What does it mean to think and live aesthetically in the post-industrial, globalized world? There are long traditions of self-fashioning on cultural, familial, historical, spiritual or religious, economic and other grounds. There is an equally long tradition of fashioning one’s life as a work of art and an object of adoration. But the former modes seem more distinct and easier to qualify through their overpowering influence and staying power. They persist primarily as solutions to problems.

Styling one’s life on aesthetic grounds is something else entirely and usually intended as a response to the dominance of the other modes. The fashion is an advertisement for autonomy, a flourish that spreads a cape over its antagonists as if it could snuff them out with a swish. At the same time, life-as-art may usurp political, historical, cultural and religious content into itself, reconstituting those materials into an alternative narrative. Its attitude affirms (even disappointment); its gesture reveals (even disappearance). Resisting with verve, life-as-art aspires to irresistibility. Its speech is generally more attuned to pitch than tone, but it isn’t tone-deaf to nuance.

Styling one’s life on aesthetic grounds is something else entirely and usually intended as a response to the dominance of the other modes. The fashion is an advertisement for autonomy, a flourish that spreads a cape over its antagonists as if it could snuff them out with a swish. At the same time, life-as-art may usurp political, historical, cultural and religious content into itself, reconstituting those materials into an alternative narrative. Its attitude affirms (even disappointment); its gesture reveals (even disappearance). Resisting with verve, life-as-art aspires to irresistibility. Its speech is generally more attuned to pitch than tone, but it isn’t tone-deaf to nuance.

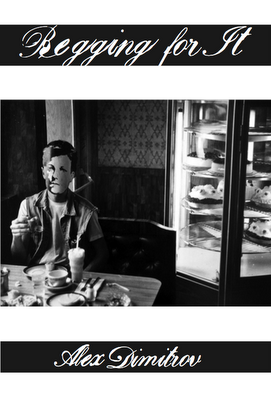

Alex Dimitrov’s first collection of poems, Begging For It, comprises a determined vision of a youthful aesthetic life. But it doesn’t exist for the purpose of peddling the preferences or behaviors of Alex Dimitrov. The young man on the page is a young man on the stage. Self-presentation and -cancellation occur simultaneously. But where one might expect the postmodernist to allude to things only to elude them, Dimitrov’s scenarios don’t dissolve. The world is worshiped. The text, a beautiful thing in the world with a life-as-art speaking inside it, makes disquietude its subject, not its technique.

As one reads, the boundary between audience and stagecraft may dissolve in the immediacy of the act and the bold intimacy of address. This is when one senses the generosity in the poems – they welcome you into their freedom. You are regarded as an irresistible listener, the one who approaches, the one who may be approached. In “This Is A Personal Poem” he writes, “My self’s self is thinking about itself. / Trying to sell its self a new self. // Don’t worry, reader. / I’m not trying to fool you with language. // I have eyes to do that with.”

BEGGING FOR IT

He crosses the dead avenue,

walks toward you, and loosens his ring

the way you imagine your father once did

on some night he still hasn’t returned from.

Men you’ve lived with

and men you live on.

Whose scent will your knuckles keep?

His jaw clenches because your blood mixes sweetly

with the flower under his tongue,

the marquee’s cheap glint,

each cab that passes and won’t stop.

It’s the night before Easter.

You do not forget it.

How the body becomes a cage you can’t feel your way out of –

how God rips through the skin

of every man you know,

on a quiet evening,

in a city already done for, like this one.

Insofar as one listens to the voice here, one lives with it. Insofar as one apprehends the voice, one lives on it. This, at least, is the poem’s desire. For those who don’t immediately acquiesce, there’s an undisguised didactic fillip implying This is what you are like, too. A precocious poem about “every man.”

The poem “Minor Miracles” ends with these lines: “Gentle boy, remove the knife — / but sweetly, sweetly. // Burn the bed / in which I no longer wait for you.” They and other similar phrases call back to the poems of António Botto who was, according to Fernando Pessoa in 1922, “the only Portuguese, of those known to be writing today, to whom the label of aesthete may be applied without question.” Botto simply assumed that loving beauty libidinously is what we do (or are capable of). He knew, of course, that to do so is to deviate, but deviation in art wasn’t his aim, just his manner. His Anglophone editor, Josiah Blackmore, says, “The poet’s attitude is relaxed and insouciant. The languorous, provocative posture suggests self-possession, an almost defiant gesture of unencumbered, self-aware indulgence in bodily pleasure.” Pessoa named Botto a great aesthete because he pursued the Hellenic ideal of making art for the purpose of making the world more beautiful. The pursuit is depicted in the poems – the adored body is exalted for its beauty. Botto writes, “In your last letter / You called me decadent. / How funny! / Your letter / Made me laugh.”

