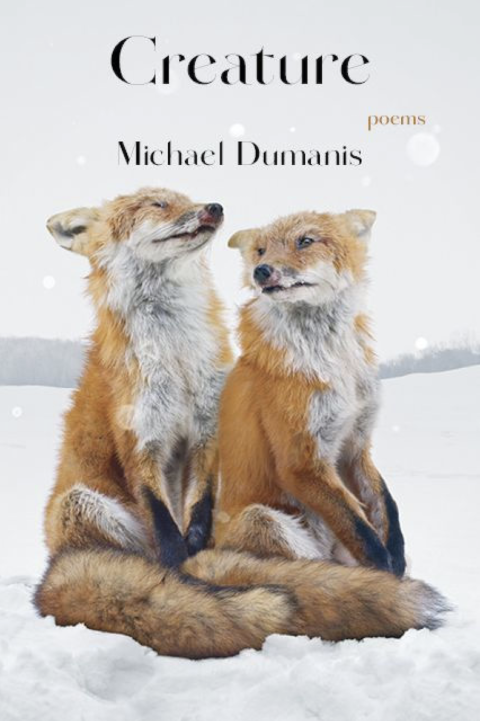

The poems in Michael Dumanis’ new collection, Creature, concatenate in stunning succession with sprezzatura, testifying to what Wallace Stevens claimed in his poem, “Final Soliloquy Of The Final Paramour,” that “God and the imagination are one./ How high that highest candle lights the dark.” What Stevens asserts about the divinity of the imagination implies as much mystery as it does earthly certainty. Throughout Creature, Dumanis witnesses to the evanescent divide between the divinely ineffable and the creaturely obvious. “I’m fully posable, a leather and clay creature / with the capacity to waltz and do the Twist” he claims in the first two lines of the first poem titled “Natural History,” establishing the thematic middle c for the rest of the poems in the book that testify to the “fully posable” positions that both his body and his mind are capable of assuming.

The poems in Michael Dumanis’ new collection, Creature, concatenate in stunning succession with sprezzatura, testifying to what Wallace Stevens claimed in his poem, “Final Soliloquy Of The Final Paramour,” that “God and the imagination are one./ How high that highest candle lights the dark.” What Stevens asserts about the divinity of the imagination implies as much mystery as it does earthly certainty. Throughout Creature, Dumanis witnesses to the evanescent divide between the divinely ineffable and the creaturely obvious. “I’m fully posable, a leather and clay creature / with the capacity to waltz and do the Twist” he claims in the first two lines of the first poem titled “Natural History,” establishing the thematic middle c for the rest of the poems in the book that testify to the “fully posable” positions that both his body and his mind are capable of assuming.

In a stream of “strange relations,” Dumanis poems evince innate wonder and startling originality. One can turn to any poem and find lines such these from his poem “The Kidnapped Children” that captivate and surprise:

First we were taken by surprise, away, for granted,

but later taken care of, taken in.

A bath was run. We were prohibited from drowning.

The speaker in Creature, an ageless adult “child,” remains in his tub, writing on water while his Ashbery-like minders provide him with a magical pen for writing both profoundly and playfully. The entertaining antiphonal voices of his adult wisdom and child-like innocence play off each other throughout. It’s as though his innocent wondering has matured preternaturally into wild sophistication that has only grown, seemingly exponentially, into full-blown risible sagacity. While one keeps waiting for him to jump off the deep end of sense, Dumanis somehow manages to keep his balance at the world’s edge where anyone could evanesce “into the air.” In a kind of credo about the mortal fragility that colors his poems, he writes in his poem “The World”: “… time pauses long enough for us to tune / the tiny radios inside our chests / to turn them up so we can hear each other / as people blow toward us like flurries of light/to tell us the names of people they love.”

By welding conventional sense with diachronic conceits, Dumanis frees himself up to make surprisingly new “human” sense that’s also creaturely in language flowing with “no irritable reaching.” “It’s so amazing what we get to see,” he writes at the conclusion of his poem “Natural History.” And yet he isn’t hesitant to “destroy“ his poems like a poetic Shiva in order to write new poems, confessing in the last poem of the book, “The Idea of Order,” in a nod to his mentor Wallace Stevens, “I am the destroyer of words, submerged to my crown in the cyan sea, / dropping the spume with my many arms.”

By welding conventional sense with diachronic conceits, Dumanis frees himself up to make surprisingly new “human” sense that’s also creaturely in language flowing with “no irritable reaching.” “It’s so amazing what we get to see,” he writes at the conclusion of his poem “Natural History.” And yet he isn’t hesitant to “destroy“ his poems like a poetic Shiva in order to write new poems, confessing in the last poem of the book, “The Idea of Order,” in a nod to his mentor Wallace Stevens, “I am the destroyer of words, submerged to my crown in the cyan sea, / dropping the spume with my many arms.”

In referencing this classical trope of aligning creation with destruction, Dumanis revels in the generative paradox of poetry. In his ends are his beginnings. I am hard-pressed to think of another contemporary poet who incorporates both contemporary and ancient sensibility so memorably in poetry that resonates as post postmodern and mythological, both comedic and highly serious. The poems in Creature refresh and remind, allude and update, steal and make new, inviting the reader to address both his creaturely-ness and his human difference, both his atavism and his terrifying modernity. This dual strategy juxtaposes eschatological foreboding with routine but inherently strange life, often with what seems like impossible humor, as in these lines also from “The Idea of Order”: “I am a cloud or a silver machine. / Because I was raised by people, I became / bonded to people. I skipped over the crab grass with the other girls … Much like a person, I have to steel myself / to like another person other than myself.” Who else is writing today with such an engaging, poignant admixture of both prelapsarian elan and postmodern elegance?

[Published by Four Way Books on September 15, 2023, 89 pages, $17.95 paperback]