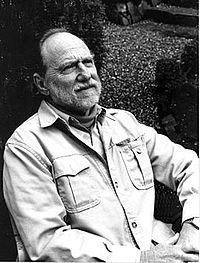

Leonard Nathan, who died in Marin County on June 3, 2007, was one of the most accomplished poets of his generation, but his work is unfamiliar to almost all of the younger poets I correspond or talk with. Think of him as a member of the generation that includes Galway Kinnell, Gregory Corso, Denise Levertov, Kenneth Koch, Phil Levine, Paul Blackburn, Richard Wilbur, Allen Ginsberg, Anne Sexton, W.D. Snodgrass, James Merrill, Cid Corman, Gerald Stern, Richard Hugo, John Ashbery, James Dickey, Alan Dugan, Robert Creeley, W.S. Merwin, Howard Nemerov, Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler — all born in the 1920’s.

Leonard’s first book, Western Reaches, was published in 1958 by Talisman Press. In 1964 Random House published Glad and Sorry Seasons, in 1969 Wesleyan published The Day the Perfect Speakers Left, and in 1975 Princeton issued Returning Your Call. Then came his three books from Pitt, including Carrying On in 1984, a new and selected volume. His final three books were published by Orchises Press. There were other books and chapbooks along the way, including collaborative translations of Aleksander Wat and Cees Nooteboom. His prose included Diary of a Left-Handed Bird Watcher and an introduction to Milosz’s work entitled The Poet’s Work.

A graduate of UC-Berkeley (BA, MA, Ph.D in English), he chaired the school’s Department of Speech from 1968 to 1972, and then managed its transition to the Department of Rhetoric.

When I was a grad student at the University of Wisconsin in the mid-70s, a professor of English who earned her doctorate at Berkeley told me that Leonard’s politics were “ugly.” Leonard wouldn’t have been sufficiently demonstrative or self-righteous in the late-60s Berkeley mode. He loved individuals but was skeptical about humanity and its institutional promotion (by church or Congress or counterculture) of higher-than-ordinary levels of consciousness. Comprehension was something one worked toward, slowly through a lifetime of work.

When I was a grad student at the University of Wisconsin in the mid-70s, a professor of English who earned her doctorate at Berkeley told me that Leonard’s politics were “ugly.” Leonard wouldn’t have been sufficiently demonstrative or self-righteous in the late-60s Berkeley mode. He loved individuals but was skeptical about humanity and its institutional promotion (by church or Congress or counterculture) of higher-than-ordinary levels of consciousness. Comprehension was something one worked toward, slowly through a lifetime of work.

Some time in the early 70s, Leonard published an essay in Shenandoah called “The Private ‘I’ in Contemporary Poetry.” The essay looks at Ben Jonson’s “On My First Sonne” and Wordsworth’s “There Was A Boy” which “asks of us a far less qualified response than Jonson’s.” Where Wordsworth’s poem is primarily expressive, “consciousness itself in the process of operation,” loosening up in form, Jonson’s poem moves “from grief to a comprehension of grief,” the poet aiming to do more than offer an expression of feeling. His point wasn’t to disparage the Romantic impulse, a la Yvor Winters. Instead, he wanted to show that the contemporary poem, of Kinnell and Levine and Ashbury, “is not spontaneous utterance spoken directly out of actual experience, but rather a deliberate and artful form of creating the illusion that spontaneous utterance is spoken directly out of actual experience, because its main aim is pathos and the convention that pathos seems to demand is the personal voice and loosened form and structure.”

In other words, Leonard asked us to write with an ear for the rhetorical, with an awareness of tradition, and with a commitment to the communicative even as we pile on the expressive. In this way, Leonard embodied the tension between two traditions often regarded in academia during his lifetime as mutually exclusive. His work was contemporary in its concerns and personality — but mindful of its responsibility to state a point of view, quite often ironic. His formality was in the shape of his arguments, his diction, the regularities of his line. His style didn’t inspire new trends and his identity didn’t play to the prejudices of the next generation.

CONFESSION

All right then — I am Napoleon

And you, you’ve got to be Joan of Arc.

I’ve just fallen back through a winter of ice,

Done in by a sublime vision of one world.

And you’ve come home from a hard day of torture,

Dragging chains, still defying the Establishment.

Now you can understand my rotten mood and I

Can appreciate your haggard, put-upon look.

And they think our miseries are commonplace miseries,

That we bought them from a marriage counselor second hand!

You go on pressing your palms to that heaving breast,

I’ll just stand here gazing out over the world.

Increasingly, a tone of conversational disillusion came to dominate his poetry. He reached his mature voice in Returning Your Call, and his Pitt books were among the most entertaining, moving, and deft collections that press has ever published.

PILLOW BOOK SONG

The Lady Izumi

Shikibu,

A fragrant blur

In this wavering dream

Of sleeves, bent

Her moon face

Closer, till I

Assumed a love

As soft and subtle

As mist, but she

Said flatly: “It’s time

To give me your life,”

And that seemed so ancient

A habit here

That I was about

To say yes, yes,

When simple moonlight

Saved me, opening

My eyes, sitting

Me up, sodden-

Headed, belly

Packed with ice,

Mouth poisoned,

And so bitterly

I said at the moon:

“I don’t know

Any Lady

Shikibu.”

