Books about the psychopathology of the children of trauma survivors form a growing sub-genre of Jewish Holocaust literature. In 2012, an Israeli study went further, claiming to find signs of trauma among the grandchildren. Haaretz reported that “out of 30 women in this second-generation group who testified that their parents were cold and distant, 20 of them have teenage children who complain of similar experiences with their parents. The same dynamic was reported by 14 children of 30 second-generation fathers.” (Some 500,000 Holocaust survivors emigrated to Israel after the war.) This PTSD is broadly regarded as worthy of treatment and counseling. But researchers dispute the data, and the ensuing generations have been charged by some critics with expropriating and fetishizing the trauma to cultivate victimhood.

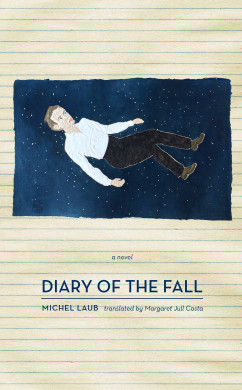

Michel Laub’s novel Diary of the Fall illuminates the tragic nuances of multi-generational angst and failure as told by a grandchild of an Auschwitz survivor. Through spare prose cast in brief, halting segments, Laub tells a familial and personal story that creates psychological density — not only through plot and drama, but also the sound and shape of language struggling to rise to the level of the unresolved. Laub achieves more in fiction than most memoirs manage through that genre’s overbearing knowingness.

Michel Laub’s novel Diary of the Fall illuminates the tragic nuances of multi-generational angst and failure as told by a grandchild of an Auschwitz survivor. Through spare prose cast in brief, halting segments, Laub tells a familial and personal story that creates psychological density — not only through plot and drama, but also the sound and shape of language struggling to rise to the level of the unresolved. Laub achieves more in fiction than most memoirs manage through that genre’s overbearing knowingness.

The narrator’s grandfather, an Auschwitz survivor whose family perished there, arrived in Brazil’s Porto Alegre after the war. (Porto Alegre, the capitol of the far south state of Rio Grande do Sol, was also a favored haven for emigrating Germans, Nazis or otherwise, though this is not mentioned.) The grandfather took up the odd, obsessive, and solitary habit of compiling a sort of encyclopedia of the ordinary — bland definitions of perfect things — and never discussed Auschwitz. His son, successful in small business, remained aloof from his own son and also began to write in private when his health began to fail. Now, the third generation writes in order to confront these intertwined pasts.

But the narrator’s story begins with a cruel prank played on a Christian boy named João who attended his Jewish school in 1980’s Porto Alegro. This mistreatment resulted in a serious injury. But it also stung the narrator who both participated in the prank and later fingered his accomplices. Thus, the narrative starts not with the griefs of post-genocide but with an unachieved expiation, the staining sins of the perpetrator. “Everything I had lost since I was fourteen” becomes both the subject of the story and the spur to comprehend a sprawling loss.

The heaviness of the loss presents Laub’s greatest challenge. The novel’s tone suggests a forced march through memory, oppressed by alcohol and failed marriages. Brevity, a recurring pattern of memory, and the paced revelation of present circumstances work together to keep the narrative from sinking under its own weight. Chapters consist of short numbered chunks as if the speaker is struggling for form, order, and concision.

The heaviness of the loss presents Laub’s greatest challenge. The novel’s tone suggests a forced march through memory, oppressed by alcohol and failed marriages. Brevity, a recurring pattern of memory, and the paced revelation of present circumstances work together to keep the narrative from sinking under its own weight. Chapters consist of short numbered chunks as if the speaker is struggling for form, order, and concision.

A constant theme of Holocaust memorials is the command: never forget. Laub honors that directive by acknowledging the erosion (and banality) of memory and questioning the value of testimony.

20.

Would it make any difference if the things I’m describing are still true more than half a century after Auschwitz, when no one can bear to hear about it anymore, when even to me it seems old-fashioned to write about it, or are those things only of importance to me because of all the implications they had for the lives of all those around me?

Furthermore, the narrator echoes those criticisms of third-generation members who “reproduce those feelings without really suffering.” His own incessant rehashing of events comes under scrutiny:

Telling the story of your life from when you were fourteen involves, I repeat, accepting the facts — even gratuitous facts or facts that, due to circumstance, defy all logic — can nevertheless be linked together as cause and effect. As if by talking about Joao and about the last time we spoke, shortly before the end of eighth grade, I were looking for the origin of what happened on that trip to Porto Alegre, almost three decades later …

… a trip during which he returns to visit his parents with new information about his father’s health. In the above passage, the words “As if” are key: cause and effect in relationships, while scented with facts and necessary for personal mythology, exist only in the imagination.

Primo Levi, whose name and work are invoked in Diary of the Fall, wrote in his essay “The Memory of Offence” how wishful thinking distorted the consciousness of camp prisoners. People “fabricate for themselves a convenient reality … and reciprocally administered [it] to others.” With remarkable subtlety, Laub allows the withdrawn behavior of the narrator’s grandfather, so shameful to his son and offensive to his grandson, broadly to suggest more widespread, common yet still complex depressiveness.

Born in Porto Alegre in 1973 and named one of Granta’s ‘best young novelists’ in 2012, Laub worked as a journalist for a decade before turning to fiction. For those fiction and memoir readers who crave the recalled moment of revelation, too bad! Laub is more invested in expressing the density of actuality. Ultimately, we arrive at a knotty set of present circumstances and speculations that have triggered the speaking in the first place. A life is filled in piece by piece, shadow by shadow.

Born in Porto Alegre in 1973 and named one of Granta’s ‘best young novelists’ in 2012, Laub worked as a journalist for a decade before turning to fiction. For those fiction and memoir readers who crave the recalled moment of revelation, too bad! Laub is more invested in expressing the density of actuality. Ultimately, we arrive at a knotty set of present circumstances and speculations that have triggered the speaking in the first place. A life is filled in piece by piece, shadow by shadow.

And yet, in the end there is enough light to satisfy those who may otherwise recoil at this unsparing novel. However, even the narrator’s late arrival at a more satisfying relationship with others (which is, of course, the “event” that prompts the telling), Laub’s speaker remains true to his nature: “I wouldn’t want to tell another of those stories about how being in an extreme situation forces us to reevaluate our whole life, as if the prospect of someone close to us dying made us realize how unimportant everything else is … but looking back that’s pretty much how things happened.”

[Published by Other Press on August 26, 2014. 240 pages. $16.95 original paperback.]