A young American poet working towards an M.F.A. today most likely will not encounter a poem by Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) nor find his name or work discussed in pedagogical texts. From among the German romantic poets of the 19th century, maybe one reads a little Novalis or Hölderlin, or some lyric prose by Von Kleist. Yet Heine, firing salvos at German nationalism and satirizing his culture’s pretentions, appears more like some of our own pugnacious poets even if his rhyming trochaic tetrameters sound anachronistic. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, they banned and destroyed his books, even though both Schumann and Schubert had composed music for his lyrics – but Heine had foreseen this and the Holocaust to follow, having famously written in 1823, “Wherever books will be burned, people also, in the end, are burned.”

In his compact biography, Heinrich Heine: Writing the Revolution, George Prochnik conjures a restless and aggrieved malcontent who met and often tempted resistance and resentment at every turn – from his secular Jewish family, fellow students (there were several challenges to duels), the universities that would not employ him, the censors, and the women who never quite appreciated his noble qualities. There would be no consensus between the conflicting forces within him; a focus on the turbulent clashing of urges and visions is the secret sauce of Prochnik’s portrayal which lavishes most of its attention on Heine’s youth and early adulthood in Germany. By 1831 Heine had decamped to Paris, a voluntary move that “became a forced exile after an arrest warrant was issued in his name for affronts to royalty and ‘instigations to discontent.’ This writ was renewed annually, accompanied by posters [that] added tips on identifying him: he had ‘a pointed nose and chin; and markedly Jewish manner. He is a libertine, whose wasted body denotes dissipation.’”

In his compact biography, Heinrich Heine: Writing the Revolution, George Prochnik conjures a restless and aggrieved malcontent who met and often tempted resistance and resentment at every turn – from his secular Jewish family, fellow students (there were several challenges to duels), the universities that would not employ him, the censors, and the women who never quite appreciated his noble qualities. There would be no consensus between the conflicting forces within him; a focus on the turbulent clashing of urges and visions is the secret sauce of Prochnik’s portrayal which lavishes most of its attention on Heine’s youth and early adulthood in Germany. By 1831 Heine had decamped to Paris, a voluntary move that “became a forced exile after an arrest warrant was issued in his name for affronts to royalty and ‘instigations to discontent.’ This writ was renewed annually, accompanied by posters [that] added tips on identifying him: he had ‘a pointed nose and chin; and markedly Jewish manner. He is a libertine, whose wasted body denotes dissipation.’”

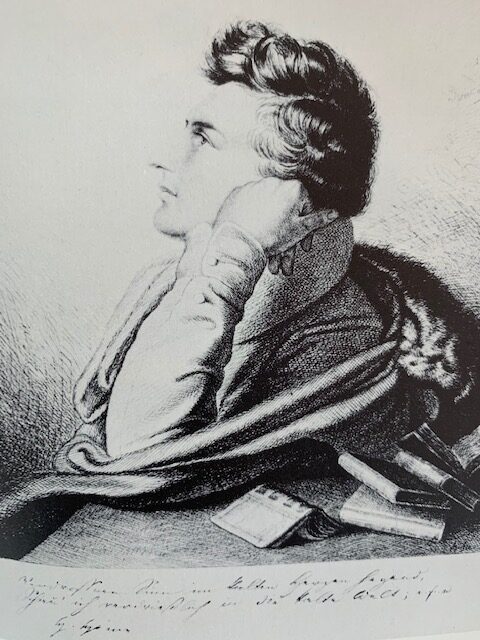

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine was born in Düsseldorf, then a town of 16,000 people governed by the occupying French and the liberating Napoleonic Code. But by 1814 and the Congress of Vienna, the German states regained control. Heine’s lifelong exalted visions of spiritual and bodily emancipation were inspired by his hero Napoleon – and his unabating disparagement of reactionary intolerance was provoked by just about everything and everyone else. His first poems were published in a newspaper in 1817. He may not have been going anywhere, but he was already depicting himself as a dissenter: “Leaning against the mast I stood / And counted each wave that passed; / Farewell, dear native land of mine, / My ship is sailing fast!” (“Taking Ship”). Meanwhile, he shipped off to law school in Bonn per his family’s wishes, particularly those of his uncle Salomon, a successful banker who seemed willing to help the wayward young man find a profession. In Bonn, Heine met and was encouraged by August Wilhelm Schlegel (he would later mock Schlegel). In 1821, his first collection of poems, Gedichte (Poems), appeared and he moved to Berlin.

