We forlornly ask about ourselves, Is this what it means to be human? Knowing we do this, novelists create unlikeable narrators in order to expand our consciousness of the squalid and the vile. New novels by Rikki Ducornet and Vladimir Sorokin extend this ignobly noble literary tradition. Their limited first-person narrators simply assume that we understand and even suffer over their troubles. Their behaviors are natural to themselves. Although we recoil, we keep reading. What is the nature of our pleasure?

The narrator of Ducornet’s eighth novel, Netsuke, is a psychoanalyst who routinely has sex with his female patients. The shrink introduces himself without delay: “The Practice is the inevitable extension of my own private dilemma. It is lethal, and yet without it I would perish.” He also presents his wife of ten years, Akiko: “She is the white noise I have come to depend upon and possibly cannot live without.” The occasion for his self-display is his project: “I am writing a book … The tough question is, dare I reveal the nature of my investigations; dare I, finally, openly discuss Spells.” Spells is the name given to the office in which he ‘treats’ his erotic patients; in Drear, his other office, he sees the ordinary ones.

The narrator of Ducornet’s eighth novel, Netsuke, is a psychoanalyst who routinely has sex with his female patients. The shrink introduces himself without delay: “The Practice is the inevitable extension of my own private dilemma. It is lethal, and yet without it I would perish.” He also presents his wife of ten years, Akiko: “She is the white noise I have come to depend upon and possibly cannot live without.” The occasion for his self-display is his project: “I am writing a book … The tough question is, dare I reveal the nature of my investigations; dare I, finally, openly discuss Spells.” Spells is the name given to the office in which he ‘treats’ his erotic patients; in Drear, his other office, he sees the ordinary ones.

Writing about Ducornet’s novels, Brian Everson says, “Her work replicates the enchantment we felt when hearing fantastic stories as children or when we first fell into books considered too mature for us … [It] spools out the struggle between the doctrinaire impulse to control and contain … and the more dynamic (albeit sometimes equally dangerous) impulse to transgress, struggle, and create.” That child-like enchantment is the subject of her splendid 2003 novel Gazelle. Her characters are portrayed with the aspects of archetypes – but her ability to render their psychological states allows them to appear modern and recognizably human. It’s a walkable distance from Hesse to Ducornet.

In Netsuke, the analyst makes a mythic pronouncement: “I am the spirit of negation.” But he also talks of his youth and a mother who treated him with disregard. Ducornet thus sets up the book’s oppositions. In her garden, Akiko gazes “for hours at a thing to assure some perfection invisible to me.” Meanwhile, the analyst exposes us to his “hatred for all the lands of milk and honey … I was bred to anger, born and bred to rage.”

Directly stated, such defining attributes may seem to close off the potential for complexity – but Ducornet knows intuitively when to shift from the generalized framing of the mythic tale to the specifying habits of the novel. For instance, the analyst is also capable of stating, “To be healthy one needs to bring the disparate parts of one’s puzzle together and in this way defuse prevailing habits, promiscuity’s fevers.” He describes an evening at home with Akiko. But just when we might empathize or identify with his situation, he gives us a reason not to. There is “the Cutter,” a patient who slashes herself: “The first time the Cutter showed up she was wearing five-inch heels and jeans so tight I could see the swell of her mons pubis. In other words, she presented herself as a woman who was fuckable, and that her fuckability mattered to her more than anything else.” Later, there is David Swancourt, aka Kat, a trans-sexual. The reader, a reserved voyeur, is situated with them in Spells. “Fucking, at its best, is silent,” the narrator says. “And yet what I have learned from my Practice is this: people want to talk about it all the time.”

Directly stated, such defining attributes may seem to close off the potential for complexity – but Ducornet knows intuitively when to shift from the generalized framing of the mythic tale to the specifying habits of the novel. For instance, the analyst is also capable of stating, “To be healthy one needs to bring the disparate parts of one’s puzzle together and in this way defuse prevailing habits, promiscuity’s fevers.” He describes an evening at home with Akiko. But just when we might empathize or identify with his situation, he gives us a reason not to. There is “the Cutter,” a patient who slashes herself: “The first time the Cutter showed up she was wearing five-inch heels and jeans so tight I could see the swell of her mons pubis. In other words, she presented herself as a woman who was fuckable, and that her fuckability mattered to her more than anything else.” Later, there is David Swancourt, aka Kat, a trans-sexual. The reader, a reserved voyeur, is situated with them in Spells. “Fucking, at its best, is silent,” the narrator says. “And yet what I have learned from my Practice is this: people want to talk about it all the time.”

