr. engagement, or asking you to marry me … I think.” Bishop’s queering of heteronormative romantic tropes is a frequent postcard feature, one deployed with varying degrees of coyness.

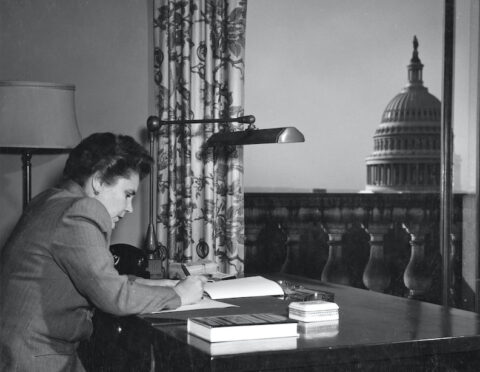

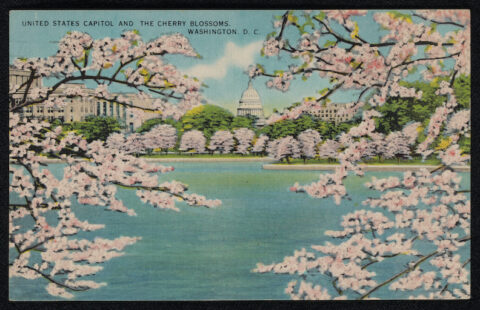

Indeed, queer campiness and subversive critique are both at play in the only postcard-poem Bishop published in her lifetime, “View of the Capitol from The Library of Congress,” a lyric that explicitly imitates the captioning, perspective, and brevity of a postcard to satirize the Cold War’s politics of surveillance and the blare of nationalistic music — two pet peeves of Bishop during her one year of service as Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress (now the office of the U.S. Poet Laureate) from September of 1949 to the fall of 1950.

At 38-years old, Bishop was working her first real job since an inherited legacy was, for much of her life, roughly enough to get by on. Although her duties as Poetry Consultant were not onerous, she found the job exhausting; as she wrote on a postcard to her physician, Dr. Anny Baumann, “I just wish I didn’t get so tired by evening but I suppose now I know how most of the rest of the world feels most of the time.” Bishop had other, more personal reasons to feel depleted: during her term as a federal employee, in a position of public visibility, the Senate Appropriations Committee issued a report entitled “On the Employment of Homosexuals and Other Perverts in Government Office” and Senator Joseph McCarthy began his notorious three-year witch-hunt for “Communists.” Indeed, Thomas Englehardt reports that by 1953, one in every 5 Americans had been subject to a “loyalty-security check.”

From her office at the Library of Congress, Bishop had a literal view of the Capitol Dome from the large picture window by her desk. Living out her amorous life quietly, staying at a Georgetown boarding house, Bishop had become a government employee at a moment in which the Cold War rhetoric of “hygiene” against the “infection” of Communism included the persecution of anyone thought susceptible to blackmail, including homosexuals, roughly 5,000 of whom — according to Lillian Faderman — were dismissed from military or government service between 1947-1950.

From her office at the Library of Congress, Bishop had a literal view of the Capitol Dome from the large picture window by her desk. Living out her amorous life quietly, staying at a Georgetown boarding house, Bishop had become a government employee at a moment in which the Cold War rhetoric of “hygiene” against the “infection” of Communism included the persecution of anyone thought susceptible to blackmail, including homosexuals, roughly 5,000 of whom — according to Lillian Faderman — were dismissed from military or government service between 1947-1950.

Bishop suffered mightily from asthma and was often absent from her post; as the biographer Joseph Frank, who befriended her that year, noted: “Elizabeth certainly had lots of anxieties … I always had the feeling that she didn’t want to talk about anything personal.” Two of Bishop’s postcards in the current exhibition feature the Library of Congress or the U.S. Capitol building: one to her physician, Dr. Anny Baumann, in which she assures her that “Everything is going very well & I have not been DRUNK.” A second postcard, to MacIver, features the cherry trees in bloom, obscuring the U.S. Capitol in the background: it was one of several pictorial postcards that Bishop sent MacIver, a painter, that year.

Tellingly, Bishop waited until she had left her position and Washington, D.C. to enclose her postcard-poem, “View of the Capitol from The Library of Congress,” inside of a traditional letter to MacIver and her husband, Lloyd Frankenberg, who was a conscientious objector. In the five-stanza poem, Bishop parodies the “wall-eyed” vision of Congress, presumably in its hunt for homosexuals and Communists, and the nationalistic pomp of a local Air Force Band. Bishop claims, in her poem, that the trees in the Washington Mall area absorb the clamor of the band: “The giant trees stand in between / I think the trees must intervene,” the speaker surmises. And then, in the last stanza, the speaker addresses the trees themselves, picking up on the visual trope in the postcard to MacIver, in which the cherry trees crowd out the Capitol. Bishop writes, playfully:

Tellingly, Bishop waited until she had left her position and Washington, D.C. to enclose her postcard-poem, “View of the Capitol from The Library of Congress,” inside of a traditional letter to MacIver and her husband, Lloyd Frankenberg, who was a conscientious objector. In the five-stanza poem, Bishop parodies the “wall-eyed” vision of Congress, presumably in its hunt for homosexuals and Communists, and the nationalistic pomp of a local Air Force Band. Bishop claims, in her poem, that the trees in the Washington Mall area absorb the clamor of the band: “The giant trees stand in between / I think the trees must intervene,” the speaker surmises. And then, in the last stanza, the speaker addresses the trees themselves, picking up on the visual trope in the postcard to MacIver, in which the cherry trees crowd out the Capitol. Bishop writes, playfully:

Great shades, edge over,

give the music room.