The poem “Minor Miracles” ends with these lines: “Gentle boy, remove the knife — / but sweetly, sweetly. // Burn the bed / in which I no longer wait for you.” They and other similar phrases call back to the poems of António Botto who was, according to Fernando Pessoa in 1922, “the only Portuguese, of those known to be writing today, to whom the label of aesthete may be applied without question.” Botto simply assumed that loving beauty libidinously is what we do (or are capable of). He knew, of course, that to do so is to deviate, but deviation in art wasn’t his aim, just his manner. His Anglophone editor, Josiah Blackmore, says, “The poet’s attitude is relaxed and insouciant. The languorous, provocative posture suggests self-possession, an almost defiant gesture of unencumbered, self-aware indulgence in bodily pleasure.” Pessoa named Botto a great aesthete because he pursued the Hellenic ideal of making art for the purpose of making the world more beautiful. The pursuit is depicted in the poems – the adored body is exalted for its beauty. Botto writes, “In your last letter / You called me decadent. / How funny! / Your letter / Made me laugh.”

Dimitrov broadens Botto’s vision of the aesthetic life to include childhood memories, urban melancholia, political critique, speculative drift and provisional identity. Tonally, he relies on a weary knowingness. Even the rudiments of aestheticism begin to show wear and tear: “obsession / no longer turns into pleasure, // though we yield to each terror / and ask to be taken gently” (“21st Century Lover”). If there is repetition, it derives from a confirmed focus. But it isn’t a narrow view. Dimitrov achieves a great deal with an anecdote and associative leaps:

TO THE THIRSTY I WILL GIVE WATER

Yesterday morning while I read Montaigne

a man drove his car into the Gowanus canal.

I have never seen a greater monster or miracle

than myself, Montaigne wrote in the late 16th century.

It was a bright day.

The sun forgave no one.

Not even the firefighter who first saw

the car taken by the water while he was praying,

lighting a cigarette, remembering his lover’s face –

what was he doing, what did he think of before diving in?

It is not death, it is dying

that alarms me, Montaigne tells us.

Because he swallowed enough black water during the rescue

the firefighter was given two Hepatitis B shots afterward.

The man who lost his car was given his life back.

We were given Montaigne’s heart

which is preserved in the parish church named after him

in the southwest of France.

We were given more than we can drown.

The aesthete asks to be shaken in a way that validates the faith he places in the supremacy of beauty. The man in the poem is depicted as begging for the arrival of this proof – but the beauty in many of his poems is the outspoken sound of the begging itself, the attested admonishment and attractive blandishment. These are the final lines of “We Are A Natural Wonder”:

The aesthete asks to be shaken in a way that validates the faith he places in the supremacy of beauty. The man in the poem is depicted as begging for the arrival of this proof – but the beauty in many of his poems is the outspoken sound of the begging itself, the attested admonishment and attractive blandishment. These are the final lines of “We Are A Natural Wonder”:

I’m looking for one secret about people

no matter the season or city or how dark their eyes are.

Arrivals, departures, few words, less wonder.

If it is rain we are least like, let us be rain.

[Published March 12, 2013. 83 pages, $15.95 paperback original]

The Songs of António Botto, selected and edited by Josiah Blackmore and translated by Fernando Pessoa, was published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2010. $17.95 paperback.

most obvious omission

I’m wondering how anyone can review such a book without mentioning the word ‘gay’ or putting these poems in the context of queer poetics. Mainstreaming Alex Dimitrov’s poetry is not only a disservice but a misreading.

So I’ll say this, I didn’t

So I’ll say this, I didn’t even think about affiliation etc etc and the man honors the work in many ways. What’s the mainstream anyway? Exists?

No Polemics Zone

It’s probably unfair not to mention a waste of time to expect Ron Slate to write polemically about anything. In the first part of this essay, he tells you that the poet is doing something unconventional with identity and that he isn’t writing to promote specific “behavior.” I think this may be an indirect reference to the thing Kris wants spelled out. But it is just not what interests Ron about Dimitrov’s work. He supplies ample evidence of and comment on what does interest him. Let others take up the task of placing the work in a polemical framework. I thank Ron for looking intently at the work itself. And I just bought a copy of the book as a result. DC, Webster University, St Louis, MO

In Dimitrov’s own words

‘I remember a few years ago I was at the Lambda Literary Awards and Edward Albee was receiving a lifetime achievement award, and he got up there and talked about how he is not a gay writer but a writer who happens to be gay and everyone criticized him, because I suppose they wanted to hear some didactic, sweeping reaffirmation of how being specifically same-sex oriented has informed his work or is seen in his work. That’s too easy. And boring. I understood his resistance to entering that space where the work is suddenly entirely illuminated by his sexuality. That resistance is in itself queer. And more interesting and complicated.’

It’s worth reading the entire interview. Inhabiting the margins, of course, is not limited merely to those who are gay.

link: http://www.lambdaliterary.org/interviews/03/29/in-conversation-mark-wunderlich-alex-dimitrov/

On Begging

so used to live on a street here in shanghai greeted by beggars whenever i went anywhere convinced they had my number they knew my face and daily schedule here in the worlds second largest economy your professional beggar will lay hands on you now i dont think controversy or argument or aggression was really the point of it lord to be confined by our need to understand to make sense of a larger pattern send it off into disputacious territory do we stand still for the polemic to arrive or zag into the woods you cant argue the draw of it but in the end it always wants you to follow it