In a camp near Stuttgart, in the last months of the war, a man is approached by another man, old and hungry. Will he trade a stolen beet for the old man’s bread ration? The first man scoffs: no way can the old guy handle such rich food. But the hungry man insists. Resignedly, with contempt shaded by sympathy, the man makes the trade. And it happens just like he said: within hours the old man is incapacitated. He won’t make it to nightfall.

A woman, freed from the suffocation and despair of the cattle car she has been imprisoned in for days, lurches along the arrival ramp at Auschwitz. A little girl trails behind her, crying “Mama, Mama.” The woman walks faster, breaks into a trot, as if to outrun the pleading. “‘Sir, that’s not my child, sir, it’s not mine’,” she tells a sneering guard. Fueled on alcohol and cocoa powder, a prisoner conscripted into unloading the train knocks her down with a single blow, snatches her up, and strangles her before hurling her on to a truck of corpses. He throws the screaming child after her.

A woman, freed from the suffocation and despair of the cattle car she has been imprisoned in for days, lurches along the arrival ramp at Auschwitz. A little girl trails behind her, crying “Mama, Mama.” The woman walks faster, breaks into a trot, as if to outrun the pleading. “‘Sir, that’s not my child, sir, it’s not mine’,” she tells a sneering guard. Fueled on alcohol and cocoa powder, a prisoner conscripted into unloading the train knocks her down with a single blow, snatches her up, and strangles her before hurling her on to a truck of corpses. He throws the screaming child after her.

The inmates of a Displaced Persons camp capture a Nazi and hide him in a barrack while an American officer lectures them on the rule of law; later, “to the accompaniment of … heavy, hate-filled wheezing,” the inmates stomp their former persecutor to death.

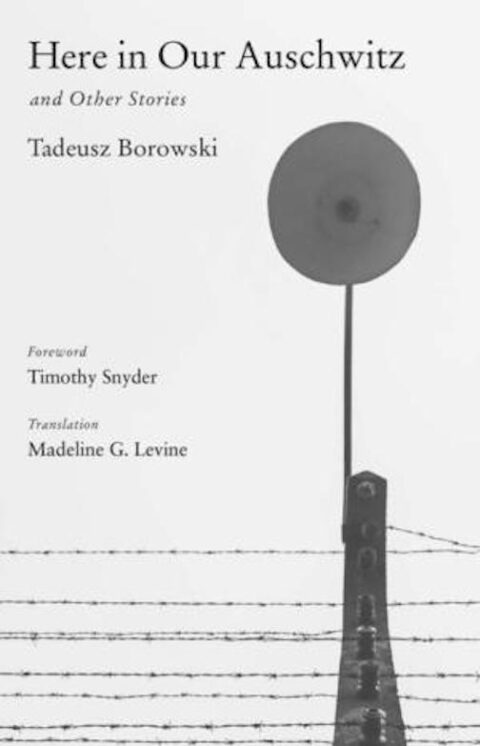

Taken from Here in Our Auschwitz and Other Stories, an invaluable collection of texts by the Polish writer Tadeusz Borowski and translated by the brilliant Madeline Levine, these harrowing scenes bear out the claim made by author’s alter ego, the voice that cynically and lovingly narrates these stories: “Human memory retains only images.” Such images, horrifying and indelible, leap from every page of the book. The women in the experimental medical block at Auschwitz I “stick their heads out through the bars just like my father’s rabbits.” The emptied buildings of the Warsaw Ghetto are fronted by “blank windows in which down from torn pillows and feather beds flutter[s].” An old woman eats a roll, chewing slowly to extend the pleasure of its soft whiteness; a man watching her catches sight of her rows of gold teeth, “instinctively calculating the weight and the value of the whole jaw.”

