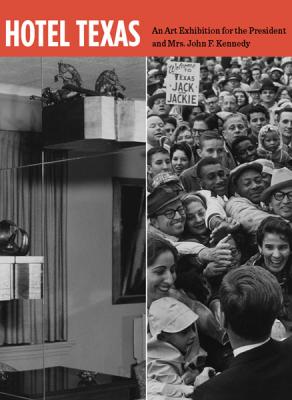

At 11:00 pm on November 21, 1963, Air Force One landed at Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth, Texas. A motorcade took President and Mrs. John Kennedy to the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth. Having only narrowly won the state’s electoral votes in 1960, Kennedy intended his visit to unite and motivate local Democrats in advance of the 1964 presidential race. Since the death of her prematurely born son that summer, Jacqueline Kennedy had avoided the public. News of her plans to accompany the President created a sensation and elevated the political significance of the moment.

On November 8, 1963, newspapers reported that Governor John Connally had requested the Fort Worth chamber of commerce to reserve 150 rooms in the Hotel Texas for the president’s visit. On Sunday, November 17, an art critic stringer for the Fort Worth Times named Owen Day read an article in the paper about JFK’s visit headlined “Suite Eight-Fifty … It’ll Be Famous.” But Day knew that suite 850 was hardly the hotel’s most luxurious unit. That distinction belonged to the Will Rogers suite on the thirteenth floor – assigned to Vice President Lyndon Johnson, son of Texas. On Monday the 18th, Day contacted an influential bank vice president and arts patron to propose fitting out the president’s drab three-room suite with art works from local museums and private collectors.

On November 8, 1963, newspapers reported that Governor John Connally had requested the Fort Worth chamber of commerce to reserve 150 rooms in the Hotel Texas for the president’s visit. On Sunday, November 17, an art critic stringer for the Fort Worth Times named Owen Day read an article in the paper about JFK’s visit headlined “Suite Eight-Fifty … It’ll Be Famous.” But Day knew that suite 850 was hardly the hotel’s most luxurious unit. That distinction belonged to the Will Rogers suite on the thirteenth floor – assigned to Vice President Lyndon Johnson, son of Texas. On Monday the 18th, Day contacted an influential bank vice president and arts patron to propose fitting out the president’s drab three-room suite with art works from local museums and private collectors.

Sixteen paintings and sculptures were quickly collected. Thomas Eakins’ Swimmers and Van Gogh’s Road With Peasant Shouldering a Spade were hung respectively over the headboards of the President’s and his wife’s beds (in separate bedrooms). The living area included Picasso’s sculpture Angry Owl and works by Claude Monet, Henry Moore, Raoul Dufy, Franz Kline, Marsden Hartley, Charles Marion Russell, Morris Graves, Eros Pellini and others. One hundred catalogs were produced entitled “An Art Exhibition for the President and Mrs. John Kennedy.”

When the exhausted Kennedys arrived after midnight, they disregarded the art. Jackie thought they must be reproductions – this was Texas after all. She ended up sleeping under the Eakins, he beneath the Van Gogh. The next morning, on returning to the rooms after an early event, Jackie discovered the catalog and realized what her hosts had arranged. The President’s final phone call was placed to Ruth Carter Johnson who had pulled strings to obtain, transport and hang the art. Ninety minutes later he was assassinated in Dallas. (Kennedy did not observe the art and examined the catalog only to find out who was responsible for it.)

When the exhausted Kennedys arrived after midnight, they disregarded the art. Jackie thought they must be reproductions – this was Texas after all. She ended up sleeping under the Eakins, he beneath the Van Gogh. The next morning, on returning to the rooms after an early event, Jackie discovered the catalog and realized what her hosts had arranged. The President’s final phone call was placed to Ruth Carter Johnson who had pulled strings to obtain, transport and hang the art. Ninety minutes later he was assassinated in Dallas. (Kennedy did not observe the art and examined the catalog only to find out who was responsible for it.)

Now, the Dallas Museum of Art and the city’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art are restaging the “Hotel Texas” exhibit (running through September 15 at the former and from October 12 to January 12, 2014 at the latter). Yale University Press has published Hotel Texas, a book that not only presents the art but documents the history and considers the significance of the restaging. Four essays by Olivier Meslay, Scott Grant Barker, David Lubin and Alexander Nemerov cover the angles.

