In “Cosmos,” the fourth poem in Katherine Soniat’s A Raft A Boat A Bridge, the speaker recalls a sleepless night (“I toss my leg over a pillow”) caused by physical pain. But the poem’s unease shifts between the bodily and something indistinct but looming. That day she had been poking around a “deserted villa” up the road – “I trespassed, one step after another / up the drive of dying cypress.” There is the solidity of what was witnessed in the afternoon – but it is processed in a later moment of porous boundaries and elegiac memories. The title refers to flowers – but the reference locks in only after the reader has registered the word in its other sense. Soniat will dare such blatant transferences because the world she presents is always on edge.

The poem ends like this:

I needed mystery more than a mother. What I could not have comes to lie down beside me – blue pillow I rock with under the moon.

Deep muscular affliction, sundown. Slow dissolve of the road I rushed down to get past understanding there was only so much to make of space, and her brief landing.

Often, poets who “need mystery” find ways of enticing it into their way of speaking. When this occurs, the narrative impulse with its dependence on the structure of past time gives way to a more speculative moment of uttering. They don’t say they need mystery, they enact it. This technique implies a powerful talent for competing against power. But in Soniat’s poetry, the narrative persists because of the adult’s understanding that mystery (itself a revelation) is not granted absolutely. What “I could not have” is both there and not there. Soniat has an unmistakable genius for gathering disparate and seemingly ungraspable experiences into her poems while maintaining an intimately modest tone that implies a suspicion of willfulness, especially her own.

Often, poets who “need mystery” find ways of enticing it into their way of speaking. When this occurs, the narrative impulse with its dependence on the structure of past time gives way to a more speculative moment of uttering. They don’t say they need mystery, they enact it. This technique implies a powerful talent for competing against power. But in Soniat’s poetry, the narrative persists because of the adult’s understanding that mystery (itself a revelation) is not granted absolutely. What “I could not have” is both there and not there. Soniat has an unmistakable genius for gathering disparate and seemingly ungraspable experiences into her poems while maintaining an intimately modest tone that implies a suspicion of willfulness, especially her own.

Even so, as in the poem “Velocity” which speaks of the collapse of a levee, there are “No two ways of looking at it once the big winds are here.” Many of these poems stare directly at and remark on violence and death. The prose poem “Circle Singing” begins with a video of a woman in stiletto heels stomping a guinea pig to death and ends with devotional singing at church, “the day, for a song, turned darkly musical.” In this sense, there is only one way of looking at things, but it almost always involves looking at two things. This may be why her poems on wartime or political violence are not as resonant; they demand less from the reader and may seem merely worried.

In this collection, Soniat uses the longer prose line adeptly, often incorporating a leap of some sort within a sentence. Then, a ringing fragment. Soniat is a poet not so much devoted to undeniability as arrested by it. If the heaviness of life causes inertia, then her poems have no pretense of lightness. Rather, they suggest an assembled composure gathering momentum away from a voiceless, even stunned position.

RADIANCE

Bernadette walked from the kitchen singing “Hold On,” that song with a rising refrain. Her voice strong, she looked at us in turn: the woman with a bullet lodged in her head, one with the daughter dead a year, another whose unexplained anger flew loose daily. And me, the visitor trying to come home again.

Song filled the room by the pond, scarlet scarf on Bernadette’s head damp with sweat. Then that ringing, and how I knew to head for shade by the water. Your voice from a marriage ago. I fingered the phone cord like something umbilical as it filled with all the clues to mourning – every word a hot match in my ear. The cancer cells, the toxins. Doctors had made a mortal chemistry of your body, and you were ready to leave, radiant as the undeclared dead.

Artesian pool at my fingertips, clouds spring-gray and blowing overhead. And only moments before we had been speaking of our bodies. One friend wanted to keep each organ far past the end; another laughed at her corpse on a pallet at the harvesting center. And there you were, alive with death eating at you on the other end of the line.

How does the poet speak in a way that suggests a certain knowledge without reflecting credit on her/himself? Fear of the latter may discourage investigations of the former. But not once one has mastered and dispensed with such fears. Then there is the actuality of the thing. Soniat speaks radiantly – but as one of the “undeclared dead.” Not dead yet, in fact quite alive. But not able to deceive herself into solace. In fact, the pleasure is discovered in staring down the various toxins – and noting temporary stabilities where they appear.

How does the poet speak in a way that suggests a certain knowledge without reflecting credit on her/himself? Fear of the latter may discourage investigations of the former. But not once one has mastered and dispensed with such fears. Then there is the actuality of the thing. Soniat speaks radiantly – but as one of the “undeclared dead.” Not dead yet, in fact quite alive. But not able to deceive herself into solace. In fact, the pleasure is discovered in staring down the various toxins – and noting temporary stabilities where they appear.

In the book’s final poem, “World Drift,” the speaker observes freighters, stationary offshore. She writes, “One ship centered on the imperceptible curve of the sea. / I hold my finger up to reckon how truly things stay in place.” And the last lines: “A lighthouse spins the emptiness out – brilliance that makes / the waves look partial, and all this ocean manageable.” A Boat A Raft A Bridge is one continuous effort of manageability, a containment of both illusion (the finger held up to the eye) and the grief of loss. It is a sophisticated, empathic and candid vision of a world.

[Published by Dream Horse Press on August 15, 2012. 92 pages, &17.95 paperback original]

Re A Bridge

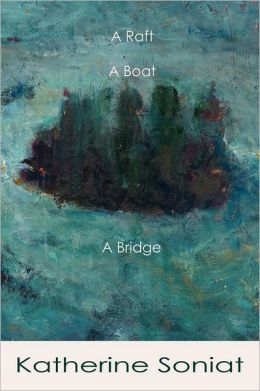

Thank you very much for that review. Her novel sounds marvellous. I shall chase it up. I’m no Freudian (laughs), but I happened to be re-reading some Freud today, viz. his stuff on the fort-da. The excitement and the fear mixed with the object. How we objectify by absence and replacement. (Where, I ask, is the succor there?) But of la Soniat’s book cover…probably the most beautiful design that I’ve seen for years. And who says you can’t tell a book by its cover?