Dahlia Ravikovitch once said that the value of a poet is worth less than that of a garlic peel. “A slice of bread with butter and honey on an oil cloth-covered breakfast table solves any problem better than an elusive poem,” she remarked in an interview. “What takes me out of the periods of depression that I occasionally succumb to is not poetry, but life. When it smiles at me, I can smile back.”

When Ravikovitch (1936-2005) won Israel’s most prestigious national honor in 1998, the Israel Prize, the judges’ citation noted, “Her poetic style is distinguished by its skillful synthesis of a rich literary language with the colloquial idiom, and of her personal outcry with that of the collective. This has made her the most important — indeed the most distinctive — Hebrew poet of our time. She is the central pillar of Hebrew lyric poetry.”

When Ravikovitch (1936-2005) won Israel’s most prestigious national honor in 1998, the Israel Prize, the judges’ citation noted, “Her poetic style is distinguished by its skillful synthesis of a rich literary language with the colloquial idiom, and of her personal outcry with that of the collective. This has made her the most important — indeed the most distinctive — Hebrew poet of our time. She is the central pillar of Hebrew lyric poetry.”

But Ravikovitch was a marginal poet, made so by her own ambition, temperament, technique, and the patrilineal habits of Hebrew poetry. Furthermore, her synthetic talents alone don’t account for her position as “the most distinctive poet” of Israel. The unique sound of her poetry resulted from an unresolved clash of tensions.

On the one hand, she like other contemporary Israeli poets took on the challenge of reinstating Hebrew, with its dense historical and cultural layers, as a language capable of expressing modernity. But also, to write in Hebrew, the rising language of statehood, implicitly expressed support for the cause — a language assertively turning outward.

On the other hand, Ravikovitch’s temperament accentuated her solitariness and suffered the difficulties of surviving the world. Her ambition was the wish for wisdom, or the sound of wisdom. Her poetic career was a confrontation with wisdom’s various voices – biblical or demotic, assertive or doubtful, satisfied or bitter, stable or imbalanced.

On the other hand, Ravikovitch’s temperament accentuated her solitariness and suffered the difficulties of surviving the world. Her ambition was the wish for wisdom, or the sound of wisdom. Her poetic career was a confrontation with wisdom’s various voices – biblical or demotic, assertive or doubtful, satisfied or bitter, stable or imbalanced.

She began publishing poetry in her late teens during compulsory service in the military. Her first book, The Love of an Orange, came out when she was just 23 in 1959. Its phrasing was classically arch, authoritative, allusive. By the 1980’s after a rather long poetic silence, her work could speak with restraint and precision.

THE WINDOW

So what did I manage to do?

Me – for years I did nothing.

Just looked out the window.

Raindrops soaked into the lawn,

year in, year out.

That lawn was soft grass, high class.

Blackbirds strolled across it.

Later, tiny flowers blossomed, fine strings of beads,

most likely in spring.

Later tulips,

English daffodils,

snapdragons,

nothing special.

Me – I didn’t do a thing.

Winter and simmer revolved among blades of grass.

I slept as much as possible.

That window was as big as it needed to be.

Whatever was needed

I saw in that window.

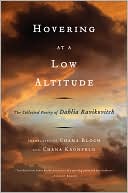

To move through Hovering At A Low Altitude is to follow Ravikovitch’s exquisitely painful trek through years of grief – and the victories of the poetry over circumstance. The poet is less than a garlic peel, but the poems are as tough as Golan tank commanders.

To move through Hovering At A Low Altitude is to follow Ravikovitch’s exquisitely painful trek through years of grief – and the victories of the poetry over circumstance. The poet is less than a garlic peel, but the poems are as tough as Golan tank commanders.

Perhaps the least benign influence on her work was the example of Anne Sexton. When the life peers at its image in the verse, when the emotion is static before the poem’s first word is spoken, Ravikovitch’s poetry loses much of its mysterious strangeness and treacherous depths.

But when she created a self from scratch on the page, memory would merge with archetype and literary tradition. Her favorite poem, “The Dress,” begins: “You know, she said, they made you a dress of fire. / Remember how Jason’s wife burned in her dress? / It was Medea, she said, Medea did that to her. / You’ve got to be careful, she said, / they made you a dress that glows like an ember, / that burns like coals of fire.” By the poem’s end, the “she” who warns has become yet another danger and the burning of the dress becomes inescapable, definitive. The final stanza: “But the dress, she said, the dress is on fire. / What are you saying, I shouted, what are you saying? / I’m not wearing a dress at all, can’t you see / what’s burning is me.”

Ravikovitch lived her life as a clinical depressive. She was married and divorced three times. She gave birth to her only child, her son Ido, when she was forty-four in 1978 and lost custody of him in 1989. She worked for a time as a journalist and a high school teacher. Cherishing her privacy, she refused to be interviewed for years until 1996 – which triggered a banner newspaper headline. She attempted suicide several times, and when she died of a heart attack, it was reported globally that she had taken her own life.

Ravikovitch lived her life as a clinical depressive. She was married and divorced three times. She gave birth to her only child, her son Ido, when she was forty-four in 1978 and lost custody of him in 1989. She worked for a time as a journalist and a high school teacher. Cherishing her privacy, she refused to be interviewed for years until 1996 – which triggered a banner newspaper headline. She attempted suicide several times, and when she died of a heart attack, it was reported globally that she had taken her own life.

FROM DAY TO NIGHT

Every day I rise from sleep again

as if for the last time.

I don’t know what awaits me,

perhaps it follows logically, then,

that nothing awaits me.

The spring on its way

is like the spring gone by.

I know about the month of May

but pay it no mind.

For me there’s no border between night and day,

just that night is colder

though silence is equal to them both.

At dawn I hear the voices of birds.

I fall asleep easily

out of affection for them.

The one who is dear to me is not here,

perhaps he simply is not.

I cross over from day to night

from day to day

like a feather

the bird doesn’t feel as it falls away.

The collection’s title is taken from a poem about the death of what is presumed to be a Palestinian girl. Ravikovitch spoke for years against injustice and wrote many poems in protest of Israeli military actions. In “Hovering at a Low Altitude,” the speaker (who is both engaged with the scene yet aloof from it, like the hovering of a helicopter) says, “I tuck my dress tight around my legs and hover / very close to the ground. / What ever was she thinking, that girl? / Wild to look at, unwashed.”

But Ravikovitch’s politics seem quite secondary to me as far as where the power issues in the art. She lived to construct a lyric identity of a person for whom the world is nearly impossible to endure. The “dress” tucked tightly here is the same burning dress told about above. The little Palestinian girl – what was she thinking? What was the 13-year old Ravikovitch thinking when she abandoned life with her mother in a kibbutz (too regimented, too much expected) and plunged headlong into a life she could barely negotiate?

“Power and powerlessness is Ravikovitch’s defining subject,” write Bloch and Kronfeld in their introduction, “the devastating consequences of unequal power relations for the individual and for society, the self in a state of crisis refracting the state of the nation.” Ravikovitch gave us a poetry of untenable positions – and thus through an amazing conversion of powerlessness into art, Hovering At A Low Altitude appears as nothing less than the quaking “central pillar” of Israeli life.

[Published by W.W. Norton on April 27, 2009, 270 pages, $29.95 cloth]