In the years 1906 and 1907, Picasso painted “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” Matisse his “Blue Nude,” Klimt the “The Kiss,” and Kandinsky “Riding Couple.” Braque exhibited his “Viaduc à l’Estaque” at the Salon d’Autumne. Meanwhile in Worpswede in northern Germany, a 30-year old painter named Paula Modersohn-Becker fled to Paris on a February night without giving notice to her husband, telling only Rainer Maria Rilke and his wife, Clara Westhoff, Paula’s closest friend. In a spare room in Paris, she began painting feverishly.

Standing before her mirror, she painted the world’s first nude female self-portrait. As Diane Radycki writes in her biography of the artist, “At the threshold of modernism, Paula Modersohn-Becker risked everything in order to become ‘something.’ Who she became was a daring innovator of gender imagery – the first modern woman to challenge centuries of traditional representations of the female in art … Not only did she reconfigure the nude, but she also resituated still-life painting.”

Standing before her mirror, she painted the world’s first nude female self-portrait. As Diane Radycki writes in her biography of the artist, “At the threshold of modernism, Paula Modersohn-Becker risked everything in order to become ‘something.’ Who she became was a daring innovator of gender imagery – the first modern woman to challenge centuries of traditional representations of the female in art … Not only did she reconfigure the nude, but she also resituated still-life painting.”

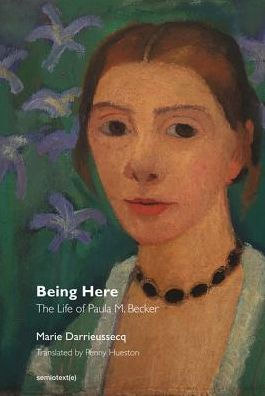

The French novelist Marie Darrieussecq, having taken Modersohn-Becker’s letters and diaries in hand, as well as those of the artist’s relatives and friends, has produced a tersely penetrating “life.” With a tone at once brisk and mordant, Darrieussecq incorporates the lively vibration of Paula’s aspirational attitude, a striving under the paternalistic shadows of father, husband, and art tradition. But also, there is the tint of desperation, anger, and disgust, the somber horror of Paula’s ambitions cut short, her early death.

In Paris, Paula had beckoned her husband, Otto Modersohn, a painter of sellable landscapes who recoiled from modernism. Their unconsummated marriage of five years (his anxieties had precluded sexual intercourse) now yielded a pregnancy. She returned to Worpswede, gave birth with great difficulty, and was treated as an invalid. She died suddenly on November 2, 1907 from a pulmonary embolism, probably from enforced bed rest of 18 days, uttering only “What a pity” as she collapsed. Darrieussecq calculates that although Paula portrays herself with a round belly in her Paris self-portrait, she was probably not pregnant at the time; Otto had not yet arrived. If this is the case, Paula envisioned her foreshortened future.

In Paris, Paula had beckoned her husband, Otto Modersohn, a painter of sellable landscapes who recoiled from modernism. Their unconsummated marriage of five years (his anxieties had precluded sexual intercourse) now yielded a pregnancy. She returned to Worpswede, gave birth with great difficulty, and was treated as an invalid. She died suddenly on November 2, 1907 from a pulmonary embolism, probably from enforced bed rest of 18 days, uttering only “What a pity” as she collapsed. Darrieussecq calculates that although Paula portrays herself with a round belly in her Paris self-portrait, she was probably not pregnant at the time; Otto had not yet arrived. If this is the case, Paula envisioned her foreshortened future.

The progression of her life, from her youth in Bremen and early art training in London to her days at the Worpswede art colony and the creative ferment in Paris, requires little commentary by Darrieussecq to establish its significance. The story is spare and episodic, preserving the sense of anticipation, the next challenge, the ensuing steps Paula must take. Darrieussecq speaks up briefly along the way, indicating the force of her deeply abiding interest in her subject:

What do we call her? Modersohn-Becker, the name of her future husband, also the name on the catalogues devoted to her work? Becker-Modersohn, ads in her museum in Bremer? Becker, her maiden (virgin) name, which the name of her father?

“The simple and honest name of Becker” is a common surname in Germany. Paula Becker is the name of a girl whose father was called Becker and who was given the first name of Paula.

Women do not have a surname. They have a first name. Their surname is ephemeral, a temporary loan, an unreliable indicator. They find their bearings elsewhere and this is what determines their affirmation in the world, their “being there,” their creative work, their signature. They invent themselves in a man’s world, by breaking and entering.

