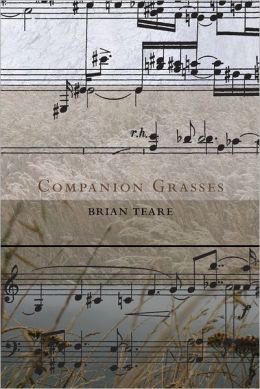

Brian Teare’s fourth book, Companion Grasses, is both a field trip and a search-and-rescue mission. It identifies parts of a natural world with a discriminating intensity inspired by writers like Gary Snyder and Rebecca Solnit. But it also seeks and gathers the words that not only specify one’s freed experience of that world, but also enact it. The going isn’t always easy. In fact, Companion Grasses is rife with doubts and even exasperation about language. As a lyric postmodernist, Teare circles back to that moment, contemplated by so many precursors all the way back to Emerson, when the individual yearns for and devises a language to communicate the experience of dissolution into a refreshed mode of seeing and saying. Rich with observation and citation, Companion Grasses is an homage as well as a path of discovery.

Brian Teare’s fourth book, Companion Grasses, is both a field trip and a search-and-rescue mission. It identifies parts of a natural world with a discriminating intensity inspired by writers like Gary Snyder and Rebecca Solnit. But it also seeks and gathers the words that not only specify one’s freed experience of that world, but also enact it. The going isn’t always easy. In fact, Companion Grasses is rife with doubts and even exasperation about language. As a lyric postmodernist, Teare circles back to that moment, contemplated by so many precursors all the way back to Emerson, when the individual yearns for and devises a language to communicate the experience of dissolution into a refreshed mode of seeing and saying. Rich with observation and citation, Companion Grasses is an homage as well as a path of discovery.

The book’s first section begins the hike along the coastline of northern California. In “White Graphite (Limantour Beach),” the first poem, Teare speaks directly to the smudging of identity. But also, he is orienting the reader to how the text wants to be read – as a kind of assured giving way, giving in:

matter a mere shift

in limits, even skin’s

a trick of the liminal :

touch here & I give

way to elsewhere :

“The book began in response to two concurrent experiences,” he said in a recent interview. “My first attempt to identify grasses and wildflowers with the aid of field guide, and a deep immersion in the central texts of 19th century Transcendentalism.” His mission evolved into portraying “the process that allowed for both immediacy of perception and the meditative space into which the hiker’s mind disappears.” The poetic form “responds equally to content, the historical and literary and autobiographical contexts in which a poem is written.”

In “Quakinggrass” he writes:

Beyond the frame –

context is a terrible weight —

to describe the water’s texture of

Gestures would never end –

an inch of surface

surfeit sense (“a detail overwhelms

Entirety,” writes Barthes) –

his storied thigh

scarred just so

There is a companion among these grasses, a man remembered affectionately whose attributes are parts of the observed beauty. There is also a tutelage in process – a gentle, encouraging but insistent nudging of the reader toward complicity in this new moment of regard. Context is a terrible weight because the poet would have us simply be there with him, context-less. But that would leave us alone within the pressure of desire, since context is our embedded fall-back position. Teare’s generosity partially consists in never quite depriving us of it (and he surely could), even while pointing to a more speculative mode. He writes, “What is meant by context : to pose / ruins the shot with intention – eye the I, he the camera …” So one strikes as context-less a pose as possible while preserving a “readerly” element. “Without a frame the image” is just “a lens of air” – and by saying so, that lens squints toward the visionary. The hikers “kept trying to stop meaning / from taking final shape — / a series, a story” — but the story is always lurking.

There is a companion among these grasses, a man remembered affectionately whose attributes are parts of the observed beauty. There is also a tutelage in process – a gentle, encouraging but insistent nudging of the reader toward complicity in this new moment of regard. Context is a terrible weight because the poet would have us simply be there with him, context-less. But that would leave us alone within the pressure of desire, since context is our embedded fall-back position. Teare’s generosity partially consists in never quite depriving us of it (and he surely could), even while pointing to a more speculative mode. He writes, “What is meant by context : to pose / ruins the shot with intention – eye the I, he the camera …” So one strikes as context-less a pose as possible while preserving a “readerly” element. “Without a frame the image” is just “a lens of air” – and by saying so, that lens squints toward the visionary. The hikers “kept trying to stop meaning / from taking final shape — / a series, a story” — but the story is always lurking.

