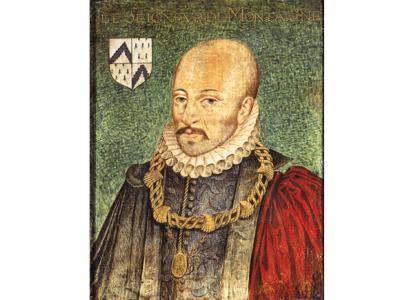

Michel de Montaigne was still revising his essays when he died at age fifty-nine in 1592. One of his favorite philosophers, the Skeptic physician Sextus Empiricus, had doubted whether anything is objectively knowable and preferred to suspend judgment. Revisions clarified and enlarged Montaigne’s perceptions while erasing narrow conclusions. An open question demanded a response: How to live?

“This is not the same as the ethical question, ‘How should one live?’” notes Sarah Bakewell. “Moral dilemmas interested Montaigne, but he was less interested in what people ought to do than in what they actually did. He wanted to know how to live a good life – meaning a correct or honourable life, but also a fully human, satisfying, flourishing one.”

What people actually did was frequently inhumane and mad. The civil war between French Catholics and Huguenots began with the Massacre of Vassy in 1562. The St. Bartholomew Day  massacres bloodied the Seine in 1572. There were plagues, poor harvests, starvation, and lawlessness. It was a time for picking sides, fearfulness, suspicion, and outrage. When Montaigne inherited his father’s estate in 1568, he decided to resign his position as magistrate in Bordeaux and return to his estate in Périgord. After a nervous breakdown and a riding accident that almost killed him, he was “liberated into light-heartedness … ‘Don’t worry about death’ became his most fundamental, most liberating answer to the question of how to live.” He began writing essays in the early 1570s; the first two books appeared in 1580 and enjoyed immediate popularity.

massacres bloodied the Seine in 1572. There were plagues, poor harvests, starvation, and lawlessness. It was a time for picking sides, fearfulness, suspicion, and outrage. When Montaigne inherited his father’s estate in 1568, he decided to resign his position as magistrate in Bordeaux and return to his estate in Périgord. After a nervous breakdown and a riding accident that almost killed him, he was “liberated into light-heartedness … ‘Don’t worry about death’ became his most fundamental, most liberating answer to the question of how to live.” He began writing essays in the early 1570s; the first two books appeared in 1580 and enjoyed immediate popularity.

For twenty years, he pursued his preferred subject – himself, which he described as “bashful, insolent; chaste, lustful; prating, silent, laborious, delicate; ingenious, inert; melancholic, pleasant; lying, true; knowing, ignorant; liberal, covetous, and prodigal.” His writing style was eccentrically discursive. Bakewell says, “ ‘Of Coaches’ begins by talking about authors, goes on to a bit about sneezing, and arrives at its supposed subject of coaches two pages later – only to race off again almost immediately and spend the rest of its time discussing the New World.”

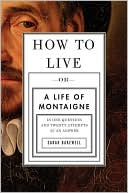

Bakewell preserves Montaigne’s darting spirit in her narrative, considering a multiplicity of topics relating to him while loosely following a chronology of his life. Some critics reasonably maintain “Who am I?” is Montaigne’s overarching inquiry. With “How to live?” as her armature, Bakewell conceives an ambitious structure based on Montaigne’s most favored implied behaviors. Each chapter answers “How to live?”: “Survive love and loss,” “Wake from the sleep of habit,” “Be ordinary and imperfect,” “Reflect on everything, regret nothing,” and so forth. But within the structure, Bakewell takes whimsical side trips, just as Montaigne was known to do during his travels to Italy and elsewhere.

Bakewell preserves Montaigne’s darting spirit in her narrative, considering a multiplicity of topics relating to him while loosely following a chronology of his life. Some critics reasonably maintain “Who am I?” is Montaigne’s overarching inquiry. With “How to live?” as her armature, Bakewell conceives an ambitious structure based on Montaigne’s most favored implied behaviors. Each chapter answers “How to live?”: “Survive love and loss,” “Wake from the sleep of habit,” “Be ordinary and imperfect,” “Reflect on everything, regret nothing,” and so forth. But within the structure, Bakewell takes whimsical side trips, just as Montaigne was known to do during his travels to Italy and elsewhere.

