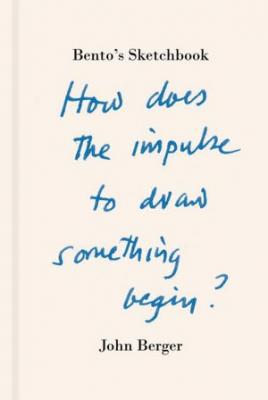

Starting with Ways of Seeing in 1972, John Berger has written out of wonderment about art making and expression. While most art historians and critics make discoveries and then engrave them into books, Berger’s creative essays give the sense of discovering as they proceed. In Bento’s Sketchbook, Berger returns to the subject of drawing and asks, “How does the impulse to draw something begin?”

If there are no entirely new insights in Bento’s Sketchbook, this is because Berger’s work over five decades has been based less on a progressive maturation of concepts and theses than on permanently abiding awe and compassion. “To draw is not only to measure and put down, it is also to receive,” he wrote in “A Professional Secret.” “When the intensity of looking reaches a certain degree, one becomes aware of an equally intense energy coming towards one, through the appearance of whatever it is one is scrutinizing.” In “Opening a Gate” he wrote, “The modern illusion concerning painting is that the artist is a creator. Rather he is a receiver. What seems like a creation is the act of giving form to what he has received … A likeness is something left behind invisibly … The image has to be full — not of resemblance but of searching.”

If there are no entirely new insights in Bento’s Sketchbook, this is because Berger’s work over five decades has been based less on a progressive maturation of concepts and theses than on permanently abiding awe and compassion. “To draw is not only to measure and put down, it is also to receive,” he wrote in “A Professional Secret.” “When the intensity of looking reaches a certain degree, one becomes aware of an equally intense energy coming towards one, through the appearance of whatever it is one is scrutinizing.” In “Opening a Gate” he wrote, “The modern illusion concerning painting is that the artist is a creator. Rather he is a receiver. What seems like a creation is the act of giving form to what he has received … A likeness is something left behind invisibly … The image has to be full — not of resemblance but of searching.”

Collegiate art history majors may be trained to respect the patriarchal standards of edifices like Kenneth Clark, but everyone intuitively grasps Berger’s critique when he states, “A lamb chop painted by Goya touches more pity than a massacre by Delacroix.”

Unlike Berger’s collections of essays, Bento’s Sketchbook is an extended meditation, wandering and peering, marked by slight turnings that open to vast spaces. It incorporates slices of reminiscence, commonplace book entries, descriptions of artworks and his responses to them, and travelogue. His own drawings are presented without commentary but are sometimes referred to in the text. The presiding spirit is “Bento” – Baruch Spinoza, the 17th-century Dutch-Jewish philosopher who was expelled from the Amsterdam Synagogue for his masterpiece Ethics. Spinoza then took the Christian name Benedict and also referred to himself as Bento, his Portuguese name. Berger’s narrative is interrupted by and blends with excerpts from the Ethics. Spinoza was known to have enjoyed sketching but there is no extant sketchbook. Berger’s book gestates into the former’s contemporary incarnation.

Unlike Berger’s collections of essays, Bento’s Sketchbook is an extended meditation, wandering and peering, marked by slight turnings that open to vast spaces. It incorporates slices of reminiscence, commonplace book entries, descriptions of artworks and his responses to them, and travelogue. His own drawings are presented without commentary but are sometimes referred to in the text. The presiding spirit is “Bento” – Baruch Spinoza, the 17th-century Dutch-Jewish philosopher who was expelled from the Amsterdam Synagogue for his masterpiece Ethics. Spinoza then took the Christian name Benedict and also referred to himself as Bento, his Portuguese name. Berger’s narrative is interrupted by and blends with excerpts from the Ethics. Spinoza was known to have enjoyed sketching but there is no extant sketchbook. Berger’s book gestates into the former’s contemporary incarnation.