Leonard’s work never entirely surrendered to the placid, his speaker never gave in to conclusive insight. In the poem above, it’s “simple moonlight” that saves him, not the dream. But, he admits, that does leave him bitter. In this way, you find both the sweet and the sour in Leonard’s poetry.

His tone was that of a small man considering big things; the perspective lent itself to the tragicomic. His topics were mainly domestic, the narratives situational. Of all the poets’ names mentioned above, no one wrote with such stubborn maneuvers of self-dissection, blunt wit, sharpness of phrase, and economy of line. Alan Dugan perhaps, and David Ignatow in a way. But Leonard, with his Jewishy-Chinesey tones, cranky and wise, was more consistently balanced (a hard act) between the communicative and the expressive. Alert poise, amused curiosity.

His last books from Orchises Press, The Potato Eaters, Tears of the Old Magician, Restarting the World, show a master of the short lyric at work.

MOVING FATHER TO THE REST HOME

To father, bound for the rest home, it’s all over,

even the shouting as he watches us

sort through and judge the leavings of his life:

faded photos, expired medicines,

pajamas held up by safety pins,

cheerful get-well cards from the long dead.

We sit on the floor and pronounce — not this, this

perhaps. A few we hold awhile longer

before we shrug and let them slowly drop.

When the word “I” appears in Leonard’s poetry, it rarely takes on more weight than “you” or “we” or “they.” But this isn’t modesty. Leonard’s poetry was ambitious; its pride was in its freedom to say whatever it wanted to say, all the while preserving a rhetorical poise, a withholding of gestures that would merely reflect credit on one’s depth of emotion.

There is also something like a belief at work that verbal dexterity, an attractive way of speaking candidly, can win the day. There is some preening, too. But always, a belief in the ultimately moral nature of speech, the centrality of the word for a cultured man in a shaky culture.

There is also something like a belief at work that verbal dexterity, an attractive way of speaking candidly, can win the day. There is some preening, too. But always, a belief in the ultimately moral nature of speech, the centrality of the word for a cultured man in a shaky culture.

It was disappointing to see that the new anthology of poetry from Pittsburgh ignored Leonard’s poetry. I suggest that you find copies of Dear Blood and Holding Patterns, published by Pitt in 1980 and 1982 respectively.

I spoke with Leonard for the last time about a year ago. He had been on meds for aphasia, loss of memory. But he sounded quite lucid on the phone. Only a few months previously, we had worked together on shaping the final version of the manuscript for Restarting the World. So of course it was a shock to hear that Alzheimer’s had so swiftly robbed him of his wonderful mind. He, too, went to live in an eldercare facility, and he died there.

Loyal friend, devoted teacher, wiseguy and provocateur, Leonard was utterly unique. I miss him dearly.

Last Books of Leonard Nathan

I agree with all that Ron Slate said. As Leonard’s publisher and friend, I miss him very much.

The Potato Eaters, Tears of the Old Magician, and Restarting the World, Leonard’s last three books, are still in print at $12.95, $14.95, and $14.95 respectively ($2.13 for shipping–any quantity; Orchises Press, Box 20602, Alexandria, VA 22320-1602). Anyone who would like to read more of Leonard’s verse is, of course, welcome to order these titles from the press.

He had an exquisite tact and sensibility, exhibits a flawless mastery of form, and writes short, moving and apparently simple (but really complex) poetry that gives any reader immediate and long-term rewards.

R. I. P.

Roger Lathbury

Orchises Press

lathbury@gmu.edu

leonard nathan

I hadn’t heard he died. I first read his work a couple years ago and thought it was wonderful.

appreciate the posting here.

Very good post, thanks a

Very good post, thanks a lot.

Nathan

Thank you for this introduction to a poet I’ve never read, in fact never heard of.

Request for essay

Dear Ron, I’d love a copy of the essay you mention and offer to send on request. Please send to me at ma.mayer@verizon.net. A dozen years ago, Leonard Nathan’s poems taught me, moved me, to study and write poetry. The first poem of his I read has remained a talisman for me. Now I’m pleased to say that I’ve completed a translation of “From The Mountain into German”. “Vom Berg” will likely be published next Fall. This past Winter, it was also included in a tenth anniversary memorial tribute to the victims of the 1999 avalanche in Galtuer, Austria, which claimed almost forty lives.

Do you know which of his work has been translated? The only work that I’ve heard has been translated (into Dutch?) is Diary of a Left-Handed Bird Watcher. Any info you could share will be appreciated. His naturalistic sensibility seems so suited for an international audience.

I appreciate your commentary, and thank you so much for a copy of his essay.

Best Regards,

Mary Ann Mayer

43 Pleasant St

Sharon, MA 02067

ma.mayer@verizon.net