Simeon Marsalis’ debut novel, As Lie Is To Grin, is told in the voice and writings of David, an African-American freshman at the University of Vermont in the fall of 2010. He makes an appointment to see a psychologist at school: “I felt like a boy in a man’s body. ‘I need help’ … I told her I hated everyone, hated this session, and hated her compliance, which did not abate until I was empty of thirty-six minutes of talk.” David is then referred to a Dr. Hume who prescribes Citalopram for depression. In between the two appointments, David types “Vermont medicine psychology tests” in his browser and discovers that the university had sponsored eugenics programs in the 1930s that resulted in 131 sterilizations of people diagnosed with Huntington’s chorea, then regarded as a mental illness. With an eye quick to detect traces of historical abuse, looming threats and pending offenses in the school’s architecture, David is nevertheless trying to find ways of becoming socialized with his world.

In As Lie Is To Grin, Marsalis shows no inclination to charm the reader or to encourage a facile identification with and empathy for his main character. He selects and sticks to an almost accentless narrative tone in keeping with David’s critical, fearful perspective and aloof demeanor. What saves David from merely persisting as a blandly aggrieved character is his uncertainty, the discomfiture of his youth, and the fact of his addressing us. There is a hidden appeal: to be heard in his disordered state. His intimacy must be earned because the reader is the only one in his world, other than David himself, who can gauge the troubled density of his experience.

In As Lie Is To Grin, Marsalis shows no inclination to charm the reader or to encourage a facile identification with and empathy for his main character. He selects and sticks to an almost accentless narrative tone in keeping with David’s critical, fearful perspective and aloof demeanor. What saves David from merely persisting as a blandly aggrieved character is his uncertainty, the discomfiture of his youth, and the fact of his addressing us. There is a hidden appeal: to be heard in his disordered state. His intimacy must be earned because the reader is the only one in his world, other than David himself, who can gauge the troubled density of his experience.

The narrative soon takes up events that occurred previously. David met Melody at a carnival in 2007, told her he lives in Harlem (he does not), and carried on a relationship with her. He never quite indicates why he is drawn to her. She is an aspiring artist who lives in Midtown; they meet at her apartment. Soon her father, Rick, appears:

“While we walked out of the park, I imagined running in the opposite direction. I tried to keep calm, telling myself, ‘These urges are very human,’ but Rick and Melody continued to talk to each other, pronouncing all of their words correctly, and their sarcasm became cynical – I could not stop thinking I did not like either her or her father. After we finished eating, I stayed over. Richard locked the door to his room. ‘He said you could stay.’ And I smiled, because I did not have to get back on the train to Long Island tonight and cut writing class tomorrow. In the moonlight, I was confronted by her glowing whiteness.”

Simmering in the background is David’s agitated relationship with an emotionally abusive mother, and the shadow of an absent father. Generating anxiety from a mere handful of facts, Marsalis avoids analysis and summations on David’s part and relies almost solely on the moment’s urgencies. “We kissed each other,” David says. “She was licking and biting my lip, and I had the desire to push her, or yell, or show her how angry these small affections made me, but I closed my eyes, smiled once or twice, and walked to the A train.” The novel’s few plot contrivances are tooled, perhaps conveniently, as armature for the novel’s racial weight rather than to lead towards nuance. But it doesn’t matter – the draw of the voice rests on a struggling self-critique interwoven with passing observations that keep one alert for trouble that lies ahead.

David is trying to write a novel having been inspired by Jean Toomer’s Cane — and he is failing in an indistinct way insofar as he wishes to contravene the standards of commercial fiction. As for Marsalis himself, As Lie Is To Grin may not be an avant-garde project, but it earnestly captures the waywardness of a young mind and its tentative attempts to gain a foothold in situations that come embedded with danger signals. Marsalis has allowed himself to build a fiction that could slip off the page into pieces – all in the service of illuminating the muffled traumas faced by a young man like David. Even so, Marsalis never asks us to privilege either David or his novel for its timeliness. His deep generosity is comprised in allowing the reader to make an assessment based on his main character’s testimony.

David is trying to write a novel having been inspired by Jean Toomer’s Cane — and he is failing in an indistinct way insofar as he wishes to contravene the standards of commercial fiction. As for Marsalis himself, As Lie Is To Grin may not be an avant-garde project, but it earnestly captures the waywardness of a young mind and its tentative attempts to gain a foothold in situations that come embedded with danger signals. Marsalis has allowed himself to build a fiction that could slip off the page into pieces – all in the service of illuminating the muffled traumas faced by a young man like David. Even so, Marsalis never asks us to privilege either David or his novel for its timeliness. His deep generosity is comprised in allowing the reader to make an assessment based on his main character’s testimony.

Towards the end of the novel, David says of his fellow students, “Looking at my peers, I could not discern individual faces, just white faces that were a combination of faces I had seen before. And I continued passing by the campus buildings, with their European façades, I noticed that every single person grinned at me. Smiled, mocking, as if I were on the receiving end of some long and deliberate joke.” It was here that I was reminded of Floyd Skloot’s memoir In The Shadow of Memory. Skloot grew up in an extremely stressed family environment and became interested in research on how the brain re-wires itself for over-response to stress. “When trauma occurs in the body,” he wrote, “it activates certain immune-responses in the brain. The loop connecting stress-related chemicals and immune-system chemicals is tight one.” Over and over, neurochemicals flood the brain when stress occurs – until the brain itself has been irrevocably hurt. I don’t suggest that we psychoanalyze Marsalis’ David. I simply mean to say: Marsalis gave me the chance to hear the spoken sound of a certain stress – and it shook me up.

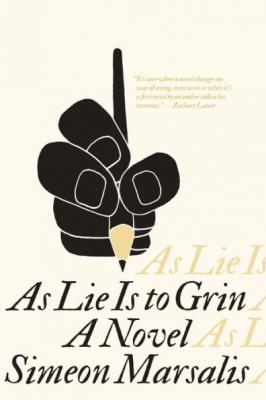

[Published by Catapult on October 10, 2017. 151 pages, $16.95 paperback]