Teare’s formal choices embody the tensions and conflicts of the mind at work. The poems leap ahead and pause, dilating with an essayistic thrust, then favoring compression. The variety and surfeit of the actual test the capacity to witness everything, as in this block of prose from “Tall Flatsedge Notebook”:

there was this sense of good work done, whole

earth’s curve panorama : a gray whale, migratory

Pacific. Sense of almost spring, flowering grasses

dead, almost done leaving, it was there, nearer me

than you : winter-weathered stemmy thing ending

black asterisks : seeds, sheaths, not much to see,

I wanted a name for it – why?

Although founded on affirmation, Companion Grasses interrogates itself habitually. Having found a site of peace and touched the thin membrane between any two things, it still asks: what shall we do, how and what shall we be? The exhilaration of perceiving the world in shape-shifting terms triggers thorny issues of responsibility. Below, the opening lines from “The Very Air (Faith Reason)” (which recalls “a lens of air” above):

but we tire of spirit sight

striving always for elsewhere as we are

so much among phenomena God

loses luster where we are local only inured

to detail starting small with grasses

A side-trip: Companion Grasses provides an occasion to ask, “what is the status of lyricism in postmodern poetry?” When Paul Hoover mentions lyricism in his introduction to the just-published second edition of Postmodern American Poetry (Norton), it is only to delimit and deflate the term’s usage. His anthology’s genealogy begins with Charles Olson who recommended “getting rid of the lyrical interference of the individual ego,” and moves toward Language poets and others who (per Hoover) “see lyricism in poetry not as a means of expressing emotion but rather in its original context as the musical use of words.” While conceding that the works of Olson, Creeley, Levertov and Duncan weren’t “necessarily impersonal,” Hoover’s overall preference is for only those poets who oppose “the central values of unity, significance, linearity, expressiveness, and any heroic portrayal of the bourgeois self and its concerns.”

A side-trip: Companion Grasses provides an occasion to ask, “what is the status of lyricism in postmodern poetry?” When Paul Hoover mentions lyricism in his introduction to the just-published second edition of Postmodern American Poetry (Norton), it is only to delimit and deflate the term’s usage. His anthology’s genealogy begins with Charles Olson who recommended “getting rid of the lyrical interference of the individual ego,” and moves toward Language poets and others who (per Hoover) “see lyricism in poetry not as a means of expressing emotion but rather in its original context as the musical use of words.” While conceding that the works of Olson, Creeley, Levertov and Duncan weren’t “necessarily impersonal,” Hoover’s overall preference is for only those poets who oppose “the central values of unity, significance, linearity, expressiveness, and any heroic portrayal of the bourgeois self and its concerns.”

Reginald Shepherd devised the term “lyric postmodernism” to underscore the vibrant continuity of lyric experimentation to the present moment, and to emphasize the obvious fact that lyricism is capable of doing much more than expressing those horrid bourgeois emotions. Teare’s collection claims Robert Duncan as a forebear, takes inspiration from Robin Blaser and Ronald Johnson, and also finds companionable influences in Brenda Hillman, Susan Howe, Carl Phillips, Gillian Conoley, and Hoover himself. His citations honor his artistic roots and schooling: Whitman, Emerson, Thoreau, Heidegger, Barthes, Merleau-Ponty. Teare writes, “thick, the poem transcriptive / rather than descriptive. // As Duncan says, ‘In faith / my sight is sound.’” There is recognition of the power of transcendence – but the self’s traces remain stubbornly to prove there is a point of departure. He quotes Luce Irigaray: we “have to renounce projecting / in the solitary manner the horizon // of a world as transcendence.” Yet Teare is the solitary man who says so in a world comprising companions. In “What’s” he writes, “identity / becomes / its minimal matter / fragile” — a distillation, but not necessarily an erasure.

