In his latest book of essays, Angels & Saints, Eliot Weinberger, the prolific American essayist, editor and translator, immerses readers in the often absurd theological minutiae on Christian angels and Catholic saints. The former appear “less than two hundred times in the Bible, usually in passing.” Yet from these fleeting references, a rich mythology has been extrapolated and expanded upon by such revered Christian scholars as Saint Augustine, Thomas Aquinas and Increase Mathers. Their discussions are complex, contradictory, and surprisingly tedious. Do Angels have corporeal form or are they “an ever movable intellectual substance”? If they have no corporeal form, hence no tongue, how do they communicate? If they do have corporeal form, what shape does that form take? How do they inhabit space and time? What is the nature of their relationship to God and men? What is the angelic hierarchy, i.e. – their relationship to each other? Although the information is almost clinical, his hypotheses and conclusions are enlivened through stylistic switchbacks and flourishes:

“The fourth named angel is Uriel, who is frequent in the apocryphal books … but is not in the Bible. He is sometimes an archangel, sometimes a seraph, sometime the cherub who guards Eden, sometimes the Angel of Death in the seven plagues of Egypt, sometimes the angel who wrestled with Jacob, sometimes the messenger who warned Noah of the coming flood, sometimes the angel who excoriated Moses for neglecting to circumcise his son Gershom or the angel who rescued John the Baptist from Herod’s massacre of the innocents, sometimes a pitiless exacter of repentance, sometimes the one who taught humankind Kabbalah and the art of alchemy.”

“The fourth named angel is Uriel, who is frequent in the apocryphal books … but is not in the Bible. He is sometimes an archangel, sometimes a seraph, sometime the cherub who guards Eden, sometimes the Angel of Death in the seven plagues of Egypt, sometimes the angel who wrestled with Jacob, sometimes the messenger who warned Noah of the coming flood, sometimes the angel who excoriated Moses for neglecting to circumcise his son Gershom or the angel who rescued John the Baptist from Herod’s massacre of the innocents, sometimes a pitiless exacter of repentance, sometimes the one who taught humankind Kabbalah and the art of alchemy.”

Fortunately, Weinberger appears to be less interested in the content of their ideas than in the rhythms their words suggest to him. His writing, which jumps around within the boundaries of his subject, plays to his readers’ fractured sense of focus — though this probably has more to do with the current culture syncing to his personal process than a decision to cater to shrinking attention spans. Part George Perec, part Beat poet, Weinberger generates prose that offers a unique cadence, somehow combining his own lively sensibility with the much less lyrical and more institutional language of religious exegeses. The influence of Beat writers like Ginsberg, Kerouac and Burroughs is easy to spot. But the fingerprints of all of Weinberger’s heroes (not just the Beats, but traces of writers like Tom Robbins, Edward Abbey and Borges) have left smudges:

“… A particularly thorny question was whether Adam had a guardian angel before the Fall, while he was still in paradise, when presumably he wouldn’t need one (Aquinas said he did: Adam himself was in a state of innocence within, but was threatened by the snares of demons without.) Unfortunately, it was generally agreed that every person also has been assigned an evil angel by Satan, one who inspires thoughts and acts of wickedness. Individuals live torn between the two angels. Luther and the Protestants tended to be preoccupied with the evil ones.”

“… A particularly thorny question was whether Adam had a guardian angel before the Fall, while he was still in paradise, when presumably he wouldn’t need one (Aquinas said he did: Adam himself was in a state of innocence within, but was threatened by the snares of demons without.) Unfortunately, it was generally agreed that every person also has been assigned an evil angel by Satan, one who inspires thoughts and acts of wickedness. Individuals live torn between the two angels. Luther and the Protestants tended to be preoccupied with the evil ones.”

In the final pages of Part I. Angels — Angels & Saints is divided into three main parts, reminiscent of a medieval altarpiece or triptych — the names of angels and their spheres of influence are arranged on the page like an e.e. cummings’ poem. A few personal favorites from among the fragments: “Balberith, who notarizes pacts made with the devil”; “Maktiel, who rules over trees”; and “Tubiel, who returns small birds to their owners.”

Weinberger employs an arch tone, and his prose accelerates as he warms to his topic. He’s not averse to occasionally inserting himself in an aside; he was Borges’ English translator. But one can’t help but sense that the implicit joke running through the text — O how humans love to over-complicate! or in the words of Shakespeare, “Lord, what fools these mortals be!” – is unkindly made. The reader is invited to laugh along, but while we may be in on the joke, there is no doubting it is one made at someone’s expense.

II. Saints presents the lives of the saints in a more traditionally structured way, but the choices of who is included are telling. In all, Weinberger recounts anecdotes on the lives of some 142 saints (a small cross-section of sainthood — the Catholic church had canonized 10,000 at last count), sometimes over several pages and other times in a single sentence. He allows the absurdities of the miracles recognized by the church to speak for themselves, without exaggerating or embellishing, and the episodes he recounts from a saint’s hagiography easily lend themselves to religious pantomime or straight farce. There is the saint who swallows the Christ child’s foreskin, only to feel “the little skin on her tongue with sweetness as before, and again she swallowed it. And this happened to her about a hundred times.” Or Magdalena of the Cross, who performs multiple miracles, is courted by royalty, experiences an immaculate conception and a virgin birth, is made the abbess of an incredibly wealthy convent (in fairness, her miracles generated much of that wealth) only to reveal after 40 years that she has not been visited by an angel as she claimed, but knowingly and happily fornicated with a devil named Balban.