* * *

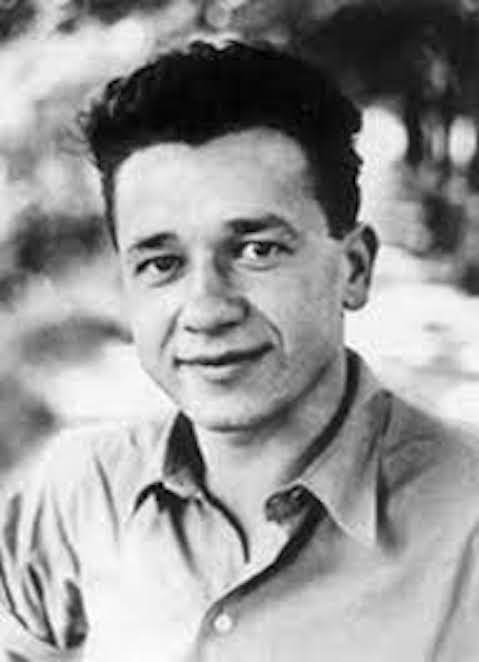

Borowski’s short, eventful life was shaped by the vicissitudes of 20th century totalitarianism. Born in 1922 to a Polish family in the newly-established Soviet republic of Ukraine, Borowski was still a small child when his father was arrested as an enemy of the people — his crime: working for an organization that had supported the Ukrainian government against the Red Army in 1920). Interned in a hard labor camp, Stanislaw Borowski toiled in bitter, primitive conditions to build a canal between the White and Baltic seas. Inmates often used spoons to do the work. Four years later, Borowski’s mother was sent to a similar camp in Siberia — her crime: being married to her husband. Borowski was taken in by an aunt, who kept him until Stanislaw was released to Poland as part of a prisoner swap in 1932. Two years later, Borowski’s mother was able to join them, and the family was reunited in Warsaw, where they lived a hard life, “proletarian at best” in the words of the historian Timothy Snyder, whose helpful introduction contextualizes the work.

Despite poverty and hunger, Borowski was able to finish high school in spring 1940, the final months in clandestine classrooms set up to resist German prohibitions on education. While working as a night watchman, he kept up his studies, attending underground seminars, writing poems, and reading constantly. Together with a fellow student, Maria Rundo, he also ran a side hustle distilling and dealing moonshine. Unlike Borowski, Maria was Jewish; but because her family had for centuries considered itself Polish, she and her parents ignored the order to move to the ghetto in the fall of 1940. Which explains why she was still living freely in Warsaw in early 1943, when almost all traces of Jewish life in the city had been extinguished. Maria was arrested in late February 1943 while arranging fake papers for a friend; Borowski, ignoring protocol and basic sense, went to find her. He was arrested, too. She burst into tears when she caught a glimpse of him at the infamous Pawiak prison. “Don’t worry,” he is reported to have said, “I wanted us to be together.”

They didn’t stay that way, but Borowski did everything he could to make contact with her. Both were sent to Auschwitz, Maria to the women’s camp at Birkenau (“luckily” for her she was designated a Polish communist rather than a Jew), Borowski to “old Auschwitz,” the original camp (a former Polish army barracks that the Germans repurposed as a concentration camp for Polish political prisoners in 1940). In late 1944, as the Germans began to dissolve Auschwitz, the couple was sent west in separate prisoner convoys, Maria to Ravensbruck and Borowski to Netzweller-Dautmergen, near Stuttgart, and eventually to Dachau, where he was liberated by American forces in May 1945.

In those first hallucinatory months after the war, Borowski’s only goal was to find Maria. Astonishingly, he managed to do it, but it would be another year before they were reunited. The lovers reluctantly returned to their homeland where Borowski became a functionary for the new Communist government. In those first years after the war, Borowski wrote the texts that made his name, the ones collected in this volume. Two had already been published in Munich in March 1946 in a collection written by three Polish camp survivors and bound in fabric from a camp uniform. Back in Poland, on his way to becoming an apparatchik, Borowski renounced his past work, declaring that he hadn’t been able to analyze his camp experiences in class terms, had “play[ed] around in narrow empiricism, in behaviorism, or whatever it’s called,” to the point that despite wanting to tell the truth he had “ended up in an objective alliance with fascist ideology.”

In those first hallucinatory months after the war, Borowski’s only goal was to find Maria. Astonishingly, he managed to do it, but it would be another year before they were reunited. The lovers reluctantly returned to their homeland where Borowski became a functionary for the new Communist government. In those first years after the war, Borowski wrote the texts that made his name, the ones collected in this volume. Two had already been published in Munich in March 1946 in a collection written by three Polish camp survivors and bound in fabric from a camp uniform. Back in Poland, on his way to becoming an apparatchik, Borowski renounced his past work, declaring that he hadn’t been able to analyze his camp experiences in class terms, had “play[ed] around in narrow empiricism, in behaviorism, or whatever it’s called,” to the point that despite wanting to tell the truth he had “ended up in an objective alliance with fascist ideology.”