Berger’s artist-hero makes no distinction between appearance and essence, yet is shaken separately by both. He says, “We who draw do so not only to make something visible to others, but also to accompany something invisible to its incalculable destination.” Spinoza argued that at its ontological basis, the universe is an integrated and infinite substance called God or Nature. His rabbis were enraged by his assertion that things aren’t ruled by a supernatural being with moral (human) attributes. In effect, Spinoza dared everyone to confront the substance of reality. Berger’s claims for art – and his combative political stance – are based on the continuing failure of human civilization to face up to what he has called “the struggle of living with Necessity, which is the enigma of existence … and which has always continued to sharpen the human spirit.” Necessity is what is there. History is the chronicle of what we have done with what is there, a story so damning that we flee from it.

Berger appears while observing a plum orchard, or swimming at the local municipal pool (which evokes the tragedies of Vietnam and Cambodia), or shopping at a big-box superstore (in which everyone is made to feel like a potential thief). In one section, the spry octogenarian describes his fascination with “a certain parallel between the act of piloting a bike and the act of drawing”:

Berger appears while observing a plum orchard, or swimming at the local municipal pool (which evokes the tragedies of Vietnam and Cambodia), or shopping at a big-box superstore (in which everyone is made to feel like a potential thief). In one section, the spry octogenarian describes his fascination with “a certain parallel between the act of piloting a bike and the act of drawing”:

“You pilot a bike with your eyes, with your wrists and with the leaning of your body. Your eyes are the most importunate of the three. The bike follows and veers towards whatever they are fixed on. It pursues your gaze, not your ideas. No four-wheeled vehicle driver can imagine this. If you look hard at an obstacle you want to avoid, there’s a grave risk that you’ll hit it. Look calmly at a way around it and the bike will take that path.”

After two Spinoza quotations and a little more bike talk, Berger leaps to the act of drawing, leaving the reader to feel out the connection:

After two Spinoza quotations and a little more bike talk, Berger leaps to the act of drawing, leaving the reader to feel out the connection:

“The challenge of drawing is to make visible on the paper not only discrete, recognizable things, but also to show how the extensive is one substance. And, being one substance, it harasses the act of drawing. If the lines of a drawing don’t convey this harassment the drawing remains a mere sign. The lines of a sign are uniform and regular: the lines of a drawing are harassed and tense. Somebody making a sign repeats an habitual gesture. Somebody making a drawing is alone in the infinitely extensive.”

The one who draws rides the drawing.

He spells out related implications for writers – and no one is more effective than Berger at placidly instilling a sense of ecstatic responsibility in the minds of receptive poets and storytellers. At mid-book, Berger takes up Anton Chekhov’s statement: “The role of the writer is to describe a situation so truthfully that the reader can no longer evade it.” He muses over the word “outcome”:

“Traditionally the term refers to how a story ends, to what finally happens to the protagonists. A tragic, happy or transcendent ending. Yet it can also refer to how the listener or reader or spectator leaves the story to continue their ongoing lives. Where does the story deposit those who have followed it, and in what frame of mind are they. The answer to this question may depend upon what the story has uncovered and revealed, or upon its moral imperative, if it has included one. But, according to my hunch, there’s another more interesting answer …

Throughout the story we become accustomed to the storyteller’s particular procedure of bestowing attention, and of then making a certain sense of what was at first glance chaotic. We begin to acquire his storytelling habits.”

As Mark Strand has said, the poem is always trying to persuade us: Be like me. Berger has spent a lifetime trying to decipher exactly what our art is asking us to be like, and unlike many other critics, he has emphasized and insisted on a severe moral outcome that also privileges eccentric expression. He prefers the unfinished where “there is never a single thread” and stories with forms imposed by partial answers.

Bento’s Sketchbook is held together by correspondences – and the image of a bicycle recurs in Berger’s story about a friend named Luca who lives in a Paris suburb. Luca rides a bicycle that is over sixty years old. He keeps a notebook, jotting remarks “about work which he has observed being well or carelessly done on the little houses or along the residential roads he passes by each day.” His parents left Mussolini’s Italy and made their living in France as a tailor and a dressmaker. Luca worked for Air France as a performance controller of aircraft, traveling the world to examine Boeings and Concordes. He worked meticulously. Now that his wife is hospitalized with Alzheimer’s, Luca calculates that he can fund her care for 1,095 days. This very ordinary yet moving story arrives at a typical Bergeresque passage: “How can destinies be named? They often have the regularity of geometric figures, but there are no nouns for them. Can a drawing replace a noun? I thought so this morning. Now I’m not so sure. I gave Luca the drawing, and the next day he framed it.”

