The Wall Street Journal recently published Joseph Rago’s op-ed piece on Priya Venkatesan, a lecturer in English composition at Dartmouth who has “threatened to sue her students because, she claims, their ‘anti-intellectualism’ violated her civil rights … She maintains that some of her students were so unreceptive of ‘French narrative theory’ that it amounted to a hostile working environment … ‘They’d argue with your ideas.’ This caused ‘subversiveness.’” She reached her breaking point while lecturing on ecofeminism; when one student took issue, Venkatesan told the classroom that their behavior amounted to “ ‘fascist demagoguery.’ Then, after consulting a physician about ‘intellectual distress,’ she cancelled classes for a week.” Litigation is pending. In the meantime, Venkatesan has taken her show to Northwestern.

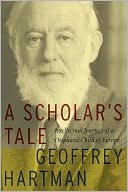

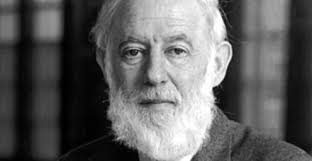

This article appeared during my reading of Geoffrey Hartman’s memoir A Scholar’s Tale, a book that tracks down the dangers of fashionable dogmatism in literary criticism, but has a larger, inspirational impulse: to envision a totality of lit-crit through his own remarkable embrace. The pathetic Dartmouth episode is, of course, an extreme and rare situation, at least regarding the litigation. But it raises the usual questions about the way literature is taught at the university, Hartman’s main topic.

This article appeared during my reading of Geoffrey Hartman’s memoir A Scholar’s Tale, a book that tracks down the dangers of fashionable dogmatism in literary criticism, but has a larger, inspirational impulse: to envision a totality of lit-crit through his own remarkable embrace. The pathetic Dartmouth episode is, of course, an extreme and rare situation, at least regarding the litigation. But it raises the usual questions about the way literature is taught at the university, Hartman’s main topic.

Hartman’s own opinions are firm – such as regarding the power of literature (independent from critical rendition) and the primacy of close reading over the more strident or complicated strains of criticism – even while he defends and incorporates the thinking of former Yale colleagues such as Paul de Man and the visiting Jacques Derrida. (“Many thought I was practicing deconstruction without a license.”) A Scholar’s Tale is not only an intellectual memoir but an impressive act of integration, a generous perspective on five decades of literary culture wars and academic camaraderie.

“What haunts a memoir that does not have the excuse of a significant personal conversion, revelation, exculpation, is the nexus of the life and the work,” he writes. “I strive to discover that link even if it proves to be reductive.” As depicted here, Hartman’s life is his work, and the haunting nexus is not discovered as much as visited, the way one keeps a caring eye on an aging mentor. The book’s subtitle, “Intellectual Journey of a Displaced Child of Europe,” speaks to the source of Hartman’s assimilative impulses. In March 1939, he was evacuated from Frankfurt on a Kindertransport and resettled in England. His mother had already fled to America; his grandmother died in the camp at Terezin. Nevertheless, discontinuity made Hartman an offer his temperament couldn’t refuse: the opportunity to repair, an instinctive last resort. He says, “Change has its own consistency”:

“As a child in England, I invented a ritual that already indicated the need to overcome damage from a traumatic separation by a counter separation. Suiting action to words, I would say to myself, regularly and compulsively: I will take three steps, one, two, three, and – everything is new and happy. Because, later, the moment of finding my mother was also that of losing her again – the years of separation and having become a young adult made it difficult to identify with the stranger meeting me at the dock [in New York] in 1945.”

“As a child in England, I invented a ritual that already indicated the need to overcome damage from a traumatic separation by a counter separation. Suiting action to words, I would say to myself, regularly and compulsively: I will take three steps, one, two, three, and – everything is new and happy. Because, later, the moment of finding my mother was also that of losing her again – the years of separation and having become a young adult made it difficult to identify with the stranger meeting me at the dock [in New York] in 1945.”

