E = mc². Einstein’s equation, arguably the 20th century’s most famous, posited an original way to perceive energy, one that still syncs beautifully with data streamed from the Hubble and Webb telescopes. In last year’s Transformer, the evolutionary biochemist Nick Lane bore down on the Krebs cycle, a metabolic pathway by which cells consume food (such as glucose) and then discharge energy — the very thing we need to breathe, or (put another way) not die. Meanwhile, pop-culture enthusiasts like my teenagers can recite Yoda’s discourse on the Force: “Its energy surrounds us and binds us. Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter. You must feel the Force around you. Here, between you, me, the tree, the rock — everywhere, yes. Even between the land and the ship.”

Energy, then, is an obsession of physicists and biologists and filmmakers alike. It pervades the universe, from supermassive black holes to quarks. And yet as historian Jackson Lears asserts in his intellectually rich Animal Spirits, the roles of energy are rooted in older debates about vitality — what it is, how it shapes our world, when and why it leaves us. He traces the arc of American vitalist thought, from (per the subtitle) camp meeting to Wall Street. But does he stuff too much beneath the umbrella of his title?

Energy, then, is an obsession of physicists and biologists and filmmakers alike. It pervades the universe, from supermassive black holes to quarks. And yet as historian Jackson Lears asserts in his intellectually rich Animal Spirits, the roles of energy are rooted in older debates about vitality — what it is, how it shapes our world, when and why it leaves us. He traces the arc of American vitalist thought, from (per the subtitle) camp meeting to Wall Street. But does he stuff too much beneath the umbrella of his title?

The book’s Introduction cites a common primordial myth among indigenous peoples: “In the beginning … all was in constant flux, until a trail of cosmic accidents led to tension and eventual separation between women and men, humans and animals, gods and mortals. Yet even after this fragmentation, earthly creatures continued to inhabit an animated universe, where rocks, trees, plants, and animals were all ensouled with a mysterious force or spirit,” referred to as manitou or mana by anthropologists. Lears’ goal is to pin down the biography of a single complex idea, resurrected by John Maynard Keynes’ realization “that the key to investor confidence is the presence of animal spirits — ‘the spontaneous urge to action,’” also known as life force, libido, and élan vital. As Lears notes, “Capital from the Keynesian view, could be conceived as a shimmering magnetic force at the core of economic life. Like the mana of indigenous peoples, it was a product of the human imagination that took on a life of its own … the world of finance capital, despite its apparatus of quantified rationality, is governed at bottom by fantasy and fear.”

He scrutinizes vitality throughout the prisms of our institutions: religious, cultural, financial. He launches his own inquiry in the British Restoration, the age of Adam Smith and Daniel Defoe, when “popular philosophers of a vitalist bent aimed to capture this sense of free-floating energy and possibility. They imagined animal spirits prowling the wider world in various aliases and disguises: animal magnetism, mesmeric fluid, electrical fluid, electromagnetic fluid, electricity.” We think of Defoe, of course, as the author of Robinson Crusoe, but his capitalist insights inform his legacy. “From Defoe’s view, banks had a responsibility to oil the workings of commerce by extending credit to visionary entrepreneurs (as twenty-first century business idealogues have learned to call them),” Lears writes. “The fluid metaphors seemed inescapable: the oil of credit promoted other forms of liquidity. In recognizing the centrality of credit to the emerging capitalist economy, Defoe had hit upon the most pervasive and elusive power in the early modern world. For him, in effect, credit was to the body economic as animal spirits were to the individual body: a mysterious but essential vital force, an evanescent liquid evaporating into thin air.”