Paula’s only means in finding an accord with the world was through her art. At certain points, support came from her mother (an American boarder taken in to pay for Paula’s Berlin art school) and an uncle (funds to pay for her first visit to Paris in 1900, the tiny room, the tuition). But there is also Rilke, aide to Rodin in Paris and itinerant poet, who spends time with Paula intermittently and is generous to her. They talk for hours and share Rilke’s notion of Fromm — purity, as applied to one’s uncompromising pursuit of art. They inspire and elude each other. One year after her death, he publishes his poem “Requiem for a Friend.” Darrieussecq writes:

Paula’s only means in finding an accord with the world was through her art. At certain points, support came from her mother (an American boarder taken in to pay for Paula’s Berlin art school) and an uncle (funds to pay for her first visit to Paris in 1900, the tiny room, the tuition). But there is also Rilke, aide to Rodin in Paris and itinerant poet, who spends time with Paula intermittently and is generous to her. They talk for hours and share Rilke’s notion of Fromm — purity, as applied to one’s uncompromising pursuit of art. They inspire and elude each other. One year after her death, he publishes his poem “Requiem for a Friend.” Darrieussecq writes:

Paula, as seen by Rilke in her [Worpswede] studio, was “all beauty and slenderness, the new lily flowing … It was a long pathway, the end of which no one could see, in order for us to arrive at this timeless moment. We looked at each other, with a shiver of amazement, like two beings who suddenly find themselves before a door behind which there may be a god, already …I escaped, running over the moorlands.”

Rilke met her in Worpswede while she was trying to achieve a breakthrough in the period following her first visit to Paris. She had married Otto Modersohn immediately after the death of his first wife. “Marriage does not make one happier,” she wrote in her notebook. “It takes away the illusion that had sustained a deep belief in a kindred soul.”

Otto in his diary:

“A great gift for color – but unpainterly and harsh, particularly in her completed figures. She admires primitive pictures, which is very bad for her – she should be looking at artistic paintings. She wants to unite color and form – out of the question the way she does it … Women will not easily achieve something proper. Frau Rilke, for example, for her there is only one thing and its name is Rodin.

Her father, insisting that she take cooking lessons to please her husband’s palate, sent her off for two months to Berlin to master the art of fricassee. Finally, she had enough. She writes, “I think I am living very intensely in the present.” Darrieussecq writes:

She is having an affair with the sun: that is how she describes it to Clara just before their falling-out. Not the sun that divides, that shatters the image into shadows, but the sun that unites things: low on the horizon, heavy, contemplative, as if extinguished. That’s the sun she paints: no shadow, no effects. No added meaning. No innocence lost, no virginity defiled, no female saints sacrificed. Neither discretion nor false modesty. Neither Madonna nor whore. Here is a young girl: already these two words are excessive, loaded with Rilke-like reveries and with masculine poetry. These girls are saying: “Leave us alone!”

Darrieussecq’s Being Here Is Everything is truly a book for our moment, especially in the cautionary aspects of the story, the constriction of the female. But it is also a classic story about what it takes to make one’s most committed, liberated art. Paula Modersohn-Becker sold three paintings in her lifetime, one of which to Rilke. In 1911, the first of a series of articles about her in German art magazines began appearing. After World War I, her journals were published and widely read. Her work was exhibited regularly starting around 1920 until the Nazis arrived in 1934 and labeled her work “degenerate.” There was an American show at MOMA in 1931. Her paintings were variously categorized as post-Impressionist, modernistic, Cubist-influenced, Fauvist, and apocalyptic.

Darrieussecq’s Being Here Is Everything is truly a book for our moment, especially in the cautionary aspects of the story, the constriction of the female. But it is also a classic story about what it takes to make one’s most committed, liberated art. Paula Modersohn-Becker sold three paintings in her lifetime, one of which to Rilke. In 1911, the first of a series of articles about her in German art magazines began appearing. After World War I, her journals were published and widely read. Her work was exhibited regularly starting around 1920 until the Nazis arrived in 1934 and labeled her work “degenerate.” There was an American show at MOMA in 1931. Her paintings were variously categorized as post-Impressionist, modernistic, Cubist-influenced, Fauvist, and apocalyptic.

Here are the opening lines of Rilke’s “Requiem for a Friend” (1909):

And in the end you saw yourself like a fruit,

took off your clothes, carried

yourself to the mirror, let yourself in

all but your gaze; that remained large outside

and did not say: this is me; no, this is.

So without curiosity was your gaze in the end

and so unpossessive, of such true poverty,

that it no longer desired even you: holy.

[Published by Semiotext[e] on November 28, 2017. 160 pages, $17.95 paper]