Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo Reconsidered

Published in 1955 to great acclaim, Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo made possible the wave of novels that graced Latin American fiction in the 1960s, from Carlos Fuentes’s The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962) to Mario Vargas Llosa’s In the Time of the Heroes (1963) to the monumental One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) by Gabriel García Márquez. Yet despite its broad influence, Pedro Páramo is a very different novel from the those mentioned above and Juan Rulfo a novelist who stood apart from the boom and never fully participated in it. Born in the state of Jalisco in 1918, he witnessed first-hand the violent peasant and Cristero revolts of the 1920s, events that would have a profound influence on his work. Besides Pedro Páramo, he published the short story collection The Burning Plain in 1953 and nothing else during his lifetime. [1]

I first learned of Pedro Páramo in Nicanor Parra’s writing workshop at Columbia University, which I briefly attended back in the early 1970s. One of the participants, the Chilean Randolph Pope if I remember correctly, recommended it to me as the first of many books that composed the archipelago of works now known as the “Latin American boom.” Procrastinator that I was, I put Randolph’s recommendation in the back of my mind until a couple of years later when another friend sent me a copy of Juan Rulfo’s book urging me to read it. I put my procrastination aside and began to read.

Pedro Páramo opens with the sentence: Vine a Comala porque me dijeron que acá vivía mi padre, un tal Pedro Páramo [2] and goes on to describe a deathbed scene in which the narrator’s mother asks him to visit his father and seek redress for his neglect. After her request, she dies holding the reluctant narrator’s hands. He says, “I just kept at it until I had to struggle to free my hands from hers, which were now without life.” A couple of paragraphs later comes an astonishing revelation that offers the key to the reading of the novel:

“I never thought I’d keep my promise. Until recently when I began to imagine all kinds of possibilities and allowed my fantasies to run free. And that’s how a whole new world started swirling around in my head, a world built on expectations I had for that man named Pedro Páramo, my mother’s husband. That’s why I came to Comala.”

“I never thought I’d keep my promise. Until recently when I began to imagine all kinds of possibilities and allowed my fantasies to run free. And that’s how a whole new world started swirling around in my head, a world built on expectations I had for that man named Pedro Páramo, my mother’s husband. That’s why I came to Comala.”

If we assume that the narrator is clueing us in to what makes the story coalesce — fancy rather than intellect, illusion rather than reality — then the paragraph reveals that the novel is erected on the wings of the narrator’s hope. Make no mistake, Juan Preciado tells us, the story I am about to tell you makes no claim on the world of actual events but revolves around the world of illusion. That this hope soon becomes spectral, indeed unlike any hope we are used to, is the first of many mysteries the novel presents.

Intrigued by the simplicity of the language and the complexity of the narrator’s thoughts, I read on. On his way to Comala to see his father, the narrator, whose name is Juan Preciado, encounters a mule driver who also happens to be a son of Pedro Páramo. Pedro Páramo, Juan Preciado learns from his half-brother, is dead, and this piece of information unleashes a narrative where time breaks into a thousand pieces, illusion and reality coexist, and fancy, rather than reason, moves the story.

Juan Preciado reaches the town of Comala in search of his father, the man called Pedro Páramo, and realizes the town itself is populated by the dead. In an interview with Waldemar Dante, Rulfo said that “the story begins by being narrated by a dead man who tells it to another dead man who tells another dead man. It is a dialogue among the dead in a dead town.” Amazingly, we find ourselves in a realm where time does not exist and the temporal sequencing we are used to in traditional fiction is upended. Much of the narrative takes place in a past that appears before us as coexisting with the present, challenging our conception of time, both actual and imagined, wrecking our expectations and forcing us constantly to reposition ourselves in relation to the text. Time present and time past blend and become one, or become none. Events come and go and characters leap from one scene to another. Memory and actuality are held together by chaos. But the book itself is not chaotic. Rather, it is the characters’ variable and sometimes contradictory drives and impulses that propel the story to its ineluctable end, the crumbling of Pedro Páramo, “as if he were a pile of rocks.”

