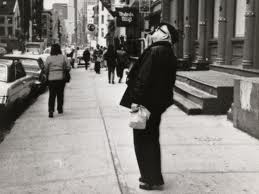

In 1981 at the age of 70, Max Frisch bought a loft at 123 Prince Street, New York. His eighth and final novel, Bluebeard, was finished and ready for the printer. A few years later, he would write a final play (he had produced eleven). For the moment, he set to work on his third Tagenbuch, a collection of short pieces mixing memoir, lyric description, political commentary, thoughts-in-passing, and dialogue. Sketchbook 1946-1949 had colored in his aesthetic and political credo. Sketchbook 1966-1971 spilled over with outrage over the Vietnam war, darkened further by the failure of his marriages. Those Sketchbooks also featured his prickly and provocative “Questionnaires”:

15. When did you stop believing you would become wiser – or do you still believe it? State your age.

16. Are you convinced by your own self-criticism?

17. What in your opinion do others dislike about you, and what do you dislike about yourself? If not the same thing, which do you find it easier to excuse?

18. Do you find the thought that you might never have been born (if it ever occurs to you) disturbing?

In an afterword to Drafts for a Third Sketchbook, editor Peter Von Matt emphasizes that these multi-genre diaries comprise “a literary form as much as the novel, the short story, the drama … [not] cursory, preliminary jottings. They have all been through a process of reduction and intensification and take their place in the thematic web of a planned composition.” Frisch destroyed almost all of the incidental note-taking he did not want us to read, and burned the first two novels he wrote in his 20’s. The Sketchbooks accumulate resonance as the pages turn. The entries are both meticulous and speculative, packed tight and open-ended.

In an afterword to Drafts for a Third Sketchbook, editor Peter Von Matt emphasizes that these multi-genre diaries comprise “a literary form as much as the novel, the short story, the drama … [not] cursory, preliminary jottings. They have all been through a process of reduction and intensification and take their place in the thematic web of a planned composition.” Frisch destroyed almost all of the incidental note-taking he did not want us to read, and burned the first two novels he wrote in his 20’s. The Sketchbooks accumulate resonance as the pages turn. The entries are both meticulous and speculative, packed tight and open-ended.

Most of Drafts for a Third Sketchbook was completed by the end of 1982. Its preoccupations include aging and death, Reagan’s America and U.S. dominance of Europe and elsewhere, life in New York, travel, women (then and recalled), his alcoholism, Israel, and the waning of creative power. Frisch follows the last days of his close friend Peter Noll, a Swiss professor of criminal law and a current affairs writer, who died in September, 1982. He comments on his relationship with the unnamed young woman who lives with him, a dry acceptance of separate existences.

Although Frisch had no desire to limn portraits or develop scenes, there is nothing inadvertent about the Sketchbook’s fragmentary encounters and moments. Reviewing Frisch’s novel The Man in the Holocene, D.J. Enright found in it “a cloud that grows darker and more diffuse as we proceed.” The cloud extends over the personal glimpses in the Sketchbooks. In 1947, Frisch met Bertold Brecht in Zurich; it was Brecht who taught that the theater must escape from culture, “must be allowed to remain a superfluous thing,” since when we are most free we live for the superfluous (which is everything not falsified by power). The Sketchbooks both contain and embody essential superfluities.

Although Frisch had no desire to limn portraits or develop scenes, there is nothing inadvertent about the Sketchbook’s fragmentary encounters and moments. Reviewing Frisch’s novel The Man in the Holocene, D.J. Enright found in it “a cloud that grows darker and more diffuse as we proceed.” The cloud extends over the personal glimpses in the Sketchbooks. In 1947, Frisch met Bertold Brecht in Zurich; it was Brecht who taught that the theater must escape from culture, “must be allowed to remain a superfluous thing,” since when we are most free we live for the superfluous (which is everything not falsified by power). The Sketchbooks both contain and embody essential superfluities.

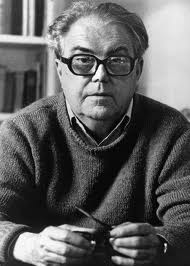

Frisch (1911-1991) is generally regarded as the greatest Swiss contributor to German literature of the 20th century. The enigma of identity was his constant subject. In his novel I’m Not Stiller (1954) he wrote, “You can put anything into words, except your own life.” The characters in his prose fiction and plays long for authentic existence but are hobbled by the mendacious systems erected around them. His speakers pursued their biographies anyway, narrating with a hyper-aware density (which is not the same thing as an excess of words). In the final Sketchbook, Frisch criticizes, often harshly, but also looks critically at himself. He writes:

I’m turning into an old man.

You become an old man when you don’t feel committed to anything any more, when you don’t think you owe anyone in the world anything, and for that you don’t have to need a walking stick or be in a wheelchair … What frightens me at the moment is my increasing thoughtlessness towards friends, my increasing indifference to public events, my increasing freedom … What has Israel to do with me?