This turn has always disappointed Borowski’s readers — to say nothing of the people who actually knew him. Snyder reports that Stanislaw Borowski — who had been interned in the Gulag, don’t forget, and thus knew what totalitarian regimes can do — begged his son not to repudiate his talent. Later, the poet Czesław Miłosz immortalized Borowski as a coward in his essay collection The Captive Mind. Snyder, by contrast, argues that Stalinism, with its ability to simply invent truth, was a desperate refuge for a writer who always felt trapped between his desire to contribute to European culture and his conviction that the tradition was tainted by violence and oppression.

Snyder similarly challenges the tendency to interpret Borowski’s life in light of his death. At the end of June 1951, Maria gave birth to their child. A week later, Borowski made his daily to the hospital before returning home to finish an article. He was found unconscious by the housekeeper the next morning. The gas had been left on; he had taken painkillers. Borowski died the next day. The verdict has usually been suicide, but Snyder and Levine (each has written an introduction to the collection) reject easy moralizing. Over the years many interpreters have taken perverse pleasure at the thought that a chronicler of Auschwitz, who repudiated his role as truth teller, would kill himself this way. Snyder rebuts this reading, noting that gas was the most common way of committing suicide in postwar Europe. Besides, nobody knows if he killed himself. Yes, Borowski was troubled in his last days. According to Maria, he had always been manic-depressive; perversely, only in Auschwitz had he been calm and collected, his lifelong courage there having a clear focus. He had tried to kill himself twice before. Moreover, at the time of his death, his personal life was a mess — but this fact, too, can be read ambivalently. His lover, Dżennt Połtorzycka, claimed his death was an accident: Borowski had been working late, put water on for tea, and simply fallen asleep. Why we are so desirous of linking Borowski to the gas that, as Levine observes, he was unlikely to have faced as a non-Jewish prisoner of the Nazis (his death would have taken some other form: disease, exhaustion, hunger, a bullet in the neck), so ready to ascribe to him survivor’s guilt, when that identity position had not yet gained currency? Borowski wasn’t even known as a Holocaust writer until he was translated to English in the 1960s, so keen were his contemporaries to see him as either a dupe of or a martyr to Stalinism.

* * *

In his writings, Borowski spared no one, least of all himself, since he believed that evil is constitutive of human being, not an aberration. In “Here in Our Auschwitz,” a text presented as a letter written by a man named Tadeusz to his girlfriend in another part of the camp — based on actual letters Borowski arranged to be smuggled to Maria — the narrator imagines himself being accused only of writing of depressing things. But he has to write the truth: “We are not conjuring up evil for no reason, irresponsibly; after all, we’re embedded in it.” The hardest thing to accept is how victims have become part of that evil, are even in complicated ways responsible for it, though of course not like perpetrators. Such complicity isn’t limited to the camps: “Look at what an original world we are living in: how few people there are in Europe who have not killed a man! And how few people there are whom other people would not wish to murder!” Borowski knew better than most that the camps were not a senseless detour in a history of forward-looking progress. They were intrinsic to the modern world, in which irrationality thrives despite the liberal consensus about its atavism. And he was honest enough to admit to irrationality’s appeal. Tadeusz speaks for his creator when, after bemoaning Europe’s terrible landscape of violence, he adds, in a bruising postscript, “I would like to slit one man’s throat and then another’s, so as to unburden myself of the camp complex, the complex of doffing one’s cap, of passively observing the beaten and the murdered, the complex of fear in the camp.”

That victims are merely put upon is one of many cherished beliefs Borowski sweeps aside in these stories — as well as the idea that terror is extraordinary. “The People Who Were Walking,” set in Birkenau in summer 1944 when tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews were gassed, exemplifies this terrible mundanity; the old prisoners simply have no time for these new victims: “The people in the camps had their own worries: they were waiting for parcels and letters from home; they were organizing for their friends and lovers, conspiring with other people.” The idea that liberation was an unalloyed blessing bestowed by uncorrupted heroes on some lamentable and morally suspect victims is similarly dispatched — the deportation camps that so many victims found themselves in after the war are a frustrating limbo: “Not quite concentration camp, not quite freedom.” Most provocatively and damaging to Borowski, as he negotiated the politics of newly Communist Poland, he denied that Poles suffered as much as Jews; Borowski never shied from Polish anti-Semitism: in a story set in occupied Warsaw, a working-class Pole tells the narrator about his day carting looted objects from the ghetto: “‘Pan Tadek, what I saw there, Pan Tadek, you wouldn’t believe. Children, women … it’s true, they’re Jewish, but still, you know’ …”

Even Borowski’s depiction of the most iconic Holocaust scene — the arrival of transports at Auschwitz — undoes expectations:

“The transport’s coming,” someone said, and everyone stood up expectantly … In its small, barred windows, we could see people’s faces, pale, crumpled, seemingly sleep-deprived — terrified women and men who, wonder of wonders, had hair. They moved past slowly, staring in silence at the station. Then something began seething inside the cars and pounding on the wooden walls.

