In his essay “Poetry and Pleasure,” Robert Pinsky writes that Walt Whitman worked via “the assumption that what is in him, if he can only follow its tides and creatures as faithfully as a naturalist, will be beautiful and interesting.” His confident largesse would empower him to fulfill the expectations he believed people held about the poet. He spelled it out in his 1855 preface to Leaves of Grass: “… they expect him to indicate the path between reality and their souls.”

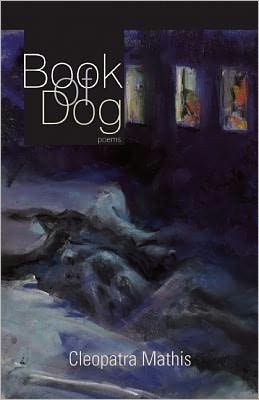

In Book of Dog, her sixth collection of poems, Cleopatra Mathis overtly tracks her reactions to actual tides and creatures but with a similar mission – to indicate a path towards accommodating oneself to loss. She dramatizes an education, but the by-products of education – knowledge, wisdom – aren’t easy to handle in poetry, and some readers quite justifiably feel uncomfortable with or even reject such offers.

In Book of Dog, her sixth collection of poems, Cleopatra Mathis overtly tracks her reactions to actual tides and creatures but with a similar mission – to indicate a path towards accommodating oneself to loss. She dramatizes an education, but the by-products of education – knowledge, wisdom – aren’t easy to handle in poetry, and some readers quite justifiably feel uncomfortable with or even reject such offers.

But Pinsky helps us with a qualification: ”The creation of interest through the most pleasurable ways of knowing: that is what poetry is.” The pleasures of Book of Dog come from the ways in which Mathis gambles: she bets on the figure of a woman emerging from divorce, an adept at discovering correspondences of her situation – of her status as a suddenly solitary being – in the ocean’s restlessness, the corpses of animals and insects, and the thoughtlessly stubborn regrowth of life. But one also hears unease, self-critique, disgust, and doubt.

All of these elements are her material. She is depicting, narrating a story. Certain sonic pleasures ensure that the telling won’t sound like an earnestly inert self-improvement project. What truly impresses here are the tug and pull between simplicities and hurdles — diction and syntax tamping down griefs that spring forward anyway. For me, what is “beautiful and interesting” in Book of Dog isn’t the earned clarity heard in what is spoken but rather the tidal tensions that make such clarity sound so desperate in the first place.

All of these elements are her material. She is depicting, narrating a story. Certain sonic pleasures ensure that the telling won’t sound like an earnestly inert self-improvement project. What truly impresses here are the tug and pull between simplicities and hurdles — diction and syntax tamping down griefs that spring forward anyway. For me, what is “beautiful and interesting” in Book of Dog isn’t the earned clarity heard in what is spoken but rather the tidal tensions that make such clarity sound so desperate in the first place.

And I haven’t yet mentioned the dogs. Book of Dog has three sections. In the first, “Canis,” the unresponsive man appears, on his way out. The speaker refers to herself here as “I,” there as “she” as in “she was like any other distraction to him.” But this isn’t what really preoccupies her anymore. In the second poem, she begins the book’s series of inquisitions:

ANTS WANT MY YELLOW MOTH

The one that came to me out of the sea, perfect

serrated edges of its six wings,

each seamless with tiny yellow feathers,

the two bright center ones with fake black eyes

pretending sight. Even drowned,

the wings held tight, a simple knot at the top

attaching them to the black worm of the body.

What fragile stitchery the tide held up,

carrying it in on a wave. I took it to my desk,

arranged it so as to see the colors as they dried,

the veins rising, shuddering with my breath.

But now, this any has found its way

under my immaculate shack and climbed the pilings,

through gaps in the floorboards to one leg

of my writing table, and up to that surface

plane of three cracked boards, where it scurries

to the moth: my creature.

Pulled from the sea with my own hands – mine, I think,

because I believe my very will can save it.

Book of Dog is ultimately a book about looking, and the desire attached to the looking, to understand, to obtain a higher perspective. But the difficulty of knowing what she is looking at is obscured by the vividness of the object itself. The clarity of phrase seems to strip away all impediments – this poem is mine, I think. Then the delusion is unveiled.

But here’s the gamble. The psychologist Adam Phillips writes, “In psychoanalysis there is always the risk that the wish for meaning will be usurped by the will to meaning” [italics mine]. Mathis is fearless when it comes to epiphanies – she doesn’t care if they’re unstylish these days. On the contrary, she dares herself to be willful, to depict the effort of trying to see by looking a second time. A poem made with her own hands, barely saved by (or despite) her very will, because it still wishes. Poems with a dead bird and a dead fox precede “Chipmunk in the Pool” where again she behaves “as if she can convince this thing to be saved.” These are primly coherent poems about the fecklessness of the will to make things cohere. One begins to sense the danger: language is all she has. Will it suffice?

But here’s the gamble. The psychologist Adam Phillips writes, “In psychoanalysis there is always the risk that the wish for meaning will be usurped by the will to meaning” [italics mine]. Mathis is fearless when it comes to epiphanies – she doesn’t care if they’re unstylish these days. On the contrary, she dares herself to be willful, to depict the effort of trying to see by looking a second time. A poem made with her own hands, barely saved by (or despite) her very will, because it still wishes. Poems with a dead bird and a dead fox precede “Chipmunk in the Pool” where again she behaves “as if she can convince this thing to be saved.” These are primly coherent poems about the fecklessness of the will to make things cohere. One begins to sense the danger: language is all she has. Will it suffice?