The 1982 Israeli incursion into Lebanon is on his mind, especially the massacres at the Sabra and Shatila camps. Reagan (who was the same age as Frisch) was expanding his nuclear arsenal and the French were making the neutron bomb. Frisch’s panic over this escalation will resonate with those who remain concerned about the proliferation of these weapons in Iran and North Korea. The extended, barbed anecdotes of the second Sketchbook are gone now (such as his piqued but also risible rendition of having lunch with Kissinger at the White House), but Frisch never lacked for material. He loved New York even when while saying, “Basically America (the USA) is not a warmongering but simply a commercial society war as the continuation of business by other means.” He also drew a bead on American culture at large and its pushiness abroad:

The 1982 Israeli incursion into Lebanon is on his mind, especially the massacres at the Sabra and Shatila camps. Reagan (who was the same age as Frisch) was expanding his nuclear arsenal and the French were making the neutron bomb. Frisch’s panic over this escalation will resonate with those who remain concerned about the proliferation of these weapons in Iran and North Korea. The extended, barbed anecdotes of the second Sketchbook are gone now (such as his piqued but also risible rendition of having lunch with Kissinger at the White House), but Frisch never lacked for material. He loved New York even when while saying, “Basically America (the USA) is not a warmongering but simply a commercial society war as the continuation of business by other means.” He also drew a bead on American culture at large and its pushiness abroad:

… an immense boredness in our society. What has brought it about? A society that produces death as never before, but death without the transcendental, and without the transcendental there is only the present; to be more precise: our life as a fleeting moment of emptiness before death.

✜

Helmut Kohl, the new German chancellor, was in Washington (the middle of November) and a senior official of the White House assured the reporters: “I know of no issue on which the two gentlemen disagreed.”

An ideal European, then.

Nonconformity is a tough assignment for the Swiss, and Frisch enjoyed practicing it outside of Zurich (where he was born and died). His country’s tidy pieties enraged him, as when quoting Noll: “It has become Christian to obey the authorities under almost all circumstances.” His editor Peter Demetz said Frisch “has been always happiest where he was not.” In the final Sketchbook, that other place appears in a series of pieces that describe an imaginary place, “one of those oldish houses, a wooden house, if you like, (painted white) like the houses in New England, a former villa with thirteen rooms and a veranda.” The house and its surroundings are filled in, and then the man must care for it, painting shutters. The dream floats here between pages noting the reality of advanced age and death:

Nonconformity is a tough assignment for the Swiss, and Frisch enjoyed practicing it outside of Zurich (where he was born and died). His country’s tidy pieties enraged him, as when quoting Noll: “It has become Christian to obey the authorities under almost all circumstances.” His editor Peter Demetz said Frisch “has been always happiest where he was not.” In the final Sketchbook, that other place appears in a series of pieces that describe an imaginary place, “one of those oldish houses, a wooden house, if you like, (painted white) like the houses in New England, a former villa with thirteen rooms and a veranda.” The house and its surroundings are filled in, and then the man must care for it, painting shutters. The dream floats here between pages noting the reality of advanced age and death:

If I wake up during the night not knowing where to find the courage for the next day and then go back to sleep – it gets up when I’m making coffee at the latest, like a faithful dog that’s slept beside my bed: the courage! – to pick up the telephone, and later on go into town and talk to friendly people, and to forget what you knew during the night, and not to see the future, as if you were being led by a guide dog. Today I was almost run over by a truck on West Broadway.

When the Paris Review interviewed him in 1989, Frisch said, “I don’t want to write about experiences I’ve had that I’ve already written about. I could write them better, but that’s not so interesting. I’m experiencing something now and I don’t know what it is. And that makes me silent.”

There is much poignant silence in Drafts for a Third Sketchbook, much consideration of the “something” he is considering in the moment. “He would rather risk an astonishing failure than to repeat himself,” observed Demetz. In this last notebook, Frisch wagers not against death but its foreign-ness, as ever, starting from scratch with a sense of being “all at sea … at a loss”:

There is much poignant silence in Drafts for a Third Sketchbook, much consideration of the “something” he is considering in the moment. “He would rather risk an astonishing failure than to repeat himself,” observed Demetz. In this last notebook, Frisch wagers not against death but its foreign-ness, as ever, starting from scratch with a sense of being “all at sea … at a loss”:

In general I envy anyone who has been through a school of thought, no matter which; whether as a Jesuit or a Protestant or a Marxist or a Cabbalist; even if such a person later changes their position, they remain within a system of coordinates. Whenever I get involved in abstract reasoning, I’m all at sea and feel I’m as windbag and it doesn’t make things easier if the other person’s a windbag as well, and that does happen. I have to depend on experiences that leave me conceptually at a loss and therefore remain on a narrative level. It’s my nature that anything that cannot be presented in concrete terms remains foreign to me.

[Published by Seagull Books on December 15, 2013. 194 pages, $21.00 hardcover.]