Pedro Páramo is not an easy book, but a relentlessly compelling one. I remember reading it in one day as García Márquez had done before embarking on the writing of One Hundred Years of Solitude, then rereading it repeatedly for years after though I never managed to memorize it as he had done. García Márquez rightly calls Pedro Páramo “a poetic work of the highest order.” The erasure between the lyric and narrative drives is something I aspired to achieve in my own work, but it wasn’t until I read Rulfo’s novel that I learned how to do it. In my novel The Cigar Roller (Grove, 2005), the main character remembers events from his past which are more vivid than his present, making the latter a mere stage where his life is played out. In Cubop City Blues (Grove, 2012) the interpenetration of past and present reaches a crescendo in the mind of the main character, a blind adolescent boy, and his attempts to break out of his sequestered life through the act of storytelling.

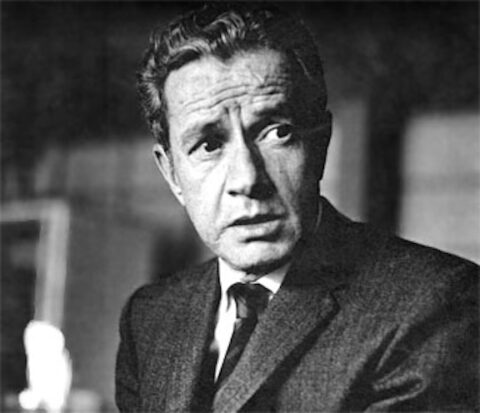

[Left: Juan Rulfo] But back to Pedro Páramo. The town in which the action takes place is Comala, a name derived from the word comal, the earthenware pot used to heat tortillas over a fire. The town’s weather is hot, unbearably so. The landscape is a barren expanse of plains bordered by hills, reminiscent of Hemingway’s story “Hills Like White Elephants”: “The plain resembled a translucent pool in the pulsing heat of the sun, dissipating in the distance where a gray horizon took shape. And beyond that, a line of mountains. And even farther still, a never-ending distance.” Can Rulfo be describing a vision of hell? On the next page the mule driver describes their father Pedro Páramo as “bitterness incarnate” and the embodiment of a cacique, a Latin American strongman, whose narrow vision does not allow him to care about anyone but himself.

[Left: Juan Rulfo] But back to Pedro Páramo. The town in which the action takes place is Comala, a name derived from the word comal, the earthenware pot used to heat tortillas over a fire. The town’s weather is hot, unbearably so. The landscape is a barren expanse of plains bordered by hills, reminiscent of Hemingway’s story “Hills Like White Elephants”: “The plain resembled a translucent pool in the pulsing heat of the sun, dissipating in the distance where a gray horizon took shape. And beyond that, a line of mountains. And even farther still, a never-ending distance.” Can Rulfo be describing a vision of hell? On the next page the mule driver describes their father Pedro Páramo as “bitterness incarnate” and the embodiment of a cacique, a Latin American strongman, whose narrow vision does not allow him to care about anyone but himself.

If we assume that the narrator is telling us something about his relationship to his father (or the absence of a relationship), then we can approach the story as a study of a neglected son who seeks not just redress for the injustices he and his mother have suffered over the years, but also a connection with his roots, with his origins. The search for the father that begins at the individual level broadens later in the novel, when the revolutionary army appears wanting to take over Pedro Páramo’s lands, to include a searing — and very Mexican — critique of national identity. In other words, the wall between psychological and social motivation has been breached and character and nation have somehow coalesced. The revolutionaries, with their allegiances in tow like so much chattel, sell themselves to Pedro Páramo for one hundred thousand pesos and three hundred of his men, who join the revolt because, their leader El Tilcuate says, he likes a good fight.

But this is not all there is to Pedro Páramo. It is as well a bildungsroman, a mystery story, a ghost story, and a love story — all in the space of a little over 100 pages. Its brevity complements its density, and its density, in turn, compresses the narrative into something akin to poetry. To a young writer like me, mired in exile from his native land, this was a fantastic and magical technique I could use to tell my stories; as an older writer, Pedro Páramo remains a grand literary achievement, one that I invoke with every line and sentence I write.

[1] Two recent events reignited my long-standing admiration for Rulfo’s masterpiece Pedro Páramo; first, the publication in 2023 of Douglas Weatherford’s new English version and, more recently, the release of the film version of the novel in late 2024, directed by Rodrigo Pietro from a screenplay by Mateo Gil.

[2] “I came to Comala because I was told my father lived here, a man named Pedro Páramo.” Unless otherwise indicated, all English quotations are from Douglas Weatherford’s worthy translation, published by Grove Press in 2023.