Bento’s Sketchbook is held together by correspondences – and the image of a bicycle recurs in Berger’s story about a friend named Luca who lives in a Paris suburb. Luca rides a bicycle that is over sixty years old. He keeps a notebook, jotting remarks “about work which he has observed being well or carelessly done on the little houses or along the residential roads he passes by each day.” His parents left Mussolini’s Italy and made their living in France as a tailor and a dressmaker. Luca worked for Air France as a performance controller of aircraft, traveling the world to examine Boeings and Concordes. He worked meticulously. Now that his wife is hospitalized with Alzheimer’s, Luca calculates that he can fund her care for 1,095 days. This very ordinary yet moving story arrives at a typical Bergeresque passage: “How can destinies be named? They often have the regularity of geometric figures, but there are no nouns for them. Can a drawing replace a noun? I thought so this morning. Now I’m not so sure. I gave Luca the drawing, and the next day he framed it.”

In another section addressed to Arundhati Roy, Berger speaks out passionately about protest. (This is the man who gave half of his Booker Prize winnings to the Black Panthers.) “One protests in order to save the present moment, whatever the future holds … A protest is not principally a sacrifice made for some alternative, more just future; it is an inconsequential redemption of the present. The problem is how to live time and again with the adjective inconsequential.” Confronting the substance of the present is the writer’s or artist’s vocation and responsibility as well – and there we find the linkage not only to the political, but to the numinous.

In our culture, the art we make is virtually inconsequential, yet it often seems that everything depends on it. Berger writes that “any original political initiative has to start off as being clandestine” because of the “innate paranoia” of those holding power. So it follows that because of the innate resistance to creative expression even among the liberally educated, art will seem to emit a secret sound or present a masked countenance.

In our culture, the art we make is virtually inconsequential, yet it often seems that everything depends on it. Berger writes that “any original political initiative has to start off as being clandestine” because of the “innate paranoia” of those holding power. So it follows that because of the innate resistance to creative expression even among the liberally educated, art will seem to emit a secret sound or present a masked countenance.

Bento’s Sketchbook is also a book about autumnal desire. His manner of presenting characters is both simple and sensuous, and his touch is both light and unwavering. These characters have the same weight as the windfall plums he admires and gathers in the orchard. The summons to create is mysterious, and we answer it with our physical selves. Berger teaches that we are subject to the incoming sounds, rhythms and light of experience. This happens out of necessity and fundamental need. But also, we create in accordance with our unfathomable desires. The result: we conjure presences of things that are not there. The impulse to draw or to write begins here – where the tangible and the intangible “harass” each other.

Berger mentions his recent ten-year interest in the stories of Andrei Platanov (1899-1951). He draws a sketch of Platanov’s head from a photo. Later, he glues a railway ticket stub on the sketch since Platanov was a master of “the disturbance of distances.” We learn more about Platanov and his writing – especially regarding a story he wrote concerning a red Army soldier returning home after years in service. He breathes in the special smells of his own home and the scent of his wife’s hair – but he also recalls the smell of leaves in a forest and “unsettled life.” The story uncovers a hint about the “imaginative movement which prompts the impulse to draw” or to write:

“There is a symbiotic desire to get closer and closer, to enter the self of what is being drawn, and, simultaneously, there is the foreknowledge of immanent distance. Such drawings aspire to be both a secret rendezvous and an au revoir!.”

Many of Berger’s drawings are of flowers and plants. Irises are his favorites to draw. He says, “Irises are like prophesies: simultaneously astounding and calm.” This equally describes John Berger’s presence, tone and mode in Bento’s Sketchbook.

[Published by Pantheon on November 5, 2011. 162 pages, 61 drawings by Berger, $25.95 hardcover]

Berger’s passion

Your own comments on Berger are proof that this great writer can inspire with a profound ease. I encourage everyone to invest in the entire series of Berger titles. Most if not all are in print as paperbacks. Also, his novel G, which won the Booker Prize you mention, is a classic, as well as To the Wedding and his other fictions.