He asks, as we do, “What happens when a doctor sleeps with a patient? And the patient keeps paying the doctor for the other things they do together, the journey into pain and loss and mysterious crimes too terrible to recollect. Is the doctor, then, the patient’s whore?” At this moment, the distance between shrink and audience is narrowed to some degree. He knows the answer – but waits to feel the full force of its damage. In this, too, even with our foreknowledge, we are complicit.

Of course, Ducornet knows that we bring to her novel a firm view of an analyst’s moral responsibility to a patient. If anything, her main character’s actions and statements reconfirm this a priori value. He is despicable. But he also attracts and holds our attention through his use of language: the blend of the clinical and the confessional. Ducornet is telling us: this is what the profane sounds like today.

Of course, Ducornet knows that we bring to her novel a firm view of an analyst’s moral responsibility to a patient. If anything, her main character’s actions and statements reconfirm this a priori value. He is despicable. But he also attracts and holds our attention through his use of language: the blend of the clinical and the confessional. Ducornet is telling us: this is what the profane sounds like today.

* * * * *

Writing about an “amazingly blasphemous” passage in Philip Roth’s Sabbath’s Theater, James Wood notes, “This sentence is really dirty, and partly because it conforms to the well-known definition of dirt – matter out of place, which is itself a definition of the mixing of high and low dictions.” The description of Mickey Sabbath sucking the breasts of his Croatian lover, Drenka, could have been drawn more simply, but the complexity enacts “the exuberance, the hasty joy and chaotic desire, of sex,” delays the punch line, and smudges the line between Mickey’s thoughts of lover and mother. (Mickey is another unlikeable character but described by another critic as “too alive to succeed at dying.”)

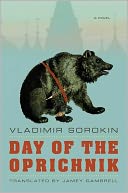

Exuberance – of language, appetites and passions – characterizes the tone and plot of Vladimir Sorokin’s twelfth novel, Day of the Oprichnik. The run-time of the story is a single day in the life of Andrei Danilovitch Komiaga, a member of Russia’s secret police in the year 2028. “Oprichnik” in old Russian means “a special one,” and the Oprichniks, managed by their revered leader Batya, are those to whom anything is permitted as they carry on the thuggish work of the state.

Exuberance – of language, appetites and passions – characterizes the tone and plot of Vladimir Sorokin’s twelfth novel, Day of the Oprichnik. The run-time of the story is a single day in the life of Andrei Danilovitch Komiaga, a member of Russia’s secret police in the year 2028. “Oprichnik” in old Russian means “a special one,” and the Oprichniks, managed by their revered leader Batya, are those to whom anything is permitted as they carry on the thuggish work of the state.

In a 2007 interview in Der Spiegel, Sorokin said outspokenly, “We still live in a country that was established by Ivan the Terrible … Nothing has changed when it comes to the divide between the people and the state. The state demands a sacred willingness to make sacrifices from the people.” In his novel, Russia is again ruled by His Highness and has passed through the “Red troubles” and the “White troubles.” The Oprichniks drive around in red “Mercedovs” and have official seals of the state implanted as microchips in their hands. The religion of the Orthodox church is invoked at public floggings. Komiaga is dressed by his grooms in “a white undergarment embroidered with crosses, a red shirt with collar buttons on the side, a brocade jacket with weasel trim, embroidered with gold and silver thread, velvet pants, red boots of Moroccan leather fashioned with wrought copper soles … a black, floor-length, wadded cotton caftan made of rough broadcloth.” The Czarist past is embodied in his uniform.

The story opens with Komiaga’s morning rituals and moves quickly to an Oprichnik attack on the estate of a rich nobleman who soon sways in a noose from his own gateway. Komiaga describes their action as follows:

The story opens with Komiaga’s morning rituals and moves quickly to an Oprichnik attack on the estate of a rich nobleman who soon sways in a noose from his own gateway. Komiaga describes their action as follows:

“This work is – passionate, and absolutely necessary. It gives us more strength to overcome the enemies of the Russian state. Even this succulent work requires a certain seriousness. You have to start and finish by seniority. So this time, I’m first. The widow of the now deceased Ivan Ivanovich thrashes on the table, screaming the moaning. I rip off her dress, tear off her intricate lace undergarments. Poyarok and Sivolai force her smooth, white, well-tended legs open, and hold them. I love women’s legs, especially their thighs and toes. The wife of Ivan Ivanovich has pale thighs, a bit cold, but her toes are tender, well formed, with well-kept toenails covered in pink nail polish. Her weak legs squirm in the strong Oprichnik hands, and a slight shiver runs through her toes; they splay and stiffen from tension and fear. Poyarok and Sivolai know my weaknesses: they hold her tender, trembling foot near my mouth; I gather the shaking toes between my lips, and launch my bald ferret right into her wombs. How sweet!”

