A long epigraph by Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) opens the way to Sarah Vap’s jaunty essay-in-passing on poetry’s language, pedagogies, commonplaces and confusions, End of the sentimental journey: a mystery poem (Noemi Press). Here is a fragment:

“ … at the very moment when the soul is about to organize its wealth, its discoveries, its revelation, at that unconscious moment when the thing is about to emanate, a higher and evil will attacks the soul like vitriol, attacks the word-and-image mass, attacks the mass of the feeling and leaves me panting as at the very door of life.”

“ … at the very moment when the soul is about to organize its wealth, its discoveries, its revelation, at that unconscious moment when the thing is about to emanate, a higher and evil will attacks the soul like vitriol, attacks the word-and-image mass, attacks the mass of the feeling and leaves me panting as at the very door of life.”

One of Artaud’s successors, Pierre-Albert Jourdan (1924-1981), wrote similarly in his own notebook, “The inner disaster is the only resource.” Like Artaud, he was not referring to an emotional or mental breakdown, but pointing to a more fundamental fecklessness evading conventional language. Yet he also insisted “the path is still open” toward latent potentials, even as the increasingly disastrous events of the century were mocking them. The inner disaster is never original to oneself.

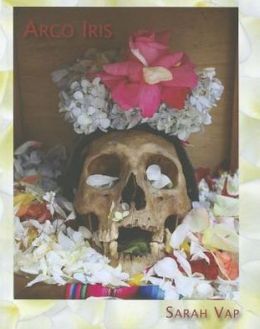

These quotations seem even more relevant to Vap’s poem/travelogue Arco Iris (Saturnalia Books), also recently published. Here, Vap conjures a yearning yet contained voice narrating a journey to South America with a companion named “Lover.”

If an incapability, prior to or separate from persona, precludes expression that would name things and experiences as never before, then the primary purpose of writing may be to redeem. If so, one’s style incorporates an implied ethics with a bias for the mind’s most unpersonal locutions. In Vap’s case, the ethics are often explicit if stated on a slant – they act as both compass and baggage.

Travel

The continent spread apart then the continent condensed around us. Like the continent, we made an effort to remember. Memory, we thought at first, was something like pathos — and at the infinite remove –

But memory was weight. Memory was the heavy mirror of history was shadow falling at your face – falling at your face.

Here, travel enacts an effort of detachment that would reattach — traveling light, avoiding the graven ruts of language and memory. Sometimes the detachment seems impossible, except in uttering the wish – but then, a slight effect, a certain sensation of slightness, makes it so. If you are heading to Tayrona from the States, you are an eco-tourist, bundled with your values and burdened with your culture’s history. Stricken and startled, Vap’s poems are entrancements of disparity, balancing precariously between specificity of phrase and the predeterminations of speaking. The work is rife with struggle toned down by the coolness of observation, an immediate remarking on what-just-happened, a mistrust of “an interior shriveled / by the same old trap, cleverly set.”

Here, travel enacts an effort of detachment that would reattach — traveling light, avoiding the graven ruts of language and memory. Sometimes the detachment seems impossible, except in uttering the wish – but then, a slight effect, a certain sensation of slightness, makes it so. If you are heading to Tayrona from the States, you are an eco-tourist, bundled with your values and burdened with your culture’s history. Stricken and startled, Vap’s poems are entrancements of disparity, balancing precariously between specificity of phrase and the predeterminations of speaking. The work is rife with struggle toned down by the coolness of observation, an immediate remarking on what-just-happened, a mistrust of “an interior shriveled / by the same old trap, cleverly set.”

Currency

Finally we begin to touch the people who live here. The tips of our fingers touch, or my fingers at their palms or theirs at mine. Or our arms when they hand something to me that I have asked for. When I hand something back to them.

Now I imagine how we might touch. I find more ways I want even more ways to ouch – whoever you are who thinks that I don’t want you – here. Take this money. Give me something beautiful you have made.

It is not that the poems are impersonal. It is simply that Vap will not rely on tone to elevate her person’s anxieties into elegant gestures. Besides, her concerns tend to the transpersonal – gender, race, power. In her poem-essay, she writes, “the contemporary vocabulary of intimacy has failed me!” Her tone aptly specifies a demand to be taken seriously for reasons other than the erecting of a magnetic persona. She is unafraid of making statements – they penetrate swiftly, before we can weigh or discount them.

We think when will the light come. We think

how turn off the light.

We fuck and contemplate down the river –

the river profound the river echoing with television.

Our fucking in the hammock hidden by our blanket just like everyone else’s fucking just inches

from ours is hidden by their blankets and we think

there is something inside of us.

We are slamming are digging at something

that is inside of everyone that wants to hide from a screaming light.