The facts of the life are intriguing – but what makes Prochnik’s narrative so vigorously engaging is the sense that he gets Heine and perhaps identifies with the aspirations and griefs of the outsider. This connection emerges through tone – and by not getting too deep into the weeds of literary analysis. For instance, in 1825 Heine went through the motions of converting to Lutheranism. (In 1822, edicts were issued prohibiting Jews from attaining academic posts, and Heine wanted to be the literary man on campus.) Here is how Prochnik describes the episode:

The facts of the life are intriguing – but what makes Prochnik’s narrative so vigorously engaging is the sense that he gets Heine and perhaps identifies with the aspirations and griefs of the outsider. This connection emerges through tone – and by not getting too deep into the weeds of literary analysis. For instance, in 1825 Heine went through the motions of converting to Lutheranism. (In 1822, edicts were issued prohibiting Jews from attaining academic posts, and Heine wanted to be the literary man on campus.) Here is how Prochnik describes the episode:

“… new regulations meant the only way he would be able actually to practice law would be as a Christian. This requirement had its own implications for Hein’s self-respect, though fully half of Berlin’s Jewish community were said to have converted in the period … He was the only member of his family who harbored the smallest objection to the step, he told his friends. For Uncle Salomon and his mother, the whole question of belonging was economic. If your livelihood depended on reeling off the holy singsong about blessed Jesus – well, then, that was the form in which redemption, here on earth, was bound to come. Just get your Gentile ticket and be done with it. He never did practice law. As for the thriving fortunes of Heine’s sister and two brothers, Prochnik remarks, “Two barons and a princess within a generation. Not bad for one middling Jewish family in early nineteenth-century Germany.”

Heine deeply resented inherited privilege and wealth – and any constraints imposed by one’s identity. So on the one hand, he converted because his given identity should not be an impediment – and he disparaged the “spiritual invalidism” of old-time religions. On the other hand, he bristled at having to mollify the anxieties of those in power. Prochnik’s Heine inhabits the turbulent space between the auspicious potential of humanity (he appreciated Hegel’s assertion that history has a purpose) and the depressive perception of broken promises. Similarly, he was caught somewhere between his empirical self and his ideal one – not that this bind was ever apparent or made a topic of his work. Prochnik avers Heine had “tried to make his outward being as different as possible from his inner one lest the latter destroy him.” “To Edom,” written in 1824, emits the “scoffing and scourging” tone of his grievances – at the time, his candor about anti-Semitism was regarded as a lyrical phenomenon:

To Edom

A brotherly forbearance

Has united us for ages:

You, you tolerate my breathing

And I tolerate your rages.

Just a few benighted eras

Found you feeling rather odd,

Coloring your loving-pious

Little talons with my blood.

Later we became more cordial,

Day by day our friendship grew –

For I also started raging

And I almost seem like you.

Prochnik does an adequate job of tersely describing the evolving sounds of Heine’s work – though why his work was heard as innovative is never quite clear. He describes the innovation as “an effort to take readers behind the scenes in the voicing of desperation and desire. The tearing down of customary forms of self-expression provides a kind of object lesson in cultivating a revolutionary example.” But was Heine’s attitude the whole show? He identified most closely with Byron — but Heine evinces none of Byron’s panache or expansiveness. Prochnik points out “the famous Heine Stimmungsbrechung – breaks in tone that happen often at the ends of poems” – and he mentions Heine’s incorporation of German folk poetry’s “customary rhythms, in the form of four-line stanzas with several primary stresses and shifting counts of unstressed syllables … so well-known that the pattern came to be called Heinestrophe.” You may find it useful to have a volume of the poems to refer to – as well as a Heine timeline, including the dates of his major publications.

But Prochnik finely captures the major moments, such as the young Heine’s trip to visit Goethe – and perhaps gain his endorsement. With the 1827 publication of his Book of Songs, Heine’s reputation took off; this volume was a new and selected collection that ultimately went through 13 reprints during his life. It also gave him the confidence to kick sand in Goethe’s face. Prochnik writes, “Since visiting Goethe, he had deepened his commitment to the principle that the age of lyric verse was finished – superseded by new material realities and coinciding struggles for progress. ‘The hubbub of a common European brotherhood of peoples,’ with its ‘sharply mingled pain and jubilation,’ made its own kind of music … Indeed, the age of art, which Goethe had emblematized, was now in retreat. Heine proclaimed in 1828, ‘A new era, a new principle’ was emerging that required aesthetics to be fully engaged with ‘the movement of the time.’” Sound familiar? But Prochnik won’t let Heine off so easily, noting that Goethe had said about him, “‘Though he spoke with the tongue of men and angels, his voice was as sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal’ … Goethe had hit on a terrible secret: Heine didn’t know how to love.”