In the poems, she has the dogs. The book’s second section is the thirteen-part poem “Book of Dog.” “The plain language of the dogs” based on need, dependably straightforward yet (depending on the dog) capable of coyness or sneakiness – this language helps to negotiate the space between the human and the wild. In this section, the peering gives way to familiarity, which in the poem’s final segment leads to another of Mathis’ moments of reflection:

On the cape, in the changing season,

under that noise

of sloshing against pilings, the push-in-

push-away, close then farther out;

underneath the gulls’ bark, the desolate

ambient sound the dog understands –

the moving unstoppable current,

every complication reduced to repetition

as if to beat in some kind of lesson:

not urgency

in the water’s fist

clenching and releasing, but being —

without need or purpose, and in my body all this time

the answering sweep of valves

opening and closing; just as the little

terrier, brimful of nerve and trembling,

alone, perched there, sentinel on the deck’s edge,

has been trying all along to teach.

Fortunately, Book of Dog doesn’t end here, mainly because the woman is not a dog. Her manner of speaking may seem highly controlled, but she is alternately “clenching and releasing” per her own psyche and character. As Adam Phillips also says, “That which the subject wishes to escape from but cannot is considered to be his essence.” Mathis’ speaker begins by castigating herself for always wanting to keep things running smoothly, goes on to acclimate herself to corpses, admires the “propelling forward as if without thinking” in dog life, and pulls up short with a briny enlightenment. But the poems behave consistently, their diction and syntax not only representing but actually embodying the essence of the person, embraced after suffering.

Fortunately, Book of Dog doesn’t end here, mainly because the woman is not a dog. Her manner of speaking may seem highly controlled, but she is alternately “clenching and releasing” per her own psyche and character. As Adam Phillips also says, “That which the subject wishes to escape from but cannot is considered to be his essence.” Mathis’ speaker begins by castigating herself for always wanting to keep things running smoothly, goes on to acclimate herself to corpses, admires the “propelling forward as if without thinking” in dog life, and pulls up short with a briny enlightenment. But the poems behave consistently, their diction and syntax not only representing but actually embodying the essence of the person, embraced after suffering.

Book of Dog gains momentum and depth in its third section, even after the lessons are named. The final eighteen poems in “Essential Tremor” are splendid, deepening the book’s urgencies. Some of the poems comment on Mathis’ mission. In “The Wish,” she speaks of the sea: “All this back and forth / reflects the knowing I try to undo.” The ocean, the dunes, a dead seal appear in “Magnet”: “There is everything and nothing and why / shouldn’t you see yourself the same: incidental, / without privilege, hardly meant for even this.” Now, recalling the poems in the book’s opening, one sees that this has been theater, and that the identity “emerging” in the final poems is the voice that has been speaking from the beginning:

ALONE

The spider’s long legs

more than mother

the glistening three-tiered web.

Tearing it only brings her back

resolved again, and patient – but oh

this deliberate dismantling, this person

waving a hand through it, shoving

the broken threads to the side,

brushing strands away from my face,

cursing how something still sticks

and clings, so I can’t be done with it.

As if it were a plot, not a home

built with her very self. And this hunger –

this need to take all she can harvest

inside her, no end to her want –

No, how she keeps alive

is not luminous, but strict and necessary,

this moving sideways into the dark.

Early on, as wife and husband fail to communicate with each other, “she tried to disappear,” she wondered “how to make herself into someone / absent.” She kept house, “her usual vigilance.” she would “rush to wipe away, find the missing, / like this automatic retrieving of his sock.” In the end, even if her testament points to a changing perspective, she still finds a missing sock in every dead insect and mammal. Of a live bat’s dives around her house, she sees “nothing random / and that’s what I’m afraid of … Avoiding it, I am drawn to it.” She is still keeping house but now she has regained her speech. The poems recoup her essence in their form and sound. This is what they enact — by not changing anything essential about her.

Mathis has written a book of poems in a style strict and necessary, a delicate edifice of resonant imagery spun out of herself. She might try (or say she’s trying) to wipe away her knowledge, but it sticks, it can’t be undone. The great beauty here is what forms when a scarcity of means meets up with a luminous wish.

[Published by Sarabande Books on January 1, 2013. 70 pages, $14.95 paperback original]

Robert Pinsky’s essay “Poetry and Pleasure” may be found in Poetry and the World (1988).

Adam Phillips

Where can I find the Adam Phillips’ quotations? Thanks!

http://lleelowe.com

“In psychoanalysis there is

“In psychoanalysis there is always …” may be found in “Poetry and Psychoanalysis” in his book Promises, Promises. “That which the subject wishes to escape from …” may be found in “Narcissism, For and Against” (same book).

Again, thank you.

This is an

Again, thank you.

This is an excellent review, and I’ve already done a search for the Mathis poems I can find online, but I’ll probably be ordering the book too. I’m always grateful to you for these thoughtful pieces, which introduce me to poets I don’t know and am then keen to read. So my thank you embraces, by extension, all the work you do in this regard.

http://lleelowe.com