“Water! Air!” Hollow, despairing cries erupted.

[…]

The bolts clanged; the cars were opened. A wave of air rushed inside, striking the people like poisonous fumes. Packed together beyond belief, crushed by the monstrous quantity of baggage, suitcases, large and small valises, knapsacks, bundles of all sorts… they’d been cooped up in horribly cramped conditions, they had fainted from the heat, died of suffocation, and suffocated others. Now they crowded around the open doors, breathing like fish cast on to sand.

This is from Borowski’s best known story, “Ladies and Gentlemen, Welcome to the Gas,” the very title enough to make you catch your breath. Barbara Vedder’s translation, until now the most widely available in English, calls it “This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen,” emphasizing the story’s horrific carnivalesque quality; Levine’s rendering, with its evocation of hospitality, might be even darker. The title refers to a scene in which an SS officer generates instant compliance from the terrified new arrivals by appealing to their better nature: “Meine Herrschaften, ladies and gentlemen, don’t throw your things around like that. You must show a little goodwill.” Contrary to its title, though, the story’s function is to show the reality behind strategically deployed deception.

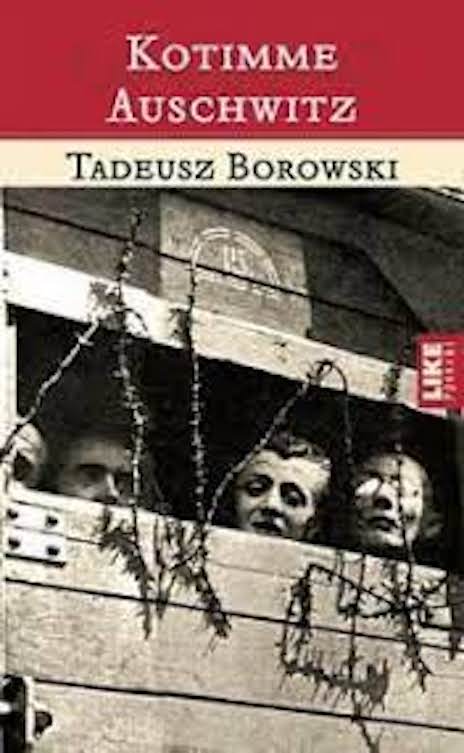

Borowski’s magnum opus disoriented readers because it is told not, as Holocaust texts so often are, from the point of view of those who are arriving at the camp, but from those ready to process them into a new and terrible life. We are outside the cattle car, not in it. The Polish narrator, able to receive packages and thus far more privileged than ordinary prisoners, is invited by his friend, the remarkably cynical and sententious Henri, a French Jew who has by unknown means amassed power, to join the Canada commando. In camp slang — what Borowski elsewhere called “crematorium Esperanto” — Canada referred to both the depot where goods plundered from new arrivals were stored before being sent to Berlin and, metonymically, the work detail, or commando, that did the taking. Valuables such as gold and currency were of course strictly forbidden to the prisoners, but SS men looked the other way when it came to food or linens or a pair of shoes, which the Canada men could “organize” for themselves. To work on the arrival ramp, was as lucrative as it was degrading. Borowski himself never performed such work, but is said to have arranged at some risk to himself to be able to witness it.

Borowski’s magnum opus disoriented readers because it is told not, as Holocaust texts so often are, from the point of view of those who are arriving at the camp, but from those ready to process them into a new and terrible life. We are outside the cattle car, not in it. The Polish narrator, able to receive packages and thus far more privileged than ordinary prisoners, is invited by his friend, the remarkably cynical and sententious Henri, a French Jew who has by unknown means amassed power, to join the Canada commando. In camp slang — what Borowski elsewhere called “crematorium Esperanto” — Canada referred to both the depot where goods plundered from new arrivals were stored before being sent to Berlin and, metonymically, the work detail, or commando, that did the taking. Valuables such as gold and currency were of course strictly forbidden to the prisoners, but SS men looked the other way when it came to food or linens or a pair of shoes, which the Canada men could “organize” for themselves. To work on the arrival ramp, was as lucrative as it was degrading. Borowski himself never performed such work, but is said to have arranged at some risk to himself to be able to witness it.