The gathered brasses want to go

boom–boom.

There is likely a pun in “Great shades,” a reference to both trees and the hallowed dead. Meanwhile, the “gathered brasses” of the Air Force Band, find that although “playing hard and loud […] / the music doesn’t quite come through.” Here, the “boom-boom” percussive beat of patriotic tunes and the sinister music of bombardment is turned cartoonish. But Bishop was keenly aware of the threat that wartime (even Cold Wartime) could bring to the average civilian.

“View of the Capitol from The Library of Congress” was, in fact, the only poem that Bishop finished during her term as poetry consultant, but she used her office — and its window — onto D. C. politics to lodge a stern critique, disguised as what she called a “little number.” Five years later, she would write to her friends Joseph and UT Summers: “I am so surprised that the ‘View of the Capitol’ means something. I was really quite unaware of it … Now I see it does. Please don’t tell anyone this!” Bishop’s mock-horror at the sardonic parody in her poem seems utterly performative; she must have known it was a shot-across-the-bow (or across the consultant’s desk) during a time of great personal discomfort. She later noted, in a letter to Lowell, that her term in Washington had been a “dismal year … when I thought my days were numbered.”

VI.

Bishop survived it and, in 1951, found a more habitable world in Brazil, where Lota built her a writing studio on Samambaia, her mountainside property. Yet the aggregate cost of having to hide aspects of her identity and encode her secrets might have been on her mind in later years. During the slow emergency of Lota’s mental illness and in the years after Lota’s death, Bishop earned a living through teaching posts in the United States, eventually purchasing a condominium on Lewis Wharf in Boston.

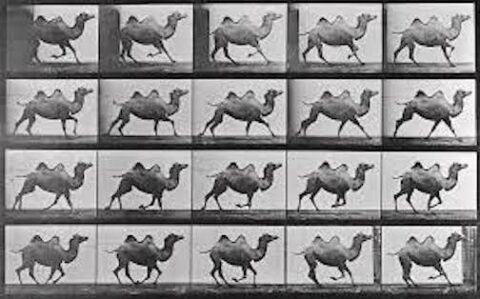

In what would be her last decade, the poet took stock of what she had accomplished and what had not yet been achieved. In 1978, for instance, she sent Merrill another postcard with a montage by Muybridge, one featuring a Galloping Camel (1887). On it, she rues that “Letter-writing seems to be my lost art – well, and so is poetry-writing, I’m afraid, or almost. There is always too much to say.” Here, she is not describing typical writer’s block: it seems to be the opposite. The quantity of the “said” to the “unsaid” and the “written” to the “unwritten” becoming, perhaps, its own inhibition as Bishop’s accumulated knowledge of the world, over her six and a half decades, chafed against her sense of waning time and energy.

In what would be her last decade, the poet took stock of what she had accomplished and what had not yet been achieved. In 1978, for instance, she sent Merrill another postcard with a montage by Muybridge, one featuring a Galloping Camel (1887). On it, she rues that “Letter-writing seems to be my lost art – well, and so is poetry-writing, I’m afraid, or almost. There is always too much to say.” Here, she is not describing typical writer’s block: it seems to be the opposite. The quantity of the “said” to the “unsaid” and the “written” to the “unwritten” becoming, perhaps, its own inhibition as Bishop’s accumulated knowledge of the world, over her six and a half decades, chafed against her sense of waning time and energy.

Within a year of penning this postcard, Bishop had died of an aneurysm. And what she had managed “to say” in both her published and unpublished work would take decades to assess. In a poem entitled “Dream—”, for instance, one that was published posthumously, the poet conjures a celestial postman carrying “A mammoth letter in his hand / Postmarked from a foreign land.” We learn, entering the associative logic of the dream, that “The letter is of course from you,” yet the dutiful postman “has trouble with this letter / Which constantly grows bigger & bigger.” Eventually, the postman disappears into the “blue, blue air” without delivering the grown-in-girth missive from some desired friend or beloved.

So too, Bishop’s readers might “see a postman everywhere” as the correspondences she crafted between poems and the media of postcards, letters, newspapers, songs, maps, broadcasts, and paintings created an oeuvre of uncanny verisimilitude for our own world. The epistolary network, moreover, that she cultivated throughout her life — with school friends and aunts, neighbors and colleagues—intertwined her art and life long before those narratives found new berth in archives, biographies, and editions of her work. As this exhibition indicates, we are still in receipt of Bishop’s dreamt-of-letter, the postman of the “blue, blue air” replaced by diligent scholars, archivists, and critics delivering the enlarging missive of Bishop’s legacy to readers eager for her exquisite “gossip,” “ferment,” and artistry.

/ / / / /

“Elizabeth Bishop’s Postcards: An Exhibition” is shown at Vassar College’s Thompson Library from September 18 – December 15, 2023.

The postcards:

1 / Postcard to James Merrill, Goat Walking, 1872-85, Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904)

2 / Postcard to UT Summers. Photograph of Francis Street, Key West, Florida. December 18, 1948

3 / Postcard to Frani Blough Muser. Painting of Königstein. August 24, 1935

4 / Postcard to Lloyd Frankenberg and Loren MacIver. Photograph of Copacabana Beach, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. 1962

5 / Postcard to Mrs. Lloyd Frankenberg (Loren MacIver). United States Capitol and the Cherry Blossoms, Washington DC. April 2, 1950

6 / Postcard to James Merrill, Bactrian Camel walking, 1872-1885, Eadweard Muybridge