As a travel journal, Arco Iris opens to the presences and places on its tour. Many of the pieces revel in a dissolve into elemental description. Meanwhile, Vap’s inner disaster, with its impairments of the white North American tourist, may risk monotony and hyperbole. But she knows when and how to modulate such urges, allowing a certain narrowness to pinch the narrative. In “Travel” (there are six poems so titled) she self-skewers the privileged, globalized tourist: “I need a cup of coffee why’s it so hard to find coffee it’s fucking grown here where’s the fucking coffee.” Vap’s depictions of disorientation emit a familiar strangeness – such that the tropical exoticism of her subject reflects on a more generic out-of-placeness, as in these lines from “Spring –”:

As a travel journal, Arco Iris opens to the presences and places on its tour. Many of the pieces revel in a dissolve into elemental description. Meanwhile, Vap’s inner disaster, with its impairments of the white North American tourist, may risk monotony and hyperbole. But she knows when and how to modulate such urges, allowing a certain narrowness to pinch the narrative. In “Travel” (there are six poems so titled) she self-skewers the privileged, globalized tourist: “I need a cup of coffee why’s it so hard to find coffee it’s fucking grown here where’s the fucking coffee.” Vap’s depictions of disorientation emit a familiar strangeness – such that the tropical exoticism of her subject reflects on a more generic out-of-placeness, as in these lines from “Spring –”:

Sometimes we hate what we do altogether so then we try to become transparent. Then we try to become opaque. Then we try to be quiet and to fold or to spread or to spill ourselves out but there’s nowhere — …

There may not be much humor in Arco Iris, but there is much shredding comedy in Vap’s poem-essay, End of the sentimental journey. It begins with a querying and dismissal of claims that certain poems are “difficult.” She writes:

There may not be much humor in Arco Iris, but there is much shredding comedy in Vap’s poem-essay, End of the sentimental journey. It begins with a querying and dismissal of claims that certain poems are “difficult.” She writes:

Sometimes, when someone says that a poem is difficult, what I feel is: you want that poem to intuit your most private fantasies and just play along!

Sometimes, when I hear someone say that a poem is difficult, I think: But maybe that poem didn’t want to date you in the first place. Maybe it’s exceedingly happily married, thanks, and would never even consider it.

Maybe, if you were the last person on earth, that poem would hump a rock.

Naturally, this is actually serious business for Vap. There are antagonisms to identify; she knows she must write in opposition, but to what? After the kidding, she announces that difficulty might really be about “who can say and think what and how they can say it and think it.” For Vap, much of that thinking and saying is entangled in gendering. A little further on, she names “Catholicism and Political Correctness” as strict traditions from which she has departed. But Vap has been pursuing a Ph.D. in creative writing, an institutional marination in hot orthodoxies. End of the sentimental journey teaches best as an outburst of equivocations and a tweaking of noses. It is a spirited and instructive performance, inflating incorrect gestures to an audience for whom incorrectness is de rigeur. If you are enrolled in a writing program, best to acquire a copy. Vap says out loud what her colleagues are thinking.

She says, “I’m against any one tenor of language becoming so beloved, so performed, so privileged, that it becomes – like the holy language of Catholicism of my childhood and the correct language of political correctness of my young adulthood – ineffectual.” She quotes Marjorie Perloff’s insistence that poetry “is not the expression or externalization of inner feelings; it is, more accurately, the critique of that expression … a critique of everyday life.” But Arco Iris suggests that she may be wary of sanctioned devaluations of style, attitude, and individual presence. I think I believe her when she says, “More likely, I’m against all unreasonable obedience.” And, “Sometimes, I want a poem that I don’t even like.”

She says, “I’m against any one tenor of language becoming so beloved, so performed, so privileged, that it becomes – like the holy language of Catholicism of my childhood and the correct language of political correctness of my young adulthood – ineffectual.” She quotes Marjorie Perloff’s insistence that poetry “is not the expression or externalization of inner feelings; it is, more accurately, the critique of that expression … a critique of everyday life.” But Arco Iris suggests that she may be wary of sanctioned devaluations of style, attitude, and individual presence. I think I believe her when she says, “More likely, I’m against all unreasonable obedience.” And, “Sometimes, I want a poem that I don’t even like.”

About traditional expression, she writes, “Holy language and correct language, for me, were empty of my experiences. Empty of my private articulations. I felt monitored in mouth, and monitored in mind.” And, “While I honored and respected much of both traditions, I wavered between feeling, on the one hand, enraged at the internalized monitoring, and, on the other hand, feeling a rather extreme desire to get the language of either correctness just exactly right.”

What especially impresses me about Vap, aside from her irreverence and antics, is her adept exploitation of both current orthodoxies and personal experiences for inventive purposes, reinvigorating the language while offering a seat on the transport to the reader. As she says in her essay, “These moments of intimacy are why I read and write.” The “difficulties” of her work are marks of affection.

[Arco Iris. Published on October 15, 2012 by Saturnalia Books. 88 pages, $15.00, paperback. End of the sentimental journey. Published on April 16, 2013 by Noemi Press, 71 pages, $15.00, paperback]