But Prochnik finely captures the major moments, such as the young Heine’s trip to visit Goethe – and perhaps gain his endorsement. With the 1827 publication of his Book of Songs, Heine’s reputation took off; this volume was a new and selected collection that ultimately went through 13 reprints during his life. It also gave him the confidence to kick sand in Goethe’s face. Prochnik writes, “Since visiting Goethe, he had deepened his commitment to the principle that the age of lyric verse was finished – superseded by new material realities and coinciding struggles for progress. ‘The hubbub of a common European brotherhood of peoples,’ with its ‘sharply mingled pain and jubilation,’ made its own kind of music … Indeed, the age of art, which Goethe had emblematized, was now in retreat. Heine proclaimed in 1828, ‘A new era, a new principle’ was emerging that required aesthetics to be fully engaged with ‘the movement of the time.’” Sound familiar? But Prochnik won’t let Heine off so easily, noting that Goethe had said about him, “‘Though he spoke with the tongue of men and angels, his voice was as sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal’ … Goethe had hit on a terrible secret: Heine didn’t know how to love.”

But Heine had hit on and gave voice to a significant tension — the growing antagonism between German culture and politics. The Napoleonic Code had inspired notions of universal humanism, but the “Teutomaniacs” (Prochnik’s term) sought to rein in such liberality. The parallels to American culture and current politics are startling — and in some of Prochnik’s summary paragraphs, one can hear him channeling Heine with a certain relish. He writes, “The persistent ugliness of the world, despite its glorious promise, is ultimately the fault of two groups of men: those who rile up the dumb brutes for a laugh, and the egoistic, deceitful monsters who heedlessly inflict their own misery on the rest of the universe, turning ignorance and suffering into a badge of honor that entitles them to make the world resound with the ghastly clamor of their humiliation, until nothing can be heard but a cacophony of idiotic, misdirected fury.”

Emancipation was the goal – and to achieve it, Heine looked towards a Weltvernichtungsidee or “a profound world-annihilating idea” to vanquish the plague of nationalistic tyranny. No wonder Nietzsche found in Heine “that divine malice without which I cannot imagine perfection.” In Paris, where Heine’s middle period began, he met Karl Marx. Heine’s prose writing expanded to include journalism and iconoclastic op-eds and articles on politics. (In Germany, he had produced The Harz Journey, an acutely observed and often satiric travel narrative, available today as Penguin Classic.) In 1854, he wrote “The Slave Ship,” noted as the first anti-racism poem in German.

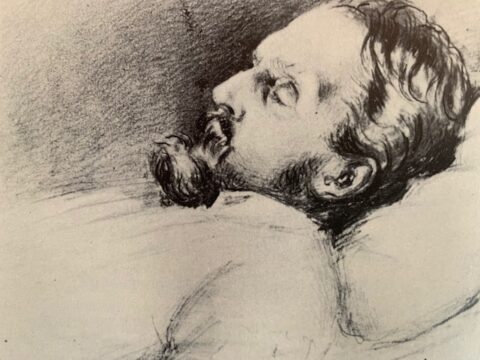

When he died on February 17, 1856, Heine was the most well-known, and for many the most notorious, practicing German writer, even if the French ultra-liberals found him too enamored of the salons. To the end, he wouldn’t give any of his antagonists a break. He wrote, “If God wants to make my happiness complete, he will grant me the joy of seeing six or seven of my enemies hanging … One must, it is true, forgive one’s enemies – but not before they have been hanged.” And as for God, Heine pronounced on his deathbed, “God will forgive me. It is his métier.”

When he died on February 17, 1856, Heine was the most well-known, and for many the most notorious, practicing German writer, even if the French ultra-liberals found him too enamored of the salons. To the end, he wouldn’t give any of his antagonists a break. He wrote, “If God wants to make my happiness complete, he will grant me the joy of seeing six or seven of my enemies hanging … One must, it is true, forgive one’s enemies – but not before they have been hanged.” And as for God, Heine pronounced on his deathbed, “God will forgive me. It is his métier.”

[Published by Yale University Press on November 245, 2020, 336 pages, $26.00 hardcover]