Lears then shifts to the early years of our republic, forged at a moment when the Enlightenment’s verities were pivoting to the drumbeats and tumbrels of revolution — Romanticism by another name. American vitality was distinct from its European cousins, though, simmering in ivied colleges and meeting houses, bristling with Puritanical fervor. Lears places Timothy Dwight, grandson of the theologian Jonathan Edwards and president of Yale University, at the center of a burgeoning creed: “Part of his appeal was nationalistic as well as religious. To Dwight the Second Great Awakening was a sign that the Kingdom of God on Earth was beginning here, now, in America. The fledgling United States would become the Redeemer Nation of the world. The thought had crossed the minds of other prominent Protestants, including Edwards. But a belief that had earlier been fitful and indirect became explicit and triumphant in Dwight. He was a founding father of American exceptionalism, the faith that America was divinely ordained to remake the world in its own image. Dwight’s ideas became foundational to a new, enlightened orthodoxy that lasted for decades, sustaining a hegemonic ethos with scant sympathy for animal spirits or vitalist philosophy.”

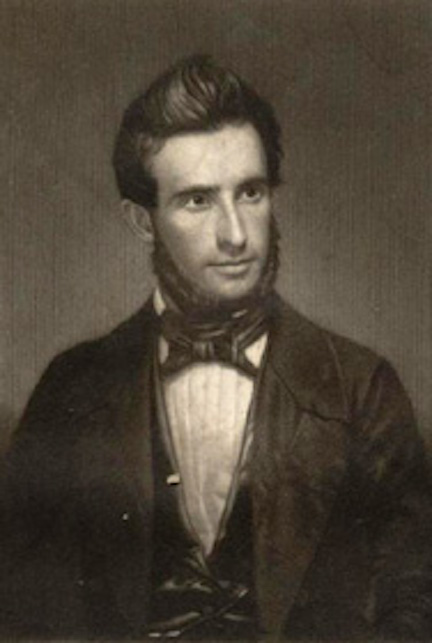

[left: Andrew Jackson Davis] In the Victorian era, the concept of a “pulsating cosmos” was popular; the public took its cues from advances in transportation, among them trains and steam-powered ships. There were hucksters galore. Mesmerists, usually male, would attempt to soothe or cure a client, usually female, resulting in an exchange that allowed him to stroke her face and torso: predation as therapy. Animal Spirits serves up a delectable rogues’ gallery. Andrew Jackson Davis, a handsome autodidact known as the “Poughkeepsie Seer,” claimed the gift of clairvoyance and healing. He preached a gospel of energy that weirdly echoed the themes, even the rhythmic language, of Emerson and Whitman. (Lears suggests that Davis may have had ulterior motives: deflecting accusations of bigamy and infidelity.) In Davis’s own words we hear the stirrings of an authentic American voice, vast and sweeping, the cadences of multitudes and declarations of selfhood. E pluribus unum. “His vision ranged far beyond Poughkeepsie,” Lears observes, and then aligns a Davis quote with one from Whitman: “’I saw the many and various forms of the forests, fields, and hills, all filled with life and vitality of different hues and degrees of refinement.’ At such moments he inhabited an ‘I’ unbounded by space and time, like Whitman’s in ‘Song of Myself’: ‘My ties and ballast leave me, my elbows rest in sea-gaps, I skirt sierras, my palms cover continents, I am afoot with my vision.’ Both men courted feelings of boundlessness.”

[left: Andrew Jackson Davis] In the Victorian era, the concept of a “pulsating cosmos” was popular; the public took its cues from advances in transportation, among them trains and steam-powered ships. There were hucksters galore. Mesmerists, usually male, would attempt to soothe or cure a client, usually female, resulting in an exchange that allowed him to stroke her face and torso: predation as therapy. Animal Spirits serves up a delectable rogues’ gallery. Andrew Jackson Davis, a handsome autodidact known as the “Poughkeepsie Seer,” claimed the gift of clairvoyance and healing. He preached a gospel of energy that weirdly echoed the themes, even the rhythmic language, of Emerson and Whitman. (Lears suggests that Davis may have had ulterior motives: deflecting accusations of bigamy and infidelity.) In Davis’s own words we hear the stirrings of an authentic American voice, vast and sweeping, the cadences of multitudes and declarations of selfhood. E pluribus unum. “His vision ranged far beyond Poughkeepsie,” Lears observes, and then aligns a Davis quote with one from Whitman: “’I saw the many and various forms of the forests, fields, and hills, all filled with life and vitality of different hues and degrees of refinement.’ At such moments he inhabited an ‘I’ unbounded by space and time, like Whitman’s in ‘Song of Myself’: ‘My ties and ballast leave me, my elbows rest in sea-gaps, I skirt sierras, my palms cover continents, I am afoot with my vision.’ Both men courted feelings of boundlessness.”