It is a classic narrative structure: an innocent enters a new world (his initiation allowing for readers’ enlightenment) and becomes experienced. The power of “Ladies and Gentlemen, Welcome to the Gas” comes from the perversity of the new world — the processing of transports of Jews at the ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau — and the sting of the realization that innocence and experience alike have taken on such terrible form. The narrator quickly learns that the work is physically and morally dirty. By the end he has forgotten all about the new shoes he was so excited to plunder, so destroyed is he after clearing rail cars of piles of excrement and the corpses of infants, tearing apart hysterical lovers, and lying in response to the incessant questions: Where are we? What will happen to us. (“It is the law of the camp that people going to their death are deceived until the final moment. It is the sole permissible form of pity.”) Before long, the narrator longs for the camp, seeing it now as an oasis in comparison to the hell of the ramp. He drinks, retches, tries to hide, and eventually falls into a fugue state, barely aware of the violence he’s perpetrating. In bewildered desperation, he asks Henri what’s happening to him:

“A totally inexplicable rage is rising inside me against these people… I don’t feel the least but sorry for them, that they’re headed to the gas… I could fling myself on them with my fists. But that’s probably pathological; I can’t understand it.”

“Oh, on the contrary, it’s normal, foreseen, and calculated. The ramp tortures you, you revolt and it’s easiest to unload your rage at those who are weaker.”

The passage indicts the narrator, the man who has become so complacent about it, and the system that enacts this violence (“it’s … calculated”) this violence. Eventually, the long day and night comes to an end: at least three transports bearing Jews from the ghettos of the Polish cities Sosnowiec-Będzin have passed through the commando’s hands. As a new day dawns — “a fine, hot day” — the Canada men return to the main camp, “loaded down with breads, marmalade, sugar, smelling of perfume and clean linen.”

Borowski’s stories are filled with parallelism that equates people with things — “An ordinary work day: trucks drive up, load up with lumber, cement, people” — but the point isn’t simply to show the camp as a place of dehumanization. It’s not just that people have been reduced to things, but that the very definition of what it means to be human is challenged.“Ladies and Gentlemen,” in particular, is a story about hierarchies. In its last lines, a detachment of SS men, braying stridently, come up behind the laden Canada men straggling to their barracks. The Canada men are ordered to the right. And the story ends with a whimper: “We make way for them.” Yet not every distinction is this stark. Even among the prisoners, regular shifts of fortune rule the day. “An envious justice reigns in the camp: when a powerful person falls, his friends strive to make him fall as low as possible.” But it’s not even the so-called privileged prisoners, like those on the Canada commando, who inhabit what Primo Levi famously called “the grey zone” of moral indeterminacy. The camp is a place of parasitism: it is designed to function that way; no one who lives and works in it escapes this law. The camps are other killing sites are typically depicted as damned places sealed off from the world; Borowski shows that they were in fact porous. People and goods traversed their borders — not as an exception, but by design. “Ladies and Gentlemen, Welcome to the Gas” argues that camp life, in the camps, meager as it is, cannot persist without that traffic. Perversely, Borowski’s most famous text tells a story of plenitude; the pages are peppered with lists of the goods commandeered on the ramp; the human effluvia is merely the devalued accompaniment to those objects. The camp is a place of insatiable consumption, where victims prey upon other victims. For me, the most resonant lines of the story are these:

The camp will live off this transport for several days: it will eat its hams and sausages, its preserves and fruit, it will drink its vodka and liqueurs, it will wear its linens, engage in trade with its gold and its bundles. … For several days the camp will talk about the Sosnowiec-Będzin transport. It was a good rich transport.

* * *

As someone who has taught the story so many times I practically have it memorized, I was amazed at the differences between this new translation and the one by Barbara Vedder, first published in 1967 and available as a Penguin Classic since the late 1970s. Levine’s version is simply stranger than Vedder’s. It’s also longer. I was shocked to see how much Vedder had omitted, sometimes phrases, but often whole sentences, at points entire paragraphs. Vedder’s cuts often concern specifics of camp geography; her Borowski lives in a much more generic concentration camp than Levine’s. Most egregiously, she cuts a long description in which the narrator imagines a landscape ruled over not by the four Birkenau crematoria but by sixteen such buildings, a camp so enormous it reaches to the Vistula, a Verbrecher-Stadt, a city of criminals, made up not just of Jews but also Poles and Russians, all of whom will burn, before being replaced by others from across the continent, in an endless procession that uncannily describes the Nazi plan to exterminate Slavs after the Final Solution was completed.

Borowski’s stories are shaped, to be sure — testimony is never simply neutral — but he is, deliberately, I suspect, a rough-hewn writer. At every turn, Vedder smoothes away that roughness. In the description of the transport’s arrival that I quoted earlier, for example, Vedder refers to “terror-stricken women with tangled hair, unshaven men” where Levine has “terrified woman and men who, wonder of wonders, had hair”: the latter equates the sexes and, by including the narrator’s surprise, emphasizes the distinction between what the old prisoners were and what they have become. The new arrivals have already been through horror. In Vedder, they “have fainted from heat, suffocated, crushed one another.” But in Levine, they “fainted from the heat, died of suffocation, and suffocated others.” Death is more prominent: something that has befallen some of the victims, but, chillingly, something they mete it out to each other. Vedder’s “crushed one another” sounds like they are packed to the gills; Levine’s “suffocated others” describes murder.) Later, describing the opening of the doors, Vedder says, “A wave of fresh air rushes inside the train,” while Levine adds a disquieting simile: “A wave of air rushed inside, striking the people like poisonous fumes.” Levine’s version is more bitterly ironic — gesturing to the poison of the gas chambers — and chimes with the simile that ends the passage, one that Borowski used in several of his stories, of the victims “breathing like fish cast onto sand”: that is to say, not breathing at all.

Borowski’s stories are shaped, to be sure — testimony is never simply neutral — but he is, deliberately, I suspect, a rough-hewn writer. At every turn, Vedder smoothes away that roughness. In the description of the transport’s arrival that I quoted earlier, for example, Vedder refers to “terror-stricken women with tangled hair, unshaven men” where Levine has “terrified woman and men who, wonder of wonders, had hair”: the latter equates the sexes and, by including the narrator’s surprise, emphasizes the distinction between what the old prisoners were and what they have become. The new arrivals have already been through horror. In Vedder, they “have fainted from heat, suffocated, crushed one another.” But in Levine, they “fainted from the heat, died of suffocation, and suffocated others.” Death is more prominent: something that has befallen some of the victims, but, chillingly, something they mete it out to each other. Vedder’s “crushed one another” sounds like they are packed to the gills; Levine’s “suffocated others” describes murder.) Later, describing the opening of the doors, Vedder says, “A wave of fresh air rushes inside the train,” while Levine adds a disquieting simile: “A wave of air rushed inside, striking the people like poisonous fumes.” Levine’s version is more bitterly ironic — gesturing to the poison of the gas chambers — and chimes with the simile that ends the passage, one that Borowski used in several of his stories, of the victims “breathing like fish cast onto sand”: that is to say, not breathing at all.

I don’t mean to cast shade on Vedder. Her translation introduced so many English speakers to Borowski; readers like me owe her. But Levine’s more comprehensive Borowski, with none of the jagged edges sanded down, will become definitive. I’m especially glad to have the complete text of The World of Stone — twenty short, sharp, bitter reminiscences of events Borowski experienced or witnessed during the war, only six of which appeared in the early translation. Levine’s Borowski is a properly Polish writer; Vedder’s was a writer of the Holocaust.

In “Here in Our Auschwitz,” after admitting to his girlfriend that he would like to kill people — “to slit one man’s throat and then another’s” — for he can imagine no other way of overcoming the complicity forced upon the inmates of the camp system, the narrator adds that this overcoming would be a terrible thing, a solution as bad as the crime it is meant to redress. No one who takes on this violent response to violence will come through it unharmed, but at the very least it might lead to truth: “I wish that some day we will be able to call things by their proper names, as courageous people do.” Only the truly courageous are able to look their own lack of courage in the face — their miserable, necessary, devastating cowardice, expressed as violence to others. As demonstrated by the pieces in Here in Our Auschwitz and Other Stories, Tadeusz Borowski, who told the stories of death by sugar beet, of the will to live so strong it disavows a child, of the brutal pleasure of revenge, courageously called things by their names, no matter how dark the implications.

[Published by Yale University Press on September 14, 2021, 392 pages, $28.00 hardcover]