It is said, as if it were obvious, that James Salter has structured his eight books of prose fiction around spikes of erotic arousal. The adrenals pump to the waft of pheromones and the rest is anticipation – unless the reader, attending to Salter’s tone and rhythms, inverts things and senses that the stories are founded on an uncompromising confrontation with disillusionment, disappointment, and death.

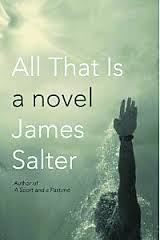

Salter is now 88. In his ninth and perhaps final novel, All That Is, a man’s entire life is chronicled. The amorous adventures are there as before, but the narrator’s tone tells us that the Book of Ecclesiastes got it right – the things of this world don’t add up in the end. The moment’s pleasure is paramount, and we are mastered by it and everything else that presses down on us.

Salter is now 88. In his ninth and perhaps final novel, All That Is, a man’s entire life is chronicled. The amorous adventures are there as before, but the narrator’s tone tells us that the Book of Ecclesiastes got it right – the things of this world don’t add up in the end. The moment’s pleasure is paramount, and we are mastered by it and everything else that presses down on us.

The adulthood of Philip Bowman, the main character, begins during the final year of World War II in the Pacific. After his naval discharge and a Harvard education, he finds work in a New York publishing house. Editing will become his lifelong profession in “a life superior to its tasks, with a view of history, architecture, and human behavior, including incandescent afternoons in Spain, the shutters closed, a blade of sun burning into the darkness.”

Before All That Is concludes somewhere around 1990, the unnamed narrator says of publishing, “The power of the novel in the nation’s culture had weakened. It had happened gradually. It was something everyone recognized and ignored. All went on exactly as before. That was the beauty of it. The glory had faded but fresh faces kept appearing, wanting to be part of it, to be in publishing which had retained a suggestion of elegance like a pair of beautiful, bone-shined shoes owned by a bankrupt man.”

That was the beauty of it … that the desire continues during the fading, even the finishing. If you remove these six words, the entire passage is altered and flattened. One reads Salter waiting for and continually finding such terse and essential lines that access a plunging depth, the quick and necessarily dismissed thought of a flyer. As devotees of Salter know, he flew fighter jets during the Korean war, experiences detailed in his memoir, Burning The Days (1997), and informing his debut novel, The Hunters, (1956).

That was the beauty of it … that the desire continues during the fading, even the finishing. If you remove these six words, the entire passage is altered and flattened. One reads Salter waiting for and continually finding such terse and essential lines that access a plunging depth, the quick and necessarily dismissed thought of a flyer. As devotees of Salter know, he flew fighter jets during the Korean war, experiences detailed in his memoir, Burning The Days (1997), and informing his debut novel, The Hunters, (1956).

As in his signature novel, A Sport and a Pastime (1967), the lives and psyches of Salter’s characters are organized around the erotic attractions of others and the satisfactions of reciprocal regard. All That Is tracks Bowman’s relationships through an early, brief, post-war marriage, then on to affairs with women encountered during travels or in New York with whom he lives for periods in America and Europe. Nothing sticks.

Candidly piercing what precedes it, a swiftly acute Salter-esque sentence almost always gets at a rising emotion or premonition in a character’s mind – not analyzed but pointed at, like something happening in the street. One of Bowman’s women is Enid Armour, born in South Africa, married, part of the coterie around an English publisher. She and Bowman invest in a racing greyhound that wins several contests in its first tries. The narrator says, “He won twice more. It began to have meaning … Bowman flew over for it when he was to run at White City, the great London track that was near the theatre district and had some glamour. He felt heady with Enid. They were a racing couple.” It began to have meaning … They were a racing couple … are sentences that barely convey specific information and yet imply much more than they say – mounting excitement, accumulating density of significance – thin phrases that simultaneously emit the sound of their ephemerality.