In Animal Spirits we also meet more venerable figures — Herman Melville, Henry Ward Beecher, William James, Theodore Roosevelt — all of whom put their stamp on the vitalist tradition. Curiously, Lears steers clear of the greatest explosion of energy in U.S. history: the Civil War. He notes in passing how the War drained both North and South of inner reserves (and hundreds of thousands of men) even as it unleashed fresh ideas and creativity with the overturn of slavery. That elision must mean something.

Lears delves into the exponential growth of American capitalism, cycles of booms and panics that he ties to the ascendancy — and scapegoating — of the restlessness and high-stakes curiosity fundamental to the American character. Speculation, bank rushes, fortunes made and lost in the blink of an eye — Lears meticulously details the social inequities and reforms that accompanied the Gilded Age and into the modern era, with a focus on race and sex, how old orders broke down and new configurations rose from their ashes. He showcases the people who chipped away at conventionality, as in his portrait of the wealthy, freethinking Mabel Dodge Luhan. “A key figure in the revitalized feminist movements of the 1910s, Luhan merged social and sexual radicalism,” he writes. “Her chief inspiration was the birth control advocate Margaret Sanger, who appeared often at Luhan’s Greenwich Village salon, mesmerizing the other participants by evoking the unexplored possibilities of female sexual experience. Luhan recalled these episodes in her autobiography: ‘For Margaret Sanger to attempt what she did at that time seems to me now like another attempt to release energy in the atom, and who knows but perhaps the best describes what she tried to do,’ Luhan wrote.”

[right: Mabel Dodge Luhan] Radical change as atom-splitting: Luhan’s reminiscence of Sanger encapsulates the scope of Lears’ project. He seeks evidence of animal spirits across disciplines as vast and disparate as physics and theology, commerce and art; he mostly succeeds in linking them all to his conceit. In its closing pages, Animal Spirits sleuths through breakthroughs in science and technology. The book went to press before last month’s headlines about the Webb telescope’s startling discoveries beyond our own galaxy. Recent data proves that the warp and woof of space time radiates from volcanic mergers of supermassive black holes, crimped by energy spewed from black holes that formed less than a billion years after the Big Bang. As one report opined, “We are all bobbing in a sea of ripples in space time, reverberating through the fabric of the universe … probably the distant thunder of countless collisions between supermassive black holes.”

[right: Mabel Dodge Luhan] Radical change as atom-splitting: Luhan’s reminiscence of Sanger encapsulates the scope of Lears’ project. He seeks evidence of animal spirits across disciplines as vast and disparate as physics and theology, commerce and art; he mostly succeeds in linking them all to his conceit. In its closing pages, Animal Spirits sleuths through breakthroughs in science and technology. The book went to press before last month’s headlines about the Webb telescope’s startling discoveries beyond our own galaxy. Recent data proves that the warp and woof of space time radiates from volcanic mergers of supermassive black holes, crimped by energy spewed from black holes that formed less than a billion years after the Big Bang. As one report opined, “We are all bobbing in a sea of ripples in space time, reverberating through the fabric of the universe … probably the distant thunder of countless collisions between supermassive black holes.”

Energy defines us, our speck of rock among the roiling structures that compose the observable universe. Animal Spirits comes full-circle to its opening. Defoe, Whitman, and Andrew Jackson Davis were all prophets, foretelling the essence of life itself — and Lears’ book is a magnificent, if dense, contribution to how we understand ourselves.

[Published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux on June 20, 2023, 464 pages $32.00 hardcover]