I don’t mean to discount the value of the effort to cleanse oneself of the “manner.” On the contrary, in Teare’s work it yields deeply profound movements of the spirit and mind into which the reader may blend and blur. A stunning elegy, “To begin with desire,”

I don’t mean to discount the value of the effort to cleanse oneself of the “manner.” On the contrary, in Teare’s work it yields deeply profound movements of the spirit and mind into which the reader may blend and blur. A stunning elegy, “To begin with desire,”

(which quotes Duncan) is enshadowed by the 2007 death of his father, Robert J. Teare, who appears much like the landscape: “how near I was to him / in my ambivalence; he was // the thing I held away / & so held it closer.” The first-person persists with a purpose. There is no landscape of mourning without it, no context. In “Star Thistle,” Teare grieves for Reginald Shepherd (“after fourteen years of living with HIV … after chemotherapy’s nausea & neuropathy”) by acknowledging the toxic presence of a plant that “ensures its slow destruction of an ecosystem … uncanny it survives drought & thrives / off wildfire both.” More:

Whitman says,

Now I am terrified

at the Earth, it is that calm and patient

as it undoes itself, undoing that toughens

to give way relentlessly to nothing

but its own propagation : the Earth

undoes itself as each life undoes itself & to what end

is what terrifies me as after the hike

I try with salve to soothe the blisters that deepen & weep weird clear fluid :

the day before Reginald died, we spoke on the phone

but morphine filled his speech

so completely

it was terrible to listen to him, disappearing

even as he said I love you & I echoed him, the last thing

I could hear

before I had to say goodbye

filled with the certainty I’d failed to witness the death of a friend I’d loved …”

This is where Companion Grasses ends, with a fear that one has failed to witness things adequately. It occurs to me that this agitation and dread dwell in these poems from the outset – but what begins with disquiet about language concludes with a different distress. Teare has written a book of sweeping movements and tidal cerebral and emotional rhythms. Like the sonatas of Charles Ives, another of his touchstones, his “hike’s trajectory … repeats central themes gesturally, // through variation : to begin / with the desire for accuracy.”

[Published by Omnidawn Publishing on April 1, 2013. 136 pages, $17.95 paperback original]

On A Walk

Thank you once again for a stimulating review of Mr Teare’s fascinating collection. A few errant thoughts. Of going out into the world, into Nature, to look for sense – if not for order – Emerson wrote: “We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree; but the whole, of which these are shining parts, is the soul.” To the degree that I think about it much, or about how it informs what/how I write – if I follow the conversation – language can transcend no thing it is directed at. This tension is called communication. These limitations are designed only to intimate; I don’t believe for a minute that it is the world that requires transcendence. As for the “manner” cleansing project and the opposition to “the central values of unity, significance, linearity, expressiveness, and any heroic portrayal of the bourgeois self and its concerns” (“the bourgeois self”, that’s rich!), I don’t think these are quite the same thing. At some point all poems of merit must convince with reason, and if the disturbed poem is a sharp and uneasy contemplation about the limitations, and if the mad poem fails its own reasonable test, sometimes it’s the reader who fails this test. Sometimes the soul is misplaced. Sometimes it rains. Only my opinion.

Still arguing for reason?

There is “reason” dwelling within Brian Teare’s poetry but it isn’t the kind that disparages unreasonable desires such as the wish to remain in a state of complete agreement — I don’t mean dialectical agreement — with one’s surroundings and loved ones. See the final part of Slate’s essay where he talks about the fear and the sense of restriction. The desire is manifest in the poems but also the acknowledgment of our rational boundaries. Transcendence isn’t “required” in this vision of life (in the poems). But it is glimpsed and this sets off Teare’s language.

arguing for reason

the wild

arguing for reason

the wild grasslands

rational boundaries

in the distance

I agree with you