II. Saints presents the lives of the saints in a more traditionally structured way, but the choices of who is included are telling. In all, Weinberger recounts anecdotes on the lives of some 142 saints (a small cross-section of sainthood — the Catholic church had canonized 10,000 at last count), sometimes over several pages and other times in a single sentence. He allows the absurdities of the miracles recognized by the church to speak for themselves, without exaggerating or embellishing, and the episodes he recounts from a saint’s hagiography easily lend themselves to religious pantomime or straight farce. There is the saint who swallows the Christ child’s foreskin, only to feel “the little skin on her tongue with sweetness as before, and again she swallowed it. And this happened to her about a hundred times.” Or Magdalena of the Cross, who performs multiple miracles, is courted by royalty, experiences an immaculate conception and a virgin birth, is made the abbess of an incredibly wealthy convent (in fairness, her miracles generated much of that wealth) only to reveal after 40 years that she has not been visited by an angel as she claimed, but knowingly and happily fornicated with a devil named Balban.

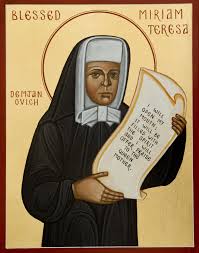

Some of the saints are not formally recognized by the Catholic church, but still have their adherents. Others are better known, like St. Christopher, though the story told here is probably not the familiar version. Frederick of Regensburg chopped the monastery firewood and, we assume, simply led a good life. Therese of the Infant Jesus and of the Holy Face had an entire religious-politico-media complex built around her story, complete with books and popular images of her holding the baby Jesus or as the face of the Virgin Mary offered for sale. Weinberger has collected men and women from every part of the globe, from all walks of life and up through modern times. Their miracles show varying degrees of impressiveness: Teresa Demjanovich was a 26-year old virgin who wished to become a nun. She died in 1927 of appendicitis in a hospital in Newark, New Jersey. Her hagiography is included among Brief Lives.

Some of the saints are not formally recognized by the Catholic church, but still have their adherents. Others are better known, like St. Christopher, though the story told here is probably not the familiar version. Frederick of Regensburg chopped the monastery firewood and, we assume, simply led a good life. Therese of the Infant Jesus and of the Holy Face had an entire religious-politico-media complex built around her story, complete with books and popular images of her holding the baby Jesus or as the face of the Virgin Mary offered for sale. Weinberger has collected men and women from every part of the globe, from all walks of life and up through modern times. Their miracles show varying degrees of impressiveness: Teresa Demjanovich was a 26-year old virgin who wished to become a nun. She died in 1927 of appendicitis in a hospital in Newark, New Jersey. Her hagiography is included among Brief Lives.

Part III. The Afterlife is, for all intents and purposes, the punchline. It’s a good one and I won’t ruin it.

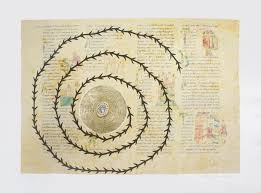

There’s a fourth and final section which doesn’t get a Roman numeral. A Guide to the Illustrations is written by the medieval scholar Mary Wellesley and explains the beautiful illustrations which appear throughout the book: a series of illuminated grid poems created by an 18-century Benedictine monk named Hrabanus Maurus. These poems – Wellesley compares them to word search puzzles — are perfect companions to the convoluted debates over what often amounts to semantic and theological minutiae which Weinberger is so taken with. Mary Wellesley’s examination injects an academic note into the conversation. But she, too, is in on the joke. Imploring us, “Dear reader – stay with me – we have only just begun” at the end of a particularly math-heavy paragraph. If this all seems overly erudite, at one level it is. But at another, it is all exceptionally beautiful and absorbing.

There’s a fourth and final section which doesn’t get a Roman numeral. A Guide to the Illustrations is written by the medieval scholar Mary Wellesley and explains the beautiful illustrations which appear throughout the book: a series of illuminated grid poems created by an 18-century Benedictine monk named Hrabanus Maurus. These poems – Wellesley compares them to word search puzzles — are perfect companions to the convoluted debates over what often amounts to semantic and theological minutiae which Weinberger is so taken with. Mary Wellesley’s examination injects an academic note into the conversation. But she, too, is in on the joke. Imploring us, “Dear reader – stay with me – we have only just begun” at the end of a particularly math-heavy paragraph. If this all seems overly erudite, at one level it is. But at another, it is all exceptionally beautiful and absorbing.

In a sense, Angels & Saints, with its avalanche of facts and tweet-sized bytes of information on angels, the lives of saints presented as flash-fiction and a Wikipedia entry on medieval grid poems, is a comfortable space for contemporary readers. Weinberger successfully manages the interconnecting pieces of information and pulls off a seamless integration of visual images and text. The reader’s journey is a lot like going down an Internet rabbit hole of research. The slickness of tone, reminding us that this author is also a prize-winning political columnist who wrote piercingly about the 9/11 and the Iraq War, somehow helps to lessen the dissonance between an arcane subject and a modern presentation. But that dissonance is, itself, fascinating. Weinberger’s project has its flaws, chief among them his willingness to sacrifice substance for style. But Angels & Saints also provides an intriguing glimpse at how the essay is evolving – the possibilities suggested by the ubiquity of social media and the Internet — in the 21st century.

[Published by New Directions on September 1, 2020, 160 pages, $26.95 hardcover]