As a result of the breakage of his earliest bonds, “I have never thought of anyone in so personal a way as a role model. I did not wish to follow or have a following … Yet here and there I did catch a glimpse of someone in our profession I would have liked to be closer to.” The self-image accumulating in A Scholar’s Tale isn’t that of a loner but of one who stands alone among others close by. It’s a persona perfectly suited to tell this story of mediation. His career as a teacher and literary critic is shaped by dual impulses. First, to maintain continuity with a disrupted past. Second, to admit to the renewing power of change. On the one hand, family and culture had been destroyed. On the other, postmodernist criticism (incursions into philosophy) then sought to deconstruct what remained of experience and signification. “The objective of study has shifted from literature as a relatively independent, inner-directed system toward its potential and often stymied contribution to social justice,” he notes. “Our historical experience and political disenchantment had reached the point where every artistic treasure, every cultural trophy, was tainted by being associated with the victors and the official history they sponsored.” This stance toward “official” culture resonates with Hartman who prefers “instances of eccentric interpretation.” But he also fears that criticism’s gains in complexity have resulted in deficits in accessibility. His hope is that “literary criticism’s rich, ungovernable variorum of interpretations … might restrain dogmatism” and “satisfy my need for community,” a republic of the arts. Consequently, his own books of criticism drew on the entire set of practices in the academy. “I rarely invoked the aid of specific social, economic, or large-scale political theories,” he recalls. “By stressing theory’s text-dependence I was seeking to acknowledge its hidden parochialism and residual dogmatic bent, yet also shielding it from accusations.”

A Scholar’s Tale is structured as a series of encounters with persuasive ideas, influential scholars, forceful personalities, and great literature. “My first and lasting experience of open nature was the English countryside during the very time I encountered Wordsworth,” he recalls early in his memoir. He returns intermittently to this primal scene. “In the absence of father and grandfather, indeed all family except a mother I had grown apart from after close to seven years of separation, I adopted myself out to words blowing in the wind.” In Wordsworth (with Keats, one of his lifelong preferences) he discovered the “archaic structures of sensibility underlying religion’s visionary concepts.” Yet when the Structuralists and their followers came along and kicked the stool out from under collective “underlying” archetypes, Hartman found a place for them among the “eccentric” interpretations. He rejected the conservative claims that the “more strenuous form of interpretation,” with its complications and “issues of representation,” is antihumanistic.

A Scholar’s Tale is structured as a series of encounters with persuasive ideas, influential scholars, forceful personalities, and great literature. “My first and lasting experience of open nature was the English countryside during the very time I encountered Wordsworth,” he recalls early in his memoir. He returns intermittently to this primal scene. “In the absence of father and grandfather, indeed all family except a mother I had grown apart from after close to seven years of separation, I adopted myself out to words blowing in the wind.” In Wordsworth (with Keats, one of his lifelong preferences) he discovered the “archaic structures of sensibility underlying religion’s visionary concepts.” Yet when the Structuralists and their followers came along and kicked the stool out from under collective “underlying” archetypes, Hartman found a place for them among the “eccentric” interpretations. He rejected the conservative claims that the “more strenuous form of interpretation,” with its complications and “issues of representation,” is antihumanistic.

In an earlier essay, “Understanding Criticism,” Hartman wrote, “Critical thinking requires heterogeneity. Like good scholarship it keeps in mind the peculiarity of strangeness of what is studied. By ‘keeping in mind’ I mean it does not make art stranger or less strange than it is.” In the memoir, he reiterates this notion when he writes, “When I do venture a largish generalization, I like to make sure it is a noncoercive emanation of delight in words and perennial forms.” The world of Instructor Venkatesan, sponsored by departments of English, is one where coercion of interpretation rules over delighted response, and the tyrant files for victim’s restitution. More generally, young writers making their way through the university and MFA training feel the pressure to accede to certain stylistic trends. This is why Geoffrey Hartman’s appreciative and forgiving assessment of his times is important to poets, writers, and scholars. It is an antidote (too late, too modest?) to critical excess, and a cheer for the sufficing strangeness of literature.

[Published by Fordham University Press on October 15, 2007, 160 pp., $24.95 hardback]