In chapter 12, “Guard your humanity,” Bakewell tells how the Catholic king Charles IX triggered the St. Batholomew’s Day slaughter of 10,000 Protestants. Montaigne’s family included believers on both sides, and he himself “paid little attention to theology.” Critical of torture and the rise of witch trials, Montaigne put himself at risk and earned the hatred of extremists on both sides who regarded him as a politique — a godless person “who paid attention only to political solutions, not to the state of their souls.”

This indirectly points to why How to Live resonates so powerfully as a most suitable narrative for our own moment in which political common ground has been eroded by ideologues and “apocalyptic imaginings.” As chapter 12 proceeds, Bakewell tells how Stefan Zweig, who first encountered (and was not taken with) the Essays in pre-World War I Vienna, later wrote an essay during his Brazilian exile on Montaigne’s “fight for interior freedom.”

Bakewell say s, “In a time such as that of the Second World War, or in civil-war France, Zweig writes, ordinary people’s lives are sacrificed to the obsessions of fanatics, so the question for any person of integrity becomes not so much ‘How do I survive?’ as ‘How do I remain fully human?’ … [Montaigne] thought that the solution to a world out of joint was for each person to get themselves back in joint: to learn ‘how to live,’ beginning with the art of keeping your feet on the ground.”

s, “In a time such as that of the Second World War, or in civil-war France, Zweig writes, ordinary people’s lives are sacrificed to the obsessions of fanatics, so the question for any person of integrity becomes not so much ‘How do I survive?’ as ‘How do I remain fully human?’ … [Montaigne] thought that the solution to a world out of joint was for each person to get themselves back in joint: to learn ‘how to live,’ beginning with the art of keeping your feet on the ground.”

In its casual, charming and rather shrewd way, How to Live tutors us on classical philosophy (since Montaigne plundered them for rhetorical models and material) and to trace Montaigne’s influence on writers who followed him (Pascal, Descartes, Rousseau, Nietzsche, Eliot. Leonard Woolf famously called him “the first completely modern man.” In his writings, Montaigne is sometimes an elusive and contradictory character. He has much to say about sex and penises, but rarely mentions his wife. He reflects long on civic life and the law, but has nothing to say about his years at court, parlement, or as mayor of Bordeaux. His modernity is heard in passages such as this:

“I have seen no more evident monstrosity and miracle in the world than myself. We become habituated to anything strange by use and time; but the more I frequent myself and know myself, the more my deformity astonishes me, and the less I understand myself.”

Horace, another of Montaigne’s favorites, had written in his epistle to Lucius Calpurnius Piso:

But oft our greatest errors take their rise

From our best views. I strive to be concise;

I prove obscure. My strength, my fire decays,

When in pursuit of elegance and ease.

Aiming at greatness, some to fustian soar;

Some in cold safety creep along the shore,

Too much afraid of storms; while he, who tries

With ever-varying wonders to surprise,

In the broad forest bids his dolphins play,

And paints his boars disporting in the sea.

Thus, injudicious, while one fault we shun,

Into its opposite extreme we run.

Montaigne would have admired these urbane notes of self-doubt. But his essays added to literature a completely new and idiosyncratic  sense of the world’s density. He then placed an implicit equals sign between his world’s strange phenomena and his solitary self – whether he was commenting on a public hanging, a circumcision, the griefs of short men, or playing with his dog. He advanced no arguments, developed no philosophy, proposed no novel notions about humankind, and sidestepped his religion’s preoccupation with salvation. Nevertheless, Sarah Bakewell’s splendid biography absorbs and expresses the timely force of Montaigne’s epiphany that, in her words, “enlightenment is something learned on your own body; it takes the form of things happening to you.”

sense of the world’s density. He then placed an implicit equals sign between his world’s strange phenomena and his solitary self – whether he was commenting on a public hanging, a circumcision, the griefs of short men, or playing with his dog. He advanced no arguments, developed no philosophy, proposed no novel notions about humankind, and sidestepped his religion’s preoccupation with salvation. Nevertheless, Sarah Bakewell’s splendid biography absorbs and expresses the timely force of Montaigne’s epiphany that, in her words, “enlightenment is something learned on your own body; it takes the form of things happening to you.”

[Published by Other Press on October 1, 2010. 400 pages, $25.00 hardcover]