The novel follows Bowman but takes brief excursions to cover many other characters tangential to his life – his former mother-in-law, the family tragedy faced by a co-worker, the serial marriages of a Swedish publisher, the sudden reappearance of a wartime buddy, and so forth. The perspective is broad and dry. Bowman himself doesn’t utter a unique remark from beginning to end. In fact, dialogue throughout is determinedly ordinary. The narrator is the nexus, a little weary sounding as if the story is all too familiar to him and the urgency to tell it has diminished – but this was life, and has to be related according to what it actually was like. The novel is inhabited by an implacable sense of fate. Bowman regards Enid, through the speaker:

The novel follows Bowman but takes brief excursions to cover many other characters tangential to his life – his former mother-in-law, the family tragedy faced by a co-worker, the serial marriages of a Swedish publisher, the sudden reappearance of a wartime buddy, and so forth. The perspective is broad and dry. Bowman himself doesn’t utter a unique remark from beginning to end. In fact, dialogue throughout is determinedly ordinary. The narrator is the nexus, a little weary sounding as if the story is all too familiar to him and the urgency to tell it has diminished – but this was life, and has to be related according to what it actually was like. The novel is inhabited by an implacable sense of fate. Bowman regards Enid, through the speaker:

“There were times when she left to go on an errand, to the pharmacy or the consulate – she never bothered to explain why she’d gone to the consulate – and he suddenly felt with a certainty that in fact she was really leaving, that he would go back to the hotel and her bags would be gone, the clerk at the desk would know nothing. He would run in the street looking for her, the blondness of her hair in the crowd. The truth is, with some women you are never sure.”

It’s ridiculous to insist that Salter’s prose yield more philosophical insight or that Bowman enunciate his fears or specify what compels him to behave as he does. Reviewers making these complaints are also upset with the idea that Salter would arrive at the end of his career and suggest that this is all there is. Vivian Gornick in Book Forum chastises Salter for failing to package “any appreciable development” of his oeuvre in All That Is, as if novel writing were some form of social enrichment program. (What really bothers Gornick, ever the homeroom monitor, is that “there isn’t a woman in the book whom Bowman doesn’t turn over and take from behind.”)

In his 1993 Paris Review interview with Edward Hirsch, Salter talked about “a right way to live and die” based on “the classical, the ancient, the cultural agreement that there are certain virtues and that these virtues are untarnishable.” Salter doesn’t say so, but one of those virtues may be the yielding to – or at least acknowledging — what feels mythic in our lives and psyches. Gornick may sneer at Salter’s fictional women, but he also insisted, “I’ve made an effort to nurture the feminine in myself. I don’t mean overtly, but in terms of response to things. I’m happy with my gender, but pure masculinity, which I’ve been exposed to a lot in life, is tedious and inadequate.”

In his 1993 Paris Review interview with Edward Hirsch, Salter talked about “a right way to live and die” based on “the classical, the ancient, the cultural agreement that there are certain virtues and that these virtues are untarnishable.” Salter doesn’t say so, but one of those virtues may be the yielding to – or at least acknowledging — what feels mythic in our lives and psyches. Gornick may sneer at Salter’s fictional women, but he also insisted, “I’ve made an effort to nurture the feminine in myself. I don’t mean overtly, but in terms of response to things. I’m happy with my gender, but pure masculinity, which I’ve been exposed to a lot in life, is tedious and inadequate.”

There’s a delicious moment towards the end when Bowman attends a lecture by Susan Sontag (who was a fan of Salter’s work). A friend named Claire asks Bowman what he thought of the lecture:

”She’s a figure from the Old Testament,” he said.

”She’s such a powerful person. You just feel it.”

”All powerful women cause anxiety,” he said.

”Do you really think so?”

”It’s not a question of what you think. It’s what anybody thinks.”

”You do?”

”Men do,” he said.

She was a little dismayed. It sounded chauvinistic.

If, as stated by his novel’s narrator, “the power of the novel” has weakened during Salter’s lifetime, the reasons may include the demand for tendentiousness and explanation in fiction, corruptions of unearned knowingness, desperation for resolution, a preference for familiar padded-out blandness over the telling phrase, and a communal tin ear for the mythopoetic.

Like Bowman, neither Salter nor his novel settle for “some late, sentimental compromise.” For those who find the ending of All That Is dispiriting, Salter provides an unconsolingly apt perspective. As he remarked in the interview, “Well, life is an ordeal, isn’t it?”

[Published by A. A. Knopf on April 2, 2013. 290 pages, $26.95 hardcover]

On The Tin Ear

I first came across Mr Salter’s work years ago in “Solo Faces”, at about the same time I was committing myself seriously to rock-climbing. Don’t know about flying F-86 Sabres, but the quality of ordeal and the stoicism you mention is pretty much what I know the climbing experience to be. Exhilarating. Tedious. Repeat. Odd that Salter hasn’t yet gotten the wider recognition he deserves; I hope this novel swings the rope back in his direction. Man’s a star. Posthumous must feel awful.