Sorokin says that the downfall of magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky is not the model for Ivanovich’s demise – but such dispossessions of wealth by Putin et al. are “almost a daily occurrence.” As for the Oprichniks’ obsession with enemies of the Russian state, Sorokin believes the Russians, dispossessed of their far-flung U.S.S.R. holdings, talk now “about Russia being a fortress. Orthodox churches, autocracy and national traditions are supposed to form a new national ideology. This would mean that Russia would be overtaken by its past, and our past would be our future.”

Sorokin says that the downfall of magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky is not the model for Ivanovich’s demise – but such dispossessions of wealth by Putin et al. are “almost a daily occurrence.” As for the Oprichniks’ obsession with enemies of the Russian state, Sorokin believes the Russians, dispossessed of their far-flung U.S.S.R. holdings, talk now “about Russia being a fortress. Orthodox churches, autocracy and national traditions are supposed to form a new national ideology. This would mean that Russia would be overtaken by its past, and our past would be our future.”

Nevertheless, just as with Netsuke, many readers will allow the detestable narrator to make a claim on them. He has as much relish for his swaggering position as Oprichnik as Mickey Sabbath has for scandalizing bourgeois morality — and it is his language, given to a sort of adrenalin-soaked officialese shading into overblown, worshipful praise for his work and Mother Russia, that powers his narrative.

Sorokin is a wickedly comical satirist. His derision lurks. Komiaga drives and flies from one duty to the next. The Oprichniks dine together every night and, if Batya so arranges it, they may go together into the hot baths and take narcotics. In a final event, the Oprichniks are treated to a Viagra-like substance:

“The Oprichniks genitals have been kindled, each with its own light … The great strength of the Oprichnik brotherhood lies here. Oprichniks all have genitals revamped by ingenious Chinese doctors. Light flows from the genitals, crabbing manly love. It gathers strength from the rising member. And until the light has waned – we, the Oprichniks, are entwined in brotherly embraces. Strong hands grasp strong bodies. We kiss one another on the lips. We kiss silently, like men, without any women’s sweet talk. We greet and excite one another through our kissing. The bath attendants bustle among us with clay pots filled with Chinese ointments. We scoop out the thick, aromatic ointment and spread it on our members.”

The Oprichniks then form a conga line called “the caterpillar,” coupled via their penises, march around, and enter a pool while roaring “Hail! Hail!”

Sorokin’s work was banned until 1989 when some of his stories were published in a Latvian magazine. (He was born near Moscow in 1955.) He says, “In the days of Brezhnev, Andropov, Gorbachev and Yeltsin, I was constantly trying to suppress the responsible citizen in me. I told myself that I was, after all, an artist. As a storyteller I was influenced by the Moscow underground, where it was common to be apolitical… I held fast to that principle until I was 50. Now the citizen in me has come to life.”

Sorokin’s work was banned until 1989 when some of his stories were published in a Latvian magazine. (He was born near Moscow in 1955.) He says, “In the days of Brezhnev, Andropov, Gorbachev and Yeltsin, I was constantly trying to suppress the responsible citizen in me. I told myself that I was, after all, an artist. As a storyteller I was influenced by the Moscow underground, where it was common to be apolitical… I held fast to that principle until I was 50. Now the citizen in me has come to life.”

One of the Oprichniks boasts, “Not just one diplomat was expelled from Moscow, not just one journalist was thrown from the television tower and not just one whistleblower was drowned in the river.” Sorokin has made his Oprichniks so unlikeable that, given the fate of journalist Anna Politkovskaya, one worries for his safety. But perhaps it is true after all, as Sorokin has suggested, that the Kremlin no longer worries much about its intelligentsia.

[Netsuke by Rikki Ducornet, published by Coffee House Press on May 3, 2011. 128 pages, $14.95 paperback original

Day of the Oprichnik by Vladimir Sorokin, published by Farrar Straus & Giroux on March 15, 2011. 192 pages, $23.00 hardcover]

Two reviews

Oh dark, dark! Neither book inspires my urgency to dive between its covers and fathom it for carnal or blood lust or even wholesome literary curiosity. Just wanted to say, Ron, the reviews as always are fine works. How in the world do you manage to read so goddamn much!