Why has this exhibit been restaged? What binds together Claude Monet’s oil Portrait of the Artist’s Granddaughter (1876) and Franz Kline’s oil Study for Accent Grave (1954)? Oliver Mesley suggests that “to remember what took place at the Hotel Texas is to restore the memory of a Texas welcome that has been obscured by the assassination.” But Dallas was hardly united in a gracious and excited welcome for JFK. Warren Leslie’s intriguing 1964 book Dallas Private and Public still irritates people in Dallas for suggesting that the city’s ultraconservative psyche and strident right-wing politics had primed the skids for Kennedy’s murder. On the morning of the assassination, when Kennedy saw a full-page ad in The Morning News accusing him of pro-Communist actions, he turned to Jackie and said, “We’re really in ‘nut country’ now.”

Why has this exhibit been restaged? What binds together Claude Monet’s oil Portrait of the Artist’s Granddaughter (1876) and Franz Kline’s oil Study for Accent Grave (1954)? Oliver Mesley suggests that “to remember what took place at the Hotel Texas is to restore the memory of a Texas welcome that has been obscured by the assassination.” But Dallas was hardly united in a gracious and excited welcome for JFK. Warren Leslie’s intriguing 1964 book Dallas Private and Public still irritates people in Dallas for suggesting that the city’s ultraconservative psyche and strident right-wing politics had primed the skids for Kennedy’s murder. On the morning of the assassination, when Kennedy saw a full-page ad in The Morning News accusing him of pro-Communist actions, he turned to Jackie and said, “We’re really in ‘nut country’ now.”

But it is precisely because of Dallas’ lingering resentments and shames that Hotel Texas is so engrossing and why those interested in that moment in time may be drawn in. The ungraspable nature of the episode, the authority of the art versus the fleeting looks the Kennedy’s gave it on the way to the shooting, and then, the weightlessness of the art versus the dense reverberations of the assassination, the troubled motivations to restore the exhibit – all of this simmers in the book. With a touch of obsessiveness, Hotel Texas graphically illustrates where the works were placed in the rooms, and a chronology of events tracks the President’s trip.

But it is precisely because of Dallas’ lingering resentments and shames that Hotel Texas is so engrossing and why those interested in that moment in time may be drawn in. The ungraspable nature of the episode, the authority of the art versus the fleeting looks the Kennedy’s gave it on the way to the shooting, and then, the weightlessness of the art versus the dense reverberations of the assassination, the troubled motivations to restore the exhibit – all of this simmers in the book. With a touch of obsessiveness, Hotel Texas graphically illustrates where the works were placed in the rooms, and a chronology of events tracks the President’s trip.

Moving from fact to speculation, Hotel Texas culminates with Alexander Nemerov’s multi-vectored essay on the factors working against “the idea of meaningful connection” in the exhibit – followed by his thoughtful construction of various meaningful resonances. For starters, think of Eakins’ The Swimmers and Kennedy’s legendary long swim and survival in the South Pacific after the PT-109 was sunk by the Japanese.

In 1956, the Dallas Public Library attempted to mount an exhibit on Pablo Picasso and his career, but the city’s fathers objected to spending public funds on the work of a communist. Seven years later, a few affluent art lovers sympathetic to Kennedy’s presidency placed Picasso’s “Angry Owl” on his coffee table. He walked right by it. The rest of us may now consider the sculpture’s outraged aspect.

In 1956, the Dallas Public Library attempted to mount an exhibit on Pablo Picasso and his career, but the city’s fathers objected to spending public funds on the work of a communist. Seven years later, a few affluent art lovers sympathetic to Kennedy’s presidency placed Picasso’s “Angry Owl” on his coffee table. He walked right by it. The rest of us may now consider the sculpture’s outraged aspect.

[Published by Yale University Press on June 18, 2013. 112 pages, 120 color and b/w illustrations, $25.00 hardcover]

November 22

As a Texas writer, I remember that day with the same painful vividness as anyone who was alive at the time.

But I did not know that his last phone call was about the paintings. Whether he made the call just to thank those who arranged for the art or not, still: he valued it.

Kennedy and art

Kennedy’s speech at Amherst College is often invoked when there’s talk about his respect for art. But Kennedy’s attitude about art had more to do with the marketing of Jackie Kennedy and the halo effect on him. It was about the women’s vote. I’m not surprised that he